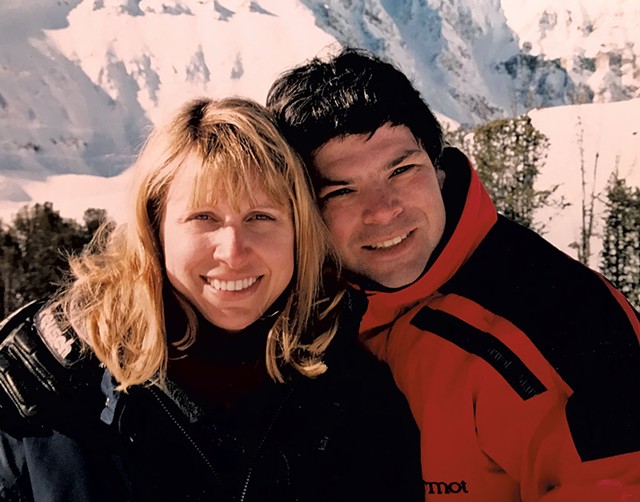

- Courtesy Of Randy Stern

- Randy Stern and his late wife, Annette Monachelli, on vacation in the 1990s

Even prescription drugs couldn't ease Annette Monachelli's headaches. Pain had plagued the 47-year-old inn operator for months when, on January 30, 2013, she came home from her second job as a server at Stowe Mountain Resort feeling worse still.

Her doctor had diagnosed the headaches as migraines, but this time her husband, Randy Stern, took her to the emergency room at Copley Hospital in Morrisville. There, doctors discovered a life-threatening brain hemorrhage. Despite emergency surgeries at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, she died the following week.

A brain scan could have detected the condition months earlier, Stern believed — if only Monachelli's doctor had thought to conduct one. But when he sued her doctor for malpractice in 2014, a startling e-document turned up: The physician had ordered a brain scan, Monachelli's electronic medical records showed. But the test was never administered.

The malpractice suit triggered a chain of investigations that stretched far beyond Stowe. In the years since, the United States Attorney's Office in Burlington has uncovered a pattern of corporate fraud among high-tech electronic medical record companies and recovered more than $350 million in settlements and criminal fines. These companies — once thought to be in the vanguard of health care — were really just cheats, the federal investigators say. Their flawed software put countless patients such as Monachelli at risk, the feds found.

That investigative trail led the office to discover a conspiracy of the highest order, U.S. Attorney Christina Nolan revealed last week. Practice Fusion, a former San Francisco Bay Area darling of the electronic medical records industry, hatched what she called an "abhorrent" deal with a pharmaceutical giant in 2016 to rig its software so doctors would prescribe more dangerous and addictive opioids. The company agreed to pay $145 million to avoid criminal prosecution.

Nolan's office has not named the drug maker, identified in charging documents only as "Pharma Co. X." But Seven Days last week used court documents to confirm that the deal described by prosecutors involved OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma, one of the most profitable companies in the U.S.

The investigation, also reported by Reuters, was revealed at a pivotal moment in the nationwide scramble to hold Purdue accountable for fueling an opioid epidemic. The State of Vermont has been merely one of thousands of state and municipal governments trying to extract a piece of Purdue's OxyContin fortune. Now, federal prosecutors in one of the smallest U.S. attorney's offices in the country could play a key role in determining how Purdue's opioid empire crumbles.

"We are committed to holding responsible actors accountable for this scheme," Nolan said, without explicitly confirming a continuing investigation into Pharma Co. X. "This is criminal conduct, and we're showing we can do this as a criminal case."

Although Purdue and Practice Fusion had nothing to do with Monachelli's death or the lawsuit it triggered, Nolan's team acknowledged that their alleged scheme might not have been discovered without it. "This all snowballed, in a way," said assistant U.S. attorney Owen Foster, who spearheaded the work.

Monachelli and Stern were New Yorkers who, like many Vermont transplants, had grown tired of urban life. Monachelli, a "very, very, very smart woman," Stern said, was a practicing attorney, but she quit her career in 1999 so the pair could take over the Gables Inn, a Stowe bed-and-breakfast. They ran it together for the next 13 years, skiing in their free time each winter.

In November 2012, Monachelli twice went to her primary care doctor complaining of unusual head pains that caused her to vomit. Each time, she was sent home with pain meds. After she died, Stern decided to sue the doctor for errors he believed had cut her life short.

Simple malpractice lawsuits don't typically involve the U.S. government, but Monachelli's doctor happened to work for a community clinic that qualified for federal liability protection. That meant Foster, a new assistant U.S. attorney with the District of Vermont, was tasked with defending the clinic. It was his first case as a federal lawyer.

Stern's chief claim was that his late wife's doctor had failed to "appreciate the need for immediate diagnostic imaging to determine if Ms. Monachelli was suffering due to an internal bleed or aneurysm," according to his 2014 complaint.

During Monachelli's second visit, however, her doctor wrote a note in the electronic medical file ordering a brain scan, court records show.

The clinic, like most around the country, had replaced its paper medical files with a computerized system that automated certain functions, such as conveying orders for diagnostic tests. Massachusetts-based eClinicalWorks, a company with $315 million in annual revenues, provided the system.

- Derek Brouwer

- From left: Michael Drescher, Christina Nolan and Owen Foster

To defend the clinic, Foster began to investigate why the brain scan wasn't carried out. Within months, he presented the court with a litany of customer complaints and civil lawsuits he'd collected about eClinicalWorks' software, including reports that it contained "dangerous errors" that "could result in patient death." A whistleblower lawsuit filed by former New York City IT employee Brendan Delaney charged that software glitches were affecting inmates at the city's Rikers Island prison. The 2011 lawsuit withered after the U.S. Department of Justice declined to sign on.

"We did not believe this was a case of doctor error," Foster recalled of Monachelli's death in an interview last week. "It looked like an issue of failed communication within the software."

Stern decided to settle his claims against the clinic in spring 2015, before Foster had finished his investigation into eClinicalWorks' software, leaving the question of its role in Monachelli's death unresolved. But Foster and the U.S. Attorney's Office soon revived Delaney's whistleblower case by moving it to Vermont.

"As things were summing up in our case," Stern said, "we started hearing that Owen Foster really thought there was something suspicious about the software ... We did not know it was going to turn into something as massive as it did."

Foster, who had no background in computer science or health care, led the investigation into eClinicalWorks over the next two years. In May 2017, federal prosecutors in Vermont announced the district's largest-ever financial recovery, a $155 million agreement with eClinicalWorks and several of its employees, to settle civil claims that they had violated the False Claims Act. The company did not admit wrongdoing.

eClinicalWorks was one of numerous tech companies trying to capitalize on a 2009 Great Recession-era federal stimulus package that paid health care providers to adopt electronic record keeping. Flaws in its software allegedly caused medication mix-ups and nearly 2,000 lab orders to go missing at Rikers Island.

Further, the software did not reliably record diagnostic imaging orders, like the one Monachelli's doctor had sought, prosecutors said.

Stern believes faulty software was a factor in his wife's death.

The eClinicalWorks case was the first of its kind, yielding Delaney, the New York whistleblower, a $30 million reward. The Justice Department later commended Foster as the "driving force" behind the case. The investigation was featured on the CBS series "Whistleblower" in 2018.

But the feds in Vermont weren't done. Investigators used their technical knowledge from the eClinicalWorks case to identify similar problems with other companies. In 2019, the U.S. Attorney's Office settled a second civil case involving Florida-based Greenway Health for $57 million.

"This is the new frontier in health care fraud," Nolan said in a press conference at the time. "That frontier is right here in our office."

Nolan's office won't say how many other companies are in its crosshairs. An investigation by Kaiser Health News and Fortune last year suggests prosecutors have only scratched the surface.

The report, which highlighted the Monachelli case, found that the $36 billion federal push to digitize records over the last decade "has created a host of largely unacknowledged patient safety risks."

"Our investigation found that alarming reports of patient deaths, serious injuries and near misses — thousands of them — tied to software glitches, user errors or other flaws have piled up, largely unseen, in various government-funded and private repositories," they wrote.

The Practice Fusion investigation was the first to establish that criminal behavior exists within the industry. The tech company provided its software to medical practitioners for free and sold advertising to reap profits. Sponsored alerts in the software suggested a course of action to doctors, based on information in the patient's file. Such alerts were legal, provided they followed established medical guidelines.

Practice Fusion's partnership with Purdue Pharma did not. Instead, it was a $1 million marketing project designed to boost opioid prescriptions even when they weren't appropriate, the government alleged. The software prompted doctors to regularly ask about their patients' pain and suggested extended-release opioids — of which OxyContin is a leading brand — as a treatment option.

"There's something sort of insidious about that, that this tool is being used for marketing agendas based on my personal health information," Foster said.

The alerts were triggered 230 million times nationally between 2016 and 2019. Practice Fusion's initial pitch estimated that the alert could yield 2,700 new patients for Purdue.

Nolan said providers who used Practice Fusion's software during that time prescribed more opioids than doctors who did not.

The criminal charges against Practice Fusion emerged from a civil fraud investigation into the company that mirrored those of Greenway and eClinicalWorks — the latest iteration in a series that was spurred by Monachelli's case.

"This is not like lightning striking once, twice. We are onto this," Nolan said at a January press conference, flanked by Foster and assistant U.S. attorney Michael Drescher. "The stakes are especially high when you're talking about opioids."

Purdue disclosed in a bankruptcy filing last fall that it faced federal civil and criminal probes. Its proposed $10 billion civil settlement with state attorneys general is contingent upon resolving the federal investigations, the filing stated. The company is in discussions with the government, Purdue said in a statement last week.

Stern, who recently sold the Stowe inn and moved to Waterbury, told Seven Days last week that he'd heard news of the Practice Fusion case on the radio and figured, "Boy, I bet Owen Foster's got something to do with this."

"God, it sounds like such a cliché. But when I do think about it," Stern continued, "at least I can say, 'Well, this one woman should not have died at 47 years old, but at least her death will go towards saving other people's lives."

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.