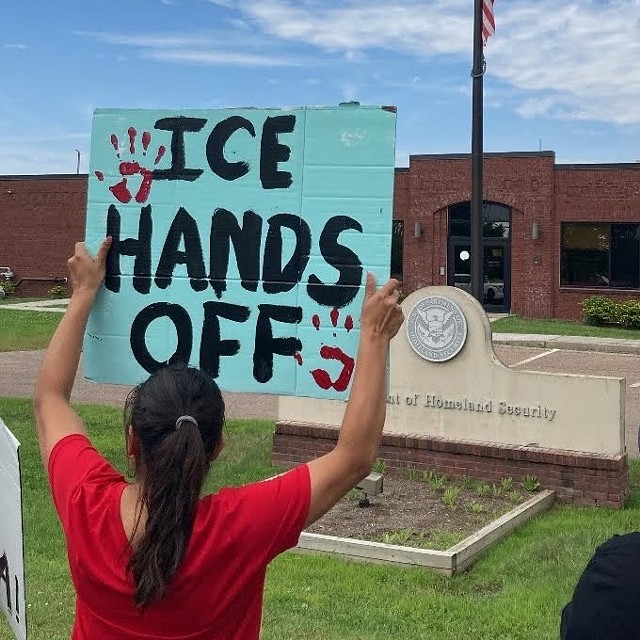

- Courtesy: Migrant Justice

- A protest on July 9 at the ICE office in St. Albans

Advocates say a woman from Honduras and her two children were deported from Vermont earlier this month after immigration officials failed to completely review the woman’s case for asylum.

Greisy Mejia’s case has been taken up by Brett Stokes, director of the Center for Justice Reform and assistant professor at Vermont Law & Graduate School, and Migrant Justice, a Burlington-based nonprofit that advocates for workers on local farms.

Mejia, 29, has actually been deported twice within the past eight months after fleeing Honduras over extortion threats in her home country. But both times, according to advocates, U.S. immigration officials did not review her claims that she feared for her life, which is part of the asylum process.

“They’re essential. It's not like you have an option if you express a fear. You must receive [a review],” Stokes said.

Mejia, her 9-year-old daughter and infant son surrendered to U.S. Border Patrol in Texas in November 2023 after illegally crossing the border and requesting asylum. But the federal agency, which, at the time, was dealing with a surge in illegal crossings and a backlog in asylum requests, sent her back to Honduras three days after she entered the U.S.

“She ought to have had a ‘credible fear’ review sometime in her crossing then, but it doesn't appear that that happened,” Stokes told Seven Days.

Mejia and her children fled Honduras again earlier this year and crossed the southern border in February. But they didn’t turn themselves in, according to Migrant Justice, and the family was kidnapped and held for ransom. Mejia finally escaped and contacted police in Uvalde, Texas. (Neither Migrant Justice nor Stokes provided more information about the kidnapping.)

Mejia and her children fled Honduras again earlier this year and crossed the southern border in February. But they didn’t turn themselves in, according to Migrant Justice, and the family was kidnapped and held for ransom. Mejia finally escaped and contacted police in Uvalde, Texas. (Neither Migrant Justice nor Stokes provided more information about the kidnapping.)

The family again found themselves in the custody of the U.S. Border Patrol, this time for about a month. According to Stokes, immigration services determined that Mejia was not a flight risk and allowed her to travel to Vermont, where her partner lives and works on a farm, under an order of supervision. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement gave her an ankle monitor and let her live in Vermont with routine check-ins.

“You could kind of think of it like parole or probation. You're just checking in with somebody to make sure that your address is still current and nothing's changed,” Stokes said.

Mejia connected with Stokes and the Center for Justice Reform in mid-June. The group planned on having her apply for a stay of removal, which postpones deportation, and a T visa, which allows victims of trafficking to stay in the U.S.

Stokes said Mejia had a routine check-in scheduled for July 22, and they were receiving positive signs about the situation. But very suddenly, according to Stokes, the agency moved up the meeting to July 9.

ICE records indicate Mejia was deported on July 10. Stokes said he first learned about it after Mejia called the Center for Justice Reform from Honduras. He has since filed her application for a T visa and is working to bring her back to the U.S.

“We denounce this cruel and horrific abuse,” Thelma Gómez, of Migrant Justice, said in a statement. “ICE needlessly and knowingly sent a family back to a country where their lives will be at risk — in violation of the law and the agency’s own guidelines. We hold ICE responsible for any harm that comes to Greisy and her family. This is an attack against the entire immigrant community.”

ICE, in a statement, said it followed proper procedures.

“A person who is ordered removed, is physically removed, and thereafter illegally reenters, can be subject to reinstatement of the previous removal order,” a spokesperson wrote in a statement to Seven Days.

Mejia’s deportation may be part of a trend of increased ICE enforcement, according to Stokes.

“From what I'm hearing from colleagues, the last six months or so is about as bad as [ICE arrests and removal operations have] been in recent memory,” he said.

Will Lambek of Migrant Justice also highlighted a similar case in 2020, when ICE deported Durvi Martinez from Vermont even though Martinez expressed fear for their life. Martinez, a farmer and activist, died of COVID-19 after being deported.

“[Greisy’s case is] not unprecedented, but this goes against the statutory obligations and ICE's internal guidelines,” Lambek said.

Greisy Mejia’s case has been taken up by Brett Stokes, director of the Center for Justice Reform and assistant professor at Vermont Law & Graduate School, and Migrant Justice, a Burlington-based nonprofit that advocates for workers on local farms.

Mejia, 29, has actually been deported twice within the past eight months after fleeing Honduras over extortion threats in her home country. But both times, according to advocates, U.S. immigration officials did not review her claims that she feared for her life, which is part of the asylum process.

“They’re essential. It's not like you have an option if you express a fear. You must receive [a review],” Stokes said.

Mejia, her 9-year-old daughter and infant son surrendered to U.S. Border Patrol in Texas in November 2023 after illegally crossing the border and requesting asylum. But the federal agency, which, at the time, was dealing with a surge in illegal crossings and a backlog in asylum requests, sent her back to Honduras three days after she entered the U.S.

“She ought to have had a ‘credible fear’ review sometime in her crossing then, but it doesn't appear that that happened,” Stokes told Seven Days.

- Courtesy of Migrant Justice

- Greisy Mejia and her daughter in Vermont

The family again found themselves in the custody of the U.S. Border Patrol, this time for about a month. According to Stokes, immigration services determined that Mejia was not a flight risk and allowed her to travel to Vermont, where her partner lives and works on a farm, under an order of supervision. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement gave her an ankle monitor and let her live in Vermont with routine check-ins.

“You could kind of think of it like parole or probation. You're just checking in with somebody to make sure that your address is still current and nothing's changed,” Stokes said.

Mejia connected with Stokes and the Center for Justice Reform in mid-June. The group planned on having her apply for a stay of removal, which postpones deportation, and a T visa, which allows victims of trafficking to stay in the U.S.

Stokes said Mejia had a routine check-in scheduled for July 22, and they were receiving positive signs about the situation. But very suddenly, according to Stokes, the agency moved up the meeting to July 9.

ICE records indicate Mejia was deported on July 10. Stokes said he first learned about it after Mejia called the Center for Justice Reform from Honduras. He has since filed her application for a T visa and is working to bring her back to the U.S.

“We denounce this cruel and horrific abuse,” Thelma Gómez, of Migrant Justice, said in a statement. “ICE needlessly and knowingly sent a family back to a country where their lives will be at risk — in violation of the law and the agency’s own guidelines. We hold ICE responsible for any harm that comes to Greisy and her family. This is an attack against the entire immigrant community.”

ICE, in a statement, said it followed proper procedures.

“A person who is ordered removed, is physically removed, and thereafter illegally reenters, can be subject to reinstatement of the previous removal order,” a spokesperson wrote in a statement to Seven Days.

Mejia’s deportation may be part of a trend of increased ICE enforcement, according to Stokes.

“From what I'm hearing from colleagues, the last six months or so is about as bad as [ICE arrests and removal operations have] been in recent memory,” he said.

Will Lambek of Migrant Justice also highlighted a similar case in 2020, when ICE deported Durvi Martinez from Vermont even though Martinez expressed fear for their life. Martinez, a farmer and activist, died of COVID-19 after being deported.

“[Greisy’s case is] not unprecedented, but this goes against the statutory obligations and ICE's internal guidelines,” Lambek said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.