- Trudy and Sandy Anderson

» Related story: How Vermonters have influenced IBM

Fifty years ago this month, IBM opened a plant in Essex Junction. The facility was filled with thousands of employees who produce microchips and . . . bonsai trees? Organic wines?

No, these commodities don't roll off the assembly line, but they are byproducts of Big Blue's presence in Vermont. In fact, if you scratch the surface of many of the area's attractions - the things that make the Burlington area a desirable place to live - you find some kind of connection to IBM.

Company spokesman Jeff Couture offers some of Big Blue's yearly stats as a way of illustrating its reach - payroll for 5700 employees: $350 million; IBM's contribution to the tax base: $6 million; its donations to local school and charities: roughly $2 million; its overall economic impact on Vermont: estimated at $1 billion. But these numbers don't reflect one of the biggest assets IBM has brought to the Champlain Valley: its people.

The Essex Junction plant has changed over the years. Its employees once made memory modules for IBM machines; today they produce microchips or semiconductors for cellphones and video-game systems. The company has always relied on a workforce that can design these components and turn them out. Manufacturing and hourly jobs have typically gone to locals. Some engineers and managers have come from the University of Vermont and state colleges, but Vermont's talent pool has never been big enough to satisfy IBM's demand. Over the years the company has imported many highly skilled professionals - people Couture describes as interested in "taking on a challenge and solving it."

The employees that IBM has brought to Vermont make more than microchips. Though many leave to further their careers or find warmer weather, a sizable number stick around. They start businesses, volunteer for nonprofits, and play a vital role in the schools. Over the years, they've populated Vermont's civic and political infrastructure. Their contributions have never been summarized on a balance sheet, but transplanted IBM employees have clearly affected the culture of this small state in important and often surprising ways.

Tiny Trees

Take Mill Brook Bonsai. Sandy Anderson opened Vermont's only tiny tree emporium in Jericho in 1997, the year he retired from IBM. Anderson, 64, came to the U.S. from Scotland in 1952, when he was 10. After studying engineering at Duchess Community College near Poughkeepsie, New York, he went to work at the nearby Fishkill plant. "I was in middle management," he says. "Logistics, planning and scheduling."

Anderson was later transferred to Manassas, Virginia. Then, in 1977, IBM sent him to Vermont; he and his wife, Trudy, bought a home in Jericho.

Anderson worked at IBM 12 to 14 hours a day, sometimes seven days a week, he recalls. Grooming bonsai trees helped him to unwind. "I used to come home from work and veg out on my trees," he says. "I don't want to sound all Zen, but I used to sit there and become one with my trees."

In 1983, he and Trudy became two of five founding members of the Green Mountain Bonsai Society. Twenty-four years later, the GMBS boasts a few dozen members and presents an annual show at the Champlain Valley Fairgrounds. Mill Brook Bonsai is the group's de facto HQ. Anderson hosts national bonsai experts, who give seminars on proper pruning.

Last year, Anderson chaired the Vermont Flower Show. He also served on the board of the Lake Champlain International Fishing Derby for several years, before his horticultural pursuits began to monopolize his time.

But he points out that, while he was working, his wife, Trudy, was far more involved in the community than he was. She volunteered as the public engagement coordinator for the Chittenden East Supervisory Union when the Andersons' three children were students. "I wrote newsletters, I helped teachers and school boards and district administrators communicate to parents and school boards. I helped them talk to people and facilitate meetings," Trudy says. She also wrote grants to IBM to receive donated computers. "Sandy worked at IBM long hours, and I was out in the world doing things," she notes.

Local Wine

In 1998, one-time chip-design engineer Ken Alberts launched Shelburne Vineyard, an organic winery.

Alberts, 68, is originally from New York City, and has an engineering degree from New York University. He joined IBM in 1964, transferring to Essex Junction in 1969 from Poughkeepsie. He began growing grapes in his Shelburne backyard three years later. At first he made only small batches of wine in 5-gallon buckets. In the mid-1990s, while traveling on assignment to an IBM plant in Québec, he realized his hobby had moneymaking potential. "I noticed there were these commercial wineries there," Alberts recalls. "And I said to myself, 'If they can do it in Québec, which is farther from the lake and colder than here, we can certainly do it here.'"

After Alberts retired in 1997, he secured a long-term lease on three acres at Shelburne Farms and established Shelburne Vineyard. Then he partnered with another resident with winemaking experience. In 1999, they leased land for a second planting on a nearby estate. A new winery and wine-tasting facility on 13 acres south of Shelburne Village is in the works for 2007.

Alberts doesn't find his transition from engineer to cold-climate winemaker odd. He speculates that a significant percentage of IBM engineers have an "adventurous spirit." In engineering, as in winemaking, he says, "You're sort of developing something that is kind of new, and the probability of success is definitely not 100 percent. You're willing to take a certain amount of risk."

Green Mountain Mosque

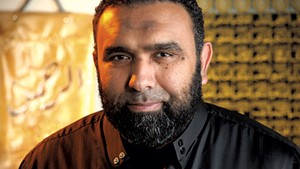

Amin Pothiawala, originally from Gujarat, India, came to Vermont from Connecticut in 1979. He and his wife raised their three children in Essex. Pothiawala, 58, started working as a independent techonology consultant when he retired from his senior engineering manager job at IBM in 2006. He also operates Pothiawala Enterprises, LLC. He rents trucks, finds clients in need of shipping, and recruits drivers - many of them job-seeking members of the Islamic Society of Vermont.

Pothiawala helped establish the ISV in 1995. He helped fundraise to buy the Colchester mosque. Muslim men are obligated to pray together on Friday afternoons. Before the ISV owned the mosque, they lacked a place of worship in this predominantly Christian state. "We started Friday prayer in my house," Pothiawala recalls.

Today Vermont's Muslim community is outgrowing the 5000-square-foot space. A great many of those who come to the mosque work at IBM and UVM; it's no coincidence the mosque is located halfway between the two, at Fort Ethan Allen.

But IBM is far from the only engine driving growth at the ISV. The influx of refugees from Muslim countries has also had an effect. Pothiawala says he and his wife collect bicycles and clothing for refugees, and often give them rides. "Refugees that come, they don't have anything," he says.

Kids' Friend in Court

Helping the less fortunate seems to be a popular pastime among IBMers; company spokesman Jeff Couture points out that the company and its workers contribute heavily each year to the United Way. They also volunteer their time. IBM retiree John Wilson of Hinesburg has chosen to pitch in through Vermont's guardian ad litem program.

Guardians ad litem are volunteer advocates assigned to children in the family court system. Wilson, an electrical engineer who retired in 1991, joined the program in 1993. "You have to work with the lawyers and the social workers, the teachers sometimes," the 65-year-old explains. "You get reports from doctors or schools. You attend case reviews and team meetings related to the child's situation. And talk to foster parents, and visit homes."

He's worked with lots of kids in 14 years. "I carry a caseload of around 25," Wilson says. "I've had some kids for 10 years. I've never tried to add up the number I've had, but it's got to be easily 150 or more."

Wilson says two other former IBMers have also become involved in the guardian ad litem program. "Engineers are problem solvers," he says. "That's the way I look at the job. These kids have problems. What's in their best interest, and how do you solve it? What resources do you use? There are a lot of professionals you deal with who are paid to solve those problems and, as a volunteer, you don't have to solve them yourself. But mustering resources or making the communication is sometimes critical to getting the problem solved."

Wilson says he might not have come to Vermont if he hadn't gotten the job at IBM - he's originally from a small town in Kansas called Cherryvale. He and his wife moved here in 1969, after he graduated from Northwestern; she got hired at UVM and later founded an educational software company.

"Vermont just happened to have two jobs, and we bit," Wilson says. "I can't say we knew a whole lot about Vermont before we came, but we think it's the best base of operations you could ever get now."

Relief from Abuse

South Burlington resident Mary Alice Schatzle, 49, has a similar story. She grew up in Cold Spring, New York, across the Hudson River from West Point, and was among the first computer-science majors at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. When she graduated in 1979, "the world was kind of my oyster," she says. "I had lots of job offers."

It came down to a choice between working for Honeywell in Arizona, and IBM in Essex Junction. She thought the Burlington area sounded like fun, and it wasn't as far from home. Twenty-seven years later, Schatzle is still at IBM, working as a "computer architect in the integrated supply chain organization." In other words, she works with software that helps the company determine which products to build in which facilities. She received her Master's degree in computer science from UVM in 1986.

From 1987 until 2000, Schatzle volunteered with Women Helping Battered Women. For the first few years, she had a weekly shift in their family shelter, and later served as an officer on the steering committee. "I think it's important for people to give back to their community," she says.

In 1997, Schatzle became a founding board member of the Samara Foundation, whose mission is to raise money to support Vermont's gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender population. Samara gives scholarships to high school students. Past grant recipients have included the AIDS Project of Southern Vermont and Transgender Day of Remembrance. She served until 2002, and recently returned to the board. Schatzle came out as a lesbian after moving to Vermont, and was one of the founding members of IBM's national gay and lesbian diversity task force.

There weren't many white-collar women at IBM when she arrived, she says. In her 200-person unit, there was only one other professional woman, she says. "All of the others were local women who were hourly employees." The percentage has changed, but the field is still dominated by men. "Semiconducting and manufacturing is a nerdy kind of business," Schatzle admits. "It attracts physicists. It's just not always a realm that attracts women."

MS Support

Some IBMers have helped found groups that fill a community need in Vermont. Bill Boyce of Underhill says he didn't exactly start the Chittenden County multiple sclerosis support group he's been facilitating for the past 15 years, but he was essentially its first leader.

Boyce got involved with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society after his wife, JoAnn, was diagnosed with the disease in the 1982. At the second meeting of the support group, the man leading it told the participants he would no longer be attending. "I said, 'You're not going to lead us anymore? Then get the hell out,'" Boyce remembers. "Then everybody looked at me and said, 'You'd be a good leader.' That's how it all started."

Boyce, a native of Dayton, New Jersey, started at IBM as an entry-level manufacturing operator on the night shift and later became a manager in the semiconductor development lab. He moved from New Jersey to Virginia, then here in 1978. He retired in 2001.

"I didn't want anything to do with this place at all," Boyce says of Vermont. "All I knew was that it was very cold. Eskimos and all that. But they told me that if I moved, they would let me manage the department."

Boyce has adapted to the cold climate and is an active outdoorsman. He volunteers as a hunting-safety instructor, and in 2000 was named Vermont's hunting instructor of the year.

Disabilities Advocacy

Like Boyce, Paul Betz of Cambridge was spurred to action by a disabled family member - his son was born with cerebral palsy in the 1970s. Betz helped start a Vermont chapter of United Cerebral Palsy.

Now 61, Betz moved here in 1970 from Rochester, New York, to take a job as a quality engineer at IBM. His wife was from Enosburg; she died the year Betz retired, in 2001.

Betz says he helped start the CP group because every year United Cerebral Palsy had a telethon and all of Vermont's contributions would go to the nearest chapter, in the Boston area. "We got a parents' group together," he recalls. "There were probably 10 or 12 couples, all of whom had kids who had been diagnosed with CP."

In 1979, Betz was appointed vice chair of the governor's Developmental Disabilities Council; he served until 1984.

These days he works as a substitute teacher three days a week at the Hyde Park Elementary School, where he sees himself as an unofficial mentor to some of his kids. "I love it," Betz says.

Holocaust Awareness

Other former IBMers have enjoyed a second career in Vermont schools as well. Gabe Hartstein of Burlington retired in 2001 and now teaches algebra at the Community College of Vermont. The 70-year-old native of Hungary, a Holocaust survivor, also volunteers to speak to younger Vermont students about his experiences during World War II. For the past 13 years, he's visited between five and 10 schools annually to tell how he evaded the Nazis. His family fled Budapest thanks to Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat who helped thousands of Jews leave Hungary and escape the concentration camps. Hartstein says students now know about the Holocaust, but it remains a distant event to them. "They are interested in meeting a survivor," he says.

Hartstein moved to New York City in 1955, and received a Master's degree in physics from NYU. For eight years he tried to get hired at IBM. "I really wanted to be in Fishkill," he says, "but I got in in Vermont in 1978. I grabbed it."

Suburban Planning

Transplanted IBMers have also influenced the civic and political culture of Vermont. In addition to owning the Shelburne Vineyard, for example, Ken Alberts has spent a decade on Shelburne's planning commission, and 18 years on the selectboard. John Dinklage has a similarly lengthy record of service in South Burlington.

The retired semiconductor engineer moved to Vermont in 1968. He came from the Fishkill plant, but is originally from Kansas City, Missouri. Dinklage was on the South Burlington City Council for nine years, the zoning board of adjustment for seven, and also for the past seven years has chaired South Burlington's busy development review board.

"Everything that happens passes through this board," Dinklage says. "South Burlington has come into its own as more than just a suburb of Burlington."

Dinklage also points out that his wife, Alida, has been very active in the community, too. She's volunteered at the Flynn Center and served on its board, been on the Vermont Symphony Orchestra's education committee, and volunteered in South Burlington schools. Today you can find her volunteering as a docent at Burlington's ECHO Center.

Progressive Banking

If you saw Richard Kemp, 74, at a protest or a political rally, you'd probably never guess that he once worked in human resources at IBM. Kemp transferred to Essex Junction from Westchester, New York, in 1968; he retired in 1983. Since coming to Vermont, the African-American activist has served on the board of the Peace and Justice Center, the Shelburne Craft School, the Vermont Community Loan Fund and CCTV, which produces "Near and Far," his interview program on public access channel 17.

Kemp is a member of the Progressive Party - though in 1984 he was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, when Jesse Jackson ran for president. Kemp sits on state and city Progressive Party committees. He's run for the state legislature and justice of the peace in the past, and served two years as Ward 5's Burlington City Council rep, from 2001 to 2003.

Kemp has also worked with Burlington's Sister City committee for Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, and has coordinated the Vermont Committee on Southern Africa. Over the past decade, he's helped send two tons of textbooks from the UVM Medical School to a university in Ghana.

Kemp's latest project is establishing a micro-bank in Malawi with $7000 in donations, mainly from Burlington's Unitarian Universalist Society and City Market. The Foundation for International Community Assistance in Washington, D.C., will run the bank, based on the model popularized by 2006 Nobel Peace Prize winner Mohammed Yunus. It will make small-business loans to poor people, mainly women, who would otherwise have little access to capital.

"I have become a progressive industrial banker," Kemp says with a chuckle. "That's dynamite. Absolutely dynamite." He's working on a second bank, in Haiti.

Kemp concedes that his progressive causes might sometimes seem at odds with his former job at a multinational corporation, but he has fond memories of IBM. "It was kind of a fun job," he says. "It paid quite well . . . and it had enormous health benefits for children and spouses." Kemp has six children, four of whom still live in Vermont, along with several of his 13 grandchildren.

"It was a great deal," Kemp says of his time at IBM. "I enjoyed working there."

Big Blue in the Face

Vermont's IBMers take center stage on the company's national labor struggles

By Ken Picard

Earl Mongeon admits that he wasn't comfortable speaking before large groups of people in the past. But as an IBM employee in Essex Junction for more than 25 years, he was one of the thousands of IBMers who lost a big chunk of money in 1999 when the company switched from its traditional pension plan to a cash-balance pension plan.

n response, Mongeon mustered up the courage at IBM's 2002 shareholders' meeting in Savannah, Georgia, to confront then-CEO Louis Gerstner face to face. Standing at the microphone in front of several thousand people, Mongeon pointed out to his top boss that while the value of his own pension was being slashed by 47 percent, when Gerstner retired he would receive $1.1 million in severance pay and 100 percent medical coverage for him and his family.

"As soon as I made that statement, my microphone was shut off," Mongeon recalls. "You want to talk intimidation? I was just shaking."

These days, Mongeon sounds a very different tune when he describes speaking his mind to the bigwigs at Big Blue. As vice president of the Alliance@IBM, a nationwide "local" of several thousand IBM employees across the United States, Mongeon has been willing to go to the mat on behalf of his fellow employees, whether to secure medical benefits for retirees, advocate for safer working conditions in the manufacturing facilities, or advise workers about age-discrimination lawsuits and elevated cancer rates.

Mongeon, who succeeded former Alliance VP Ralph Montefusco of Burlington in 2005, is just one of the dozens of Vermont-based IBMers who have consistently made their voices heard by the global high-tech giant. While IBM employees have had a dramatic impact on Vermont's culture (see accompanying story), Vermonters have also affected the culture at IBM. In fact, since the union's formation in 1999, state residents have consistently held leadership roles and been actively involved in shareholder initiatives, including one - which has received shareholder support year after year - that would cap executive compensation.

The Alliance is somewhat different from traditional unions in that it's not officially recognized by management and is not yet able to collectively bargain on behalf of its members. Also, unlike other unions, the Alliance's membership is open to all IBM employees, regardless of the type of work they do for the company.

Why have Vermonters played such a central role in the union? Alliance President Linda Guyer, who works at the IBM facility in Endicott, N.Y., offers an interesting theory. "If you go through all those cold winters, you've got to have a lot of chutzpah," she says with a laugh.

"In certain places, we have passionate people who don't mind being public," she continues. "A lot of people are very afraid of being treated badly, or being fired or intimidated for being in a union. Not in Vermont."

One theory about why Vermonters have been so active has to do with the union's history, Mongeon suggests. In 1999, when IBM made changes to the company's pension plan, then-Congressman Bernie Sanders hosted a town meeting on the controversy. More than 1000 affected IBM employees and family members attended.

"It went all across socioeconomic boundaries, whether you were an engineer or a manufacturing worker or a manager," Mongeon recalls. "Everybody was affected. The anger was running really high.

"Most Vermonters are hardworking and have a good work ethic," he adds, "but we don't like to be taken advantage of."

These days, the Alliance's role is growing, as IBM shifts from its traditionally large, centralized facilities to more remote worksites. According to Guyer, about 40 percent of IBM employees in the United States now work from home. Alliance organizing happens largely online; each month, www.allianceibm.org gets more than 30,000 hits. (The union has only two paid employees). Apparently, the union is perceived as a threat - the company blocks Alliance@IBM email messages from being delivered to its employees.

For his part, Mongeon isn't surprised that Vermonters are so integral to the union; it's simply a reflection of their community activism in general, and their historical role within the company. "This plant in Burlington is one of the stalwart plants," he says. "It's always come through when IBM needed it."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.