- File: Luke Awtry

- Alex Hazzard and Evan Litwin

Most everyone in the Zoom room for the Vermont Board of Libraries meeting agreed it was a good idea to change the name of Negro Brook in Townshend. Days earlier, Texas — Texas — had successfully replaced more than a dozen place names containing "Negro" with ones that honor notable Black figures.

Yet an hours-long hearing last Thursday to do the same for the obscure waterway in southern Vermont managed only to leave most participants feeling offended or misunderstood.

The bitter conclusion was not entirely unexpected. The campaign had become contentious soon after Burlington residents Evan Litwin and Alex Hazzard started the Rename Negro Brook Alliance in 2019. Their single-minded approach had alienated some locals in Townshend. Their relationship with State Librarian Jason Broughton, the first Black person to hold that post in Vermont, was also strained.

Activists had gathered more than 25 signatures on a petition and proposed a new name: Susanna Toby Brook, in honor of a 19th-century Black resident of the area, Susanna Toby Huzzy, whose story was unearthed by Vermont historian Elise Guyette.

But questions lingered about whether her name was most appropriate for that place, and whether her last names, Toby and Huzzy — the name Susanna lived by while in Townshend — could be offensive to some. At a hearing last December, Broughton, who advises the library board on geographic naming, had expressed further concern that the activists had sown "discord" rather than build unity around their petition. Broughton said he personally did not think the word "Negro" was racist and alluded — obliquely — to problems with their proposed replacement — "Toby." He urged them to abandon their petition and start over.

The activists pushed forward anyway. In a message to supporters days after the December hearing, alliance leaders wrote that they were "shocked and disturbed" by library board members' comments and vowed to combat "misogynistic behavior" that is "rooted in unconscious bias against those who support our efforts, our research, and Susanna Toby/Huzzy herself."

More than 50 people were in the virtual meeting room last week when Litwin took the floor at the start of a second hearing before the library board.

"I did want to just say," Litwin began, his goateed face framed between two tall houseplants, "that the land that we're discussing today ... is the unceded territory and traditional homeland of the Elnu band of the Abenaki." He announced that the Elnu band had endorsed their proposed name change.

Litwin next cited the breaking news out of Texas. State lawmakers there had first tried to change the names in the 1990s, he explained, but the federal board with final authority over geographic place names had rejected the request, citing too little evidence of local support.

"When asked what new evidence changed the mind of the federal board," Litwin said, citing national news reports, "a member of that board said the new evidence is that that was 1998 and this is 2021." The same board would need to approve any name change in Vermont, too.

As Litwin prepared to pass the floor to his partners, Hazzard and Guyette, a library board member interjected. "I was just curious," said James Saunders of Plainfield, an emeritus professor of Black literature at Purdue University. "The United Negro College Fund, should that be changed, too, do you think?"

"I don't see, personally, how that is relevant to my petition," responded Litwin, who is white. "They are a widely respected organization that have the right to keep or change their name. What the United Negro College Fund is not is public land on a map that everyone has to physically interact with."

Broughton, the state librarian, jumped in, speaking through a large headset. "Do the three of you still maintain that the word 'Negro' is 'racist, offensive and oppressive?'" he asked, quoting an earlier statement by the alliance.

"Me personally, as a Black person, I do find the word Negro offensive," Hazzard said.

The alliance had not won the support of the Townshend Selectboard, which instead voted to hold a town-wide vote on the topic in 2022. The Townshend Historical Society initially put forward a competing new name — Freedom Brook — but withdrew it and remained neutral on the Susanna Toby petition.

In April, Hazzard explained, the alliance held a meeting for people who lived in and around Townshend. The meeting included an "affinity space" for Black, Indigenous and people of color. BIPOC attendees, Hazzard relayed, agreed that the name should be changed but did not think the new name should reference "white saviorhood" or slavery.

Bruce Post, the white library board chair, asked Hazzard what he meant by white saviorhood. Hazzard said, as an example, that it would be inappropriate to rename the brook in reference to the Underground Railroad, because doing so would focus on "white folks saving Black folks from slavery." Litwin nodded in agreement.

Post then quoted a months-earlier statement by Litwin describing the Townshend Historical Society's proposal of Freedom Brook as "polite racism."

"I found it, actually, offensive," Post said. "You were charging the individuals with racism ... It is not something that brings people together. It drives them apart."

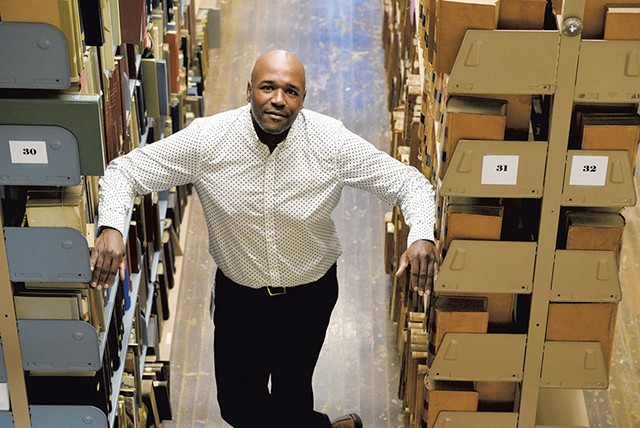

Post handed the floor to librarian Broughton, who appeared by video from his office.

- File: Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Jason Broughton

Broughton let out a deep sigh. "My plan today is going to be to discuss with you what conversations have occurred between myself, Alex Hazzard, Evan Litwin ... and Dr. Elise Guyette," he said. "Some of this will be a bit surprising."

Broughton said the alliance is "doing an admirable thing" and that he wanted to help their effort be successful.

He then started a long, detailed timeline of their interactions.

"I must say," he warned, "it has not been an easy conversation."

In early stages, Broughton explained that he had urged Litwin to seek the support of people in Townshend — not because the brook is theirs to name, but because it's important to have a "unifying petition." Litwin, in turn, declined meetings with Broughton, pledged to muster political pressure from the NAACP and former state representative Kiah Morris, and filed records requests with Broughton's office, the state librarian said.

The activists "finally" agreed to a meeting on July 23, 2020, Broughton said.

During that meeting, Broughton said, the alliance leaders explained why they had not included Susanna Toby Huzzy's surname, Huzzy, in their proposed name. Huzzy, they believed, sounded too similar to "hussy," a pejorative term for a promiscuous woman.

But Broughton said he relayed to them his own observation that, growing up in the South, he knew "Toby" to be a racial slur against Black people.

"At that point, what is quite startling is, I was told I should not feel the way I feel," Broughton said. "That was quite unique because the optics of this were not necessarily good."

Broughton looked off-screen, his fist to his mouth. After a pause, he turned back to the web camera and spoke directly to Guyette, the white historian who authored Discovering Black Vermont: African American Farmers in Hinesburgh, 1790-1890. Broughton said he'd asked her, during the meeting, to pass along her research on Toby Huzzy for review.

"The question that you asked me," Broughton said, "and I took this personal, and I'm saying this on the record. It has no merit for the board to consider, but it's just me. I've always wanted to ask you, why did you ask the question to me this way in front of my staff, and Evan and Alex: 'What and who gives you the right to critique my work?'"

"I will never forget that," he said.

Guyette turned on her web camera. "May I speak at this moment?"

"I would not like you to do so at this moment ... There is still quite a lot more," Broughton said.

Ten minutes later, Guyette got her chance to respond. "I am not a disrespectful person. I would never have said that," she insisted.

She continued, speaking to Broughton: "I'm just totally flabbergasted by what you have accused me of doing ... It's so hard to prove a negative, but that didn't happen."

"I have witnesses," Broughton replied.

"Time-out!" Post, the library board chair, interrupted.

Post then popped another surprise. He unveiled a slideshow presentation of his own research into the racial history of "Toby," including newspaper clippings from the 1980s and a recent discrimination case in Canada in which a former prison guard was awarded $964,000 in damages for, in part, being called the word by his coworkers. The slur is a reference to the character in the 1976 book Roots, Kunta Kinte, who was renamed Toby by a slaveholder. The slaveholder later cut off half of Kinte's foot to stop his escape attempts.

"If Huzzy was considered offensive and unusable, I don't see why Toby should be given a pass," Post said, "especially when, out of his lived experience, the state librarian told me about how it was used when he was growing up."

Litwin, Hazzard and Guyette maintained that they hadn't discounted Broughton's personal experience. "I remember personally acknowledging the experiences that Commissioner Broughton had," Litwin said. "The conversation we had around that, I thought, was rich. I thought we all had the same understanding."

Another library board member, Tom Frank of Milton, said Huzzy would have been a fine choice, phonetic connotations aside. "If people are offended, then you do education," he said. But the board did not have the ability to edit the proposed name. To tweak the proposed name, the alliance would need to start the whole process over again, signature-gathering and all.

"I'm really sorry that this has become so adversarial and contentious," added library board member Maxie Ewins. "I don't know what to say."

A caller who identified himself as Kermit Blackwood, a 53-year-old Black Windham County resident, described the proceedings as "a little bit ridiculous."

"I think the name of the brook should be 'Empathy Brook' so everyone can think about what this means to them ... and not put white guilt onto people or get into this vindictive protectionism.

"Because this is about inclusiveness and bringing our community together," he continued, "not dragging the whole country's BS into our small, tightly knit community."

The hearing was stretching into its third hour.

"This is very disturbing to me all the way around," Post said. "I think we've bungled an opportunity to really have very in-depth discussions."

He said the renaming effort should start again, "but it should start again different."

"I hope we can put this rancor and discord behind us, because if we can't, there's no hope for racial justice," he said.

The library board voted by voice, united in opposition to the name change. "The petition is not accepted," Post said, bringing the meeting to an abrupt close.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.