- Courtesy of Cabot Creamery Co-operative

- Michael LaCroix of Barnard at Open Farm Sunday

“It’s not what you pictured, is it?” Robert Foster, the farm owner, asked me.

“No, I pictured something a little more like Little House on the Prairie,” I said with a laugh. I’d imagined farmhands milking cows one by one into a metal pail. But as I surveyed the barn, occupied by more than 400 cows, the idea seemed ridiculous. Laura Ingalls Wilder would have balked at what she'd see today: robots milking the cows, microchips monitoring every activity and machines mucking the stalls.

The Fosters are one of the farm families who own Cabot. The farmers who started Cabot in 1919 — a century ago — used the newest technology of the day to make their farms more efficient and sustainable. Today’s Cabot farmers still prize efficiency and sustainability, but the practice of farming has changed quite a bit over the past hundred years.

See for yourself how dairy farming has evolved on Cabot’s Open Farm Sunday on October 6. Foster Brothers Farm is one of 23 in the Northeast that will be open to the public for tours — yes, you, too, can go behind the scenes at the source of Cabot’s award-winning cheddar.

Here’s a sneak peek at what you’ll see on two of those Vermont farms.

Making the Cows Cozy

- Courtesy of Cabot Creamery Co-operative

- A cow lounging on her waterbed at Foster Brothers Farm in Middlebury

He explained this as we stood next to a large monitor that displayed detailed information about each of the 480 cows in the milking barn. He can keep track of how much milk each cow is producing and how often the cow moves. Sudden drops in either of those categories could indicate that a cow is sick.

- Courtesy of Cabot Creamery Co-operative

- Back scratchers in the barn keep cows comfortable.

“We used to handle them in groups,” he said. “Now we can handle them individually. They can sleep whenever they want, eat whenever they want and get milked whenever they want.”

Foster Brothers’ new dairy barn, finished in 2018, is home to eight milking robots — large stalls equipped with all sorts of tubes and machinery — that look like they’re straight out of science fiction. They don’t need to summon the cows for milking; the cows decide on their own when they’re ready and line up in front of the robots to await their turn.

The secret to the robots’ appeal? Food. Once a cow steps into the stall, the tubes contract as the robot attaches nozzles to the cow’s udder. The robot simultaneously dispenses grain into a bowl.

“Cows love consistency,” Foster added. He laughed as he recalled a time when a grain shipment came in late and the farmers didn’t realize they had to turn the refills on manually, so grain wasn’t dispensing. “I was dealing with some real angry cows,” he said with a chuckle.

I observed that, right then, the barn was nearly silent. Foster nodded. “Because they’re happy.”

On Open Farm Sunday, visitors to the farm will have the opportunity to taste the results for themselves. In addition to Cabot cheese samples, Foster Brothers Farm will provide Cabot Greek yogurt for smoothies. And visitors get to pitch in, too — they’ll make their own smoothies using a stationary bike that powers an attached blender.

Keeping It Sustainable

- Courtesy of Cabot Creamery Co-operative

- Robert Foster

The Foster Brothers Farm in Middlebury has long been a pioneer of sustainable agriculture. In the ’80s, Foster brought in the very first anaerobic digester, which generated electricity using methane gas released from cow manure. The digester was destroyed by a snowstorm in 2009, but since then, the farm has built a huge manure-based compost facility. Foster is trying to get other dairy farms on board. “I think compost is a good alternative to the digester,” he said.

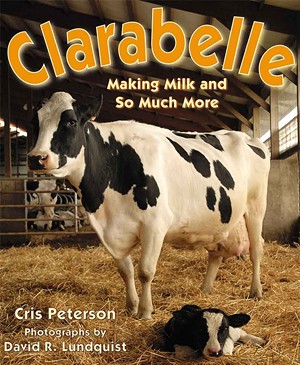

Foster started his career in farming when he was 10 years old. To inspire the next generation, the farm will offer a story walk on Open Farm Sunday. The children's book Clarabelle: Making Milk and So Much More, by Cris Peterson, will be printed and on display, so as young visitors tour the farm, they can read a book about dairy farming along the way.

The farm cares for 986 animals, including young calves, which visitors can also meet on the tour during Open Farm Sunday.

Teaching the Next Generation

- Courtesy of UVM CREAM

- Students from the UVM CREAM program

When I arrived at UVM CREAM in Burlington, the students I met with were running to hug one another, asking about each other’s summers and catching up. Mackenzie Fairchild, a junior in the animal science program, is starting her second semester working on the farm; Daisy Navin, a senior in the same program, worked on the farm over the summer.

Started in 1988, CREAM was the first program of its kind in the country. A group of students — 17 this year — manages the farm, which is part of UVM’s campus. The students milk and care for the cows, clean the stalls, and make all of the breeding and financial decisions.

The student farmers meet as a class to decide which bull will sire the next generation of calves based on features that will complement those of its mate. It’s a cow matchmaking service intended to produce the healthiest calves possible.

As Navin and Fairchild took me through the milking barn, the first thing I noticed was that it didn’t smell like manure. It smelled of fresh hay and grain.

Steve Wadsworth, the new program director at UVM CREAM, explained that it’s “because of the state-of-the-art ventilation system.” He added, “The tunnel ventilation is bathing the cows in constant clean air.” The milking barn was updated four years ago to include this, as well as a brand-new milking parlor that keeps track of how much each cow produces and the milk's weight.

Students hook up each of the cows to the milking equipment at UVM CREAM, getting to know the animals on an individual basis. As part of their regular tasks, the students keep up with the amount and quality of the milk the cows produce. Visitors will be able to taste samples of the different cheeses produced at Open Farm Sunday.

As we walked through the barn, Navin introduced me to a large cow lying on the floor of the pen: “This is Joy. We’re so proud of her.” Joy just won an award for producing milk with the highest fat content in the state.

“And this is one of my favorites, Gatsby,” she said. (Every cow, it seemed, is one of Navin's favorites.) Gatsby, she added, is “the bossiest lady; she’s in charge, and everyone knows it.”

The cows at UVM CREAM were very friendly and would approach the edges of the pen to greet us as we passed. Wadsworth noted that these cows are really loved. As he said this, Gatsby leaned over the pen and affectionately licked Navin's face.

Mothering the Calves

- Courtesy of UVM CREAM

- UVM junior Mackenzie Fairchild and Josie

When a calf is born, a group of one to three students is assigned to be its “mom.” The moms name the calf and take care of it, so that each calf gets really individual, attentive care.

We walked over to the adjacent barn to meet the teenage cows, and they all ran up to greet us. Navin introduced me to her “child,” Lollipop, making kissy noises at the teenage calf. She told me that the students often take their calves on walks around the barn. “They all have these goofy personalities,” she said with a laugh. “It really gets me.”

The students get four credits per semester for the program, but it’s love for the work itself that keeps them coming back, even waking up at 3:30 a.m. to do their barn chores. As we walked the farm, I was unable to tell the difference between the cows, but Navin and Fairchild knew the name and story of each one we passed.

“We’re sustaining Vermont agriculture by teaching the next generation,” said Wadsworth, “Wherever they go, they take this experience with them.”

The students at UVM CREAM are excited to share that experience on Open Farm Sunday, when visitors to CREAM can meet the students, tour all of the barns and meet the cows, too.

Navin worked a public event at another farm over the summer, and she recounted how much fun it was. “While everyone was there, we had a cow give birth!” she exclaimed. “The cows stop for nobody.” It truly gave visitors an experience of what everyday life was like on the farm.

Before my farm tours, the dairy world was a mystery to me. Now, when I pick up a block of Cabot Vermont Sharp Cheddar Cheese at the store, I’ll be picturing the friendly cows at UVM CREAM and high-tech milking robots at Foster Brothers Farm. I’m actually excited for my next trip to the grocery store — with my new perspective, the dairy aisle will never be the same.

Cabot Open Farm Sunday

Sunday, October 6, 11 a.m.-2 p.m.

There are 23 participating farms located across New York, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, and Rhode Island, including 4 in Vermont. Young visitors will get an activity booklet to guide them through the farms and send them on a farming scavenger hunt. They’ll also have the opportunity to earn an Open Farm Sunday patch.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.