- Tim Newcomb

A few weeks ago, as the surrounding forest turned golden, a man walked in the front door of the country inn Shari Brown has managed for decades. He was visiting from North Carolina and asked if she would rent him a room. He wasn't wearing a mask. "I'm like, 'No,'" Brown said, recalling her displeasure.

Brown has forgone some much-needed business in this way. Bookings at the Blueberry Hill Inn in Goshen are off by 80 percent since she reopened in June. But Vermont mandates that visitors from most places quarantine for 14 days before exploring the state, and Brown sees it as her civic duty to require compliance as best she can.

"We're the gatekeepers to Vermont," she said. "If I'm letting them come here, then I'm letting them go shopping, because nobody is checking when they go into the shop."

- Caleb Kenna

- Blueberry Hill Inn

Some would-be guests don't leave quietly. In July, a family on a road trip from Tennessee pulled up around dinnertime, asking to camp at one of the sites Brown set up this year for socially distant stays. The husband, who was unaware of Vermont's quarantine rules, became upset when Brown said no. Seeing two young children in the car, she reconsidered. But by that point her customer was in a huff. He called Brown "inhospitable" and drove off.

Around 9 p.m., Brown noticed headlights flashing through the inn's darkened windows. She went outside. The Tennessean had returned. It was late, and he and his children didn't have anywhere to pitch a tent. Could they camp, after all?

Over the last six months, Vermont has earned frequent praise from national press for being a bright spot in a country that has largely failed to control the coronavirus pandemic. Cases in the Green Mountain State remained very low through the summer, and no one has died from the disease since July.

- Caleb Kenna

- Shari Brown and Remy

Homegrown cases have swelled in recent weeks as the weather has gotten colder, pushing the state into a new, precarious period. Nevertheless, to a national audience, including the U.S. government's top infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the state offers a lesson in the power of careful leadership and a conscientious citizenry. Reopening has been slow and steady, nearly everyone wears masks, and residents keep their distance.

A key part of Vermont's strategy has been strict travel rules, for Vermonters as well as visitors. Any resident who leaves a specified 13-state area in the Northeast is told to quarantine for 14 days upon return. For Vermonters and out-of-state visitors, the requirement to quarantine when traveling to the Green Mountains from elsewhere in the Northeast is governed by a county-by-county map that changes weekly, according to case rates. Quarantine counties are depicted in red or yellow, non-quarantine counties in green.

These restrictions are the most stringent in the country — by a mile. Yet they still cracked open the door to tourists and the $2.8 billion they normally inject into the economy each year. Compliance depends almost entirely on the honor system.

This system of high expectations but no enforcement leaves Vermonters who serve tourists with a dilemma. They can shut out suspected scofflaws and lose even more money, or turn a blind eye to a rule that's supposed to keep their community safe.

A lean summer season led some in the hospitality industry to grumble that Vermont was losing tourists to other New England states. Then fall foliage hit, the state allowed lodging establishments to fill to capacity, and leaf peepers seemed to arrive in droves. For weeks, the state's tourist towns were lined with cars bearing faraway license plates. Few locals think those visitors bothered to quarantine first.

"I've not set foot in Woodstock," said Nicole Bartner, who runs the Hartland Diner, 12 miles away, "and everyone I know drives through basically with the windows up, as fast as they can."

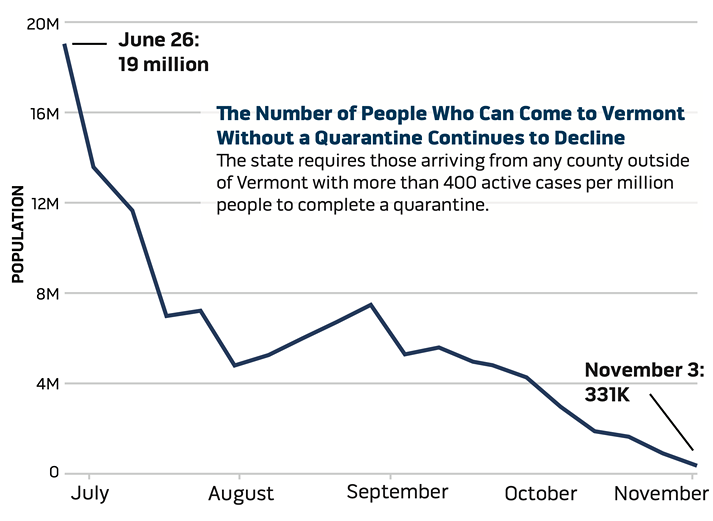

As cases surged nationwide in October, the map turned redder each week. As of November 3, just one in 1,000 Americans could visit Vermont without quarantining, the smallest number to date. The state currently restricts travel from all 10 counties that border Vermont.

So, as winter approaches, Vermont faces a double risk: Either visitors will obey the rules and stay away, whacking the state's economy, or they will come without quarantining — in a season that necessitates more time indoors, where the virus can spread more easily.

Lines of Defense

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Mike Pieciak

Of all of Gov. Phil Scott's restriction-loosening turns of the proverbial spigot, deciding how to resume travel was among the most consequential. By May, Vermont had suppressed the virus and was reporting just a couple of new positive cases each day, far fewer than in neighboring states. Scott charged the Vermont Department of Financial Regulation with devising a way to reopen the state's borders without importing the disease.

The department's commissioner, Mike Pieciak, oversees regulation of banks and insurance companies; his team, while not composed of public health experts, is versed in assessing and managing risk. Pieciak also turned to infectious disease experts and a private consultant to help apply those risk management principles to viral spread.

State officials wanted to take a conservative approach to reopening tourism, but they also saw an opportunity. Infection rates varied within states such as New York, where cities were initially the hardest hit. By measuring the virus at the county level, state officials decided they could open up regional travel sooner.

Pieciak introduced the travel map in early June, making Vermont the sole state to impose restrictions at the county level.

That wasn't the only novel aspect of the approach. Most states have gauged hot spots by looking at rates of recently detected coronavirus. Vermont sought a more precise way to measure the relative number of infectious persons in each county. Pieciak's office created an equation that weighted cases based on a rough estimate of where people were in their infection cycle. The older the case, the less weight it receives.

Using this algorithm, state officials set the travel threshold at 400 active cases per million residents. Visits between Vermont and any county above that rate require a period of self-quarantine. County colors are reassessed every week.

The threshold has no tested scientific basis, and there are no state- or county-level travel recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with which to compare the method. It's simply an estimate of risk.

"We landed at 400 as a ceiling that looked similar to Vermont, in terms of disease prevalence, with a little more of a buffer," Pieciak said. Vermont's threshold is nearly twice as strict as those used in some other states in the Northeast, he acknowledged.

The implications are dramatic. Massachusetts' travel restrictions kick in for states with an average of 10 or more daily cases per 100,000 residents. As of November 3, more than 72 million Americans could freely travel to Vermont's southern neighbor; only 331,000 from six rural counties could travel to Vermont.

- Andrea Suozzo ©️ Seven Days

- Source: Vermont Department Of Financial Regulation

Another notable difference: enforcement. While Massachusetts and some other nearby states threaten to fine travelers and residents who ignore their rules, Scott's administration has left compliance to an honor system.

Though data are spotty, Vermont's method may have worked to reduce travel. During the summer season, visits to Vermont lodging establishments from residents of green counties were down by half compared to 2019 but down by 76 percent from counties that would have required quarantine, according to cellphone mobility data analyzed by Pieciak's office. The analysis is not precise, and it did not include travel from many counties whose status changed during July and August.

Flight ridership at Burlington International Airport is severely depressed, as are visits to highway welcome centers. Road traffic was down in August at nearly every site monitored by the Vermont Agency of Transportation.

The best evidence that the system is working is that the rate of coronavirus infections in Vermont remains lower than surrounding states. Nonresident tourism has not been identified as the source of large outbreaks.

"[The travel map] is hard to defend in terms of where it came from," Health Commissioner Mark Levine said in a recent interview, acknowledging that the state's algorithm isn't supported by any evidence-based study, "except for the fact that it has served us extremely well, and that should be enough."

Who's on Watch?

- Tom Mcneill

- Tourists outside the Woodstock Inn & Resort

The fall foliage around Woodstock was well past peak on a recent gray Saturday, but the village was still packed. A steady stream of visitors posed by pumpkin arrangements, briefly removing their masks for the perfect #fallvibes photo. A dozen groups lined one sidewalk, waiting their turn to shop at Vermont Flannel, which was enforcing a 50 percent capacity limit.

The wait was relatively short, according to PJ Eames, who owns Clover Gift Shop across the street. She's seen the queue stretch for blocks in recent weeks. A line had also formed outside her narrow storefront, where a greeter used a thick black rope to control flow through the entryway.

"We are thankful that we have business," Eames said. "But it comes with mixed emotions, because we still want our state to be safe."

Last month, a customer volunteered to Eames that she'd traveled to Woodstock from New York City. "I'm so glad we can come here now without quarantining," the woman said. Eames politely told her customer that she was mistaken. But the woman insisted the shopkeeper was misinformed.

That evening, Eames posted the state's travel map to her shop's Facebook page. "Please abide by these rules," she wrote. "Vermonters have been diligent, and as a result our cases have remained low."

But Eames doesn't question customers about their travel. It would be bad for business and hard on her employees, who she said already have their hands full trying to enforce a statewide mask mandate, social distancing and hand-sanitizing policies. "I assume that they have taken up that issue with whatever lodging they're staying in. I hope," Eames said. "We kind of just have to trust people will be good-natured."

The Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development does not ask retailers to post or enforce the ever-shifting travel restrictions. Instead, the onus is on lodging establishments — sort of.

To stay overnight in Vermont, guests must sign a "certificate of compliance" attesting that they've reviewed the online travel map and are fulfilling their obligations. Unless their county of origin is green, they need to quarantine at home or in Vermont for 14 days; they can cut that period short by a week if a laboratory COVID-19 test shows they're not sick with the virus. The state accepts pre-arrival quarantine only if the visitor travels directly to Vermont by car.

- Tom Mcneill

- Clover Gift Shop

Lodging establishments are not supposed to allow anyone with COVID-19 symptoms to check in, but they need not ask questions that might, for instance, reveal whether a guest has actually reviewed the map. For visitors who make reservations online, completing the certificate can be as simple as checking a box. Inns and hotels must keep the forms for 30 days, but the state hasn't been collecting them.

Each business then decides whether to have the quarantine talk. Patrick Fultz, co-owner of the Sleep Woodstock motel, calls guests who make reservations online to ask questions about their travel plans "to make sure that you meet Vermont compliance," he tells them. So many guests have canceled after the talk, or because their county flips to red before they arrive, that Fultz has stopped pre-charging credit cards — the fees were adding up. Meantime, his business is down by half.

Some customers take offense at any whiff of interrogation, innkeepers say. Others will shop around for a place that won't ask. Still more approach the transaction as a negotiation.

"The other day we received a call that verbatim asked, 'How seriously are you taking this?" said Brian Maggiotto, general manager of the Inn at Manchester, an upscale hotel that draws visitors from New York's Capital Region and the Berkshires in Massachusetts.

Twice his staff has turned away customers after they arrived and admitted to not following the rules. "They begrudgingly understood," he said, and planned to drive to New York instead.

Maggiotto's staff keeps the latest travel map handy for those conversations, which he worries can give some visitors the impression that Vermont doesn't want them here. It can puncture their fantasy of a cozy, flannel-clad getaway.

"We are the front line of how people feel when they think about Vermont," he said. "The messaging from Vermont has made this harder for us."

Inns that try to more actively enforce the travel restrictions may succeed only in pushing guests to services such as Airbnb or to lodges just across the border, contends Tim Piper, president of the Vermont Inn and Bed & Breakfast Association.

Piper argues that inns are "taking an arrow" for the state by administering the compliance certificates. But there's also broad belief that plenty of establishments treat the paperwork like any fine print.

"The current system is putting front desk clerks in the position of being gatekeepers for Vermont — with the conflict of having rooms to sell," one front desk clerk at a major corporate hotel told Seven Days.

- Tom Mcneill

- Patrick Fultz

The clerk, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation by her employer, said management has directed her not to ask guests about their county's color on the travel map. They've also told her to sell a room even when she believes the guest isn't being truthful on the compliance certificate.

It's left her torn between keeping her job and knowingly leaving housekeepers, other service workers and her community at a higher risk.

"The fact that there is no penalty for the guest or lodging establishment to ignore the rules when a guest checks in is a huge hole that must be closed if we are to protect Vermont," she said.

Scott doesn't seem to have an appetite for such penalties, though he said at an October 27 press conference that the state may canvass hotels to see whether they're collecting the certificates as required. Pieciak added that the online travel map is being widely viewed, an average of 43,000 times per day — a sign that the requirements are well known.

Still, Vermonters have filed nearly 180 complaints against lodging properties through a Vermont Department of Public Safety tip line since the travel map was introduced. Just 30 have been flagged for "educational" follow-up with a business, Public Safety Commissioner Michael Schirling said.

"Most of what we've run into," he said, "have been perceptions of noncompliance."

Brown, of the Blueberry Hill Inn, has been frustrated by a feeling that other innkeepers aren't as diligent as she tries to be. She thinks the industry would more actively screen guests if it weren't under such financial duress.

Even to her, the effort sometimes seems futile. When the man from Tennessee returned to her inn that July night, headlights flashing, she let his family make camp. "He's already here," she reasoned. "What was I to do?"

Locals Only

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Janet Martinez

Janet Martinez has been hearing a lot of war stories. Unlike many businesses in Stowe, her bar, Burt's Irish Pub, caters to locals. Lately, those who come by want to blow off steam about an unsettling tourism season.

"The level of frustration is crazy," she said.

Martinez has owned the business for 17 years. Aside from a conspicuous lack of tour buses, which are not running this year, the crush of visitors to the area felt the same. The spigot seemed wide open.

Her assessment: "They're all coming from places that are red zones, and they're not telling the truth."

She relayed one story of a group that was seated to eat after providing a Burlington phone number for mandatory diner logs kept in case of contact tracing. As they opened their menus, a server overheard a comment that indicated one of them was from a red county. The server later discovered that the local phone number was actually a hotel line.

Martinez has settled on a solution: She'll stop serving customers who can't show a Vermont driver's license, at least for the winter. State and federal public accommodations laws don't bar discrimination based on state of residence, and she expects that making the bar a locals-only space will put her service-industry clientele at ease.

At least one other business has vowed to follow suit. Thomas Moog, who owns Moog's Place in Morrisville and Moog's Joint in Johnson, announced on Facebook last month that only Vermont residents would be allowed into the restaurants.

Online, Vermonters have served a function somewhere between volunteer health officers and neighborhood watch members. A few weeks ago, a New York State resident asked a Burlington Facebook group for breakfast spot recommendations along her drive from Albany to the Queen City, where she was finally taking a long-planned weekend trip. Within minutes, one local looked up the poster's county and said "unless you are currently quarantined, your weekend will be off."

The pile-on was on. "The problem is we are trying to keep our cases low and are doing it," someone wrote, "but when people come from so-called hot spots for no reason other than they want to just hang out in VT, it puts all of us at a greater risk." He suggested she travel to Plattsburgh instead. The woman deleted the post. She did not respond to an interview request.

The biggest stir, though, came when a photo of a wedding at the iconic Woodstock Inn & Resort began circulating online. Bartner, the Hartland diner operator, helped it go viral. The photo showed rows of wedding guests watching an outdoor ceremony without masks.

"I am certain these people are not locals," Bartner wrote at the top of a lengthy post. "I am also certain they did not quarantine the required two weeks upon entering Vermont."

Her post contrasted in detail what she saw as a reckless money grab by the resort with her own extra efforts to keep her diner in business during the pandemic, down to the four gallons of gravy and five gallons of corn chowder she personally makes each day. The photo wasn't just an indictment of the revelers' "self-centered ignorance" and "entitlement." It was a symbol of a system that is "rigged" for the elite, the viral droplets a visceral extension of the pernicious relationship between the wealthy and the working class.

"It's galling when they're endangering the entire community," Bartner told Seven Days.

Her post, shared 1,900 times, urged friends to boycott the resort. A subsequent GoFundMe for her diner raised $2,450.

As the image spread, state officials and local village trustees got involved. A state spokesperson told the Valley News that the wedding was "largely in compliance." The resort issued a statement saying the photo had been an "unfortunate misrepresentation."

"Guests arrived wearing masks, then removed them to consume a beverage during the ceremony, which is within existing state and local protocols," the resort claimed.

A Place Divided

Hanover, N.H., Town Manager Julia Griffin has been outspoken in urging residents to help slow the spread. Over the summer, she wrote an op-ed for the Dartmouth student newspaper exhorting the Ivy Leaguers to be less "selfish" and to "smarten up" by obeying health directives.

A couple of weeks ago, as she was standing in line for vegetables at the Norwich Farmers Market, she wondered: Had she become a scofflaw, too?

The market is a stone's throw from Hanover, but it's separated by the state line. Days earlier, Grafton County, where Hanover is located, flipped to yellow on Vermont's travel map. Technically, all nonessential travel now required a lengthy quarantine. Crossing the Connecticut River bridge for locally grown produce seemed like a gray area. "It is nice but not essential. Should I have been there?" she asked herself.

Griffin was facing perhaps the most Vermonty dilemma of the pandemic. New Hampshire's state government still classified community transmission in Grafton County as "minimal," even as Vermont had deemed it an elevated travel risk. What's more, when Grafton County flipped to yellow on October 13, Windsor County, home to the Norwich Farmers Market, had a slightly higher rate of active COVID-19 cases.

Upper Valley residents hardly notice when they cross between jurisdictions. "There's not really a line between our communities, even though they're in different states," said Dan Fraser, who co-owns Dan & Whit's general store in Norwich.

Vermont's algorithm is drawing a line, for now.

The change, with its significant implications, struck some in the area as absurd. Local lawmakers complained that it would disrupt cross-border youth sports and skiing programs, the Valley News reported, even though many of the kids go to the same interstate school district. Court Vreeland, a chiropractor and co-owner of the Vreeland Clinic holistic health practice in White River Junction, said the state's threshold seemed arbitrary, given what he saw as a negligible difference in infection rates between the intertwined communities.

"In the spirit of letting people get back to their lives, I think this needs an exception around here," he said.

His family has changed some plans anyway. He and his wife intended to celebrate their wedding anniversary with a night out, but their babysitter lives in Lebanon, N.H., and their restaurant reservation was there, too. Vreeland worried about how patients might perceive his business if someone saw him dining in violation of the state public health order. They got takeout from a Vermont restaurant instead.

Vermonters in the Upper Valley confused by the recent restrictions are touching on a complaint that lodging establishments have been making for months. The state has been quick to shut down travel beyond its borders, even though 11 of Vermont's 14 counties as of November 3 weren't low-risk by the same measure.

"A lot of us struggle with the hypocrisy of it," said Maggiotto, the Inn at Manchester manager.

His business was one of the first to join what is now the Vermont Lodging Coalition, a unified lodging trade group formed in the pandemic's wake. One of the coalition's key requests is to loosen the travel restrictions, including a call for reciprocal travel guidelines among Northeast states. The group argues that hotel stays are just as COVID-19-safe as grocery store visits and golf courses.

State officials defend the Vermont county exemption on the grounds that the Vermont Department of Health has a well-resourced contact-tracing program with deep knowledge of every case within Vermont's borders, and thus more control over community risk. That information isn't available from other states.

Last Friday, though, Gov. Scott said he was mulling a narrow exception to the cross-state restrictions for certain activities in the Upper Valley.

The current surge in cases around the Northeast doesn't bode well for the push to open Vermont's borders. Though some in the lodging industry sounded optimistic that the governor might consider an adjustment before ski season, Levine was quick to snuff out that hope.

"Nobody, seemingly across state government, is interested in liberalizing it further," he said in an interview, "especially when we keep seeing red and yellow zones encroaching more and more on the state."

Alternatives to Vermont's onerous quarantine approach do exist. Alaska and Hawaii both welcome travelers who take a COVID-19 test before arriving and submit proof to the state. But point-in-time tests aren't as reliable prevention measures as quarantining. Those states also have the advantage of isolated borders.

"It is challenging to be an island in northern New England," Levine said. "You can't really be that."

Long Winter Ahead

If the ski season started today, nearly 80 percent of Vermont resorts' typical customers would be barred from coming to the slopes for an impromptu weekend. That would deliver a severe blow to the state's economic recovery.

Many resorts may be able to limp along by relying on higher resident demand and by encouraging regional visitors to plan their trips around a quarantine period rather than snowfall. Other businesses linked to skiing may not be able to stay open.

Such widespread travel restrictions "would be a catastrophe," said Margaret Cating, owner of the Lodge at Bromley, a family-oriented hotel at the base of Bromley Mountain. "My hotel [would] have to shut down" for the season, she added.

No matter the restrictions, compliance will remain a challenge. The Vermont Department of Tourism and Marketing is planning a campaign to increase awareness of the rules, but resorts aren't planning to probe their guests' travel history beyond asking them to sign a state-mandated compliance form.

"Given the nature of the requirements, we are unable to verify if visitors to the resort meet the requirements, but we urge you to do the right thing," Killington Resort's website reads.

Cating and others are counting on the region's residents to adjust to indoor safety routines so the latest surge doesn't linger for months.

"In the Northeast, people are pretty smart," she said. "They just have to reset their habits for wintertime. I feel pretty confident that they'll start heading towards the green."

This wave already has one novel feature: Vermont isn't immune. Daily cases and hospitalizations have hit levels not seen since April, and multiple outbreaks are unfolding concurrently.

The health department has traced four recent COVID-19 outbreaks to an earlier one at a Montpelier ice rink. Those initial cases involved locals who ignored the cross-state travel guidance, Scott said at a recent press conference.

"This is travel by Vermonters, not out-of-state visitors," he emphasized.

Subsequent outbreaks have occurred at two workplaces, a K-12 school and Saint Michael's College, which canceled in-person classes to suppress further cases. At least 112 people have been infected, and at least 19 workplaces and schools have been exposed.

Levine deemed the situation a "wake-up call" about the large risks of small gatherings, especially when guests are traveling. He also warned that anyone whose Thanksgiving plans involve travel, including college students returning to Vermont, should begin planning their quarantine period.

In the long winter ahead, Vermont will continue to lean on its travel rules to guard the state from too many reckless tourists. But the rules will also need to protect Vermonters from themselves.

That's been true all along. For months, Outdoor Gear Exchange, a sporting goods store on Burlington's Church Street Marketplace, has been one of very few businesses to force customers to answer questions about their travel before they can shop for new gear. Some days, employee greeters have turned away 50 or more customers who didn't pass the test, executive director of retail and service Brian Wade said.

On September 13, one of the employees told a pair of men, one from Burlington and one from Colorado, that they couldn't come in. The Colorado visitor became frustrated, believing his county was "green," even though Vermont deems every county more than a day's car drive away to be red.

His Burlington friend, according to Wade, wouldn't answer questions about his own recent travel, then tried to walk inside to find his wife. The greeter stepped in front of the door, and then ended up on the ground, the victim of an alleged assault. The shopper, Bill Atkinson, is due to be arraigned in court next month. Atkinson declined to comment for this story, but he previously told the Burlington Free Press he was embarrassed by the incident.

"That's not who I am. That's not how I conduct myself," Atkinson told the paper.

The store has since replaced its greeters with private security guards.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.