- Caleb Kenna

- Stephanie Carvey working with kids at Rekaroo's Childcare in Rutland, Vt.

Host Jane Lindholm moderated a 36-minute conversation between a panel of experts and a series of callers, many of whom shared horror stories about seeking care that’s increasingly difficult to find.

One exchange stood out from the rest, at least to many parents listening to the program. It was a call from “Charles from West Rutland,” which aired at the 28:20 mark.

“I’m coming at this from a different angle,” he said. “I just don’t understand this appetite for this ‘womb to tomb’ coverage that we seem to have in Vermont … I’m not interested in publicly funded child care. You should wait until you can afford to have children like my wife and I did … This is not sustainable.”

What can you do to help solve Vermont’s child care crisis?

- Attend the Statehouse Rally on Wednesday, March 13.

- Call or write your legislators.

- Share your story with Let’s Grow Kids.

- Join an Action Team of supporters in your community.

Do it all at letsgrowkids.org.

Janet McLaughlin, interim CEO of nonprofit Let’s Grow Kids, responded, pointing out that “when you actually look at the cost of housing, the cost of education in Vermont now, it is different than when you and your wife were starting your family.”

In the last 30 years, housing costs have risen 200 percent, and higher education costs are up 300 percent. Wages have not risen at the same rate. For many Vermont parents, a month of child care costs as much as — or more than — rent or a mortgage payment. And that’s just for one child.

But, said McLaughlin, “I think the key thing to remember is that we need taxpayers in Vermont. And we will not have taxpayers if young families can’t live here, can’t work here and can’t have more children who are then going to live in Vermont.”

Child care advocates aren’t the only ones making this argument. Elected officials across the political spectrum now embrace it. They’re confronting some alarming facts: Vermont’s population is the second oldest in the country, and the state is facing a massive number of retirements on the horizon. It needs all the workers and taxpayers it can get. In fact, last year Vermont made headlines around the country when it announced a plan to pay telecommuters up to $10,000 to move here.

In order for young parents to work outside the home, they need access to child care, and they’re having trouble finding it.

- Caleb Kenna

- Rekaroo's Childcare in Rutland, Vt.

Right now, some young parents who want to work are dropping out of the workforce because they can’t find care for their kids. Vermont can’t afford to lose them.

Let’s Grow Kids’ mission is to ensure that every Vermont family has affordable access to high-quality child care by 2025. It’s tackling the problem by urging its 30,000-strong network of supporters to help pass legislation that will make major new investments in high-quality, affordable child care — and incentivize employers to help, too.

“We’re working across the aisle on this,” said Rep. Theresa Wood (D-Waterbury), lead sponsor of a comprehensive bill introduced last month with 70 cosponsors. “This is an economic issue for the entire state as much as it is for individual families.”

To understand the complexities of the problem, consider another voice from the Rutland area: that of Stephanie Carvey.

A southern Vermont native, she’s experienced the system from both sides, as a parent and a child care provider. The 32-year-old mom of two is the director of Rekaroo’s Child Care in Rutland. She has eight years’ experience in the child care field and a bachelor’s degree in elementary education from Castleton University.

Carvey continues to seek additional certifications and hopes to earn a master’s degree someday. “I’m a glutton for punishment,” she joked.

Seriously, though: “I like school,” Carvey said. “I like to be an example.”

Whether she wants to be or not, Carvey is a great example of what’s right — and wrong — with Vermont’s child care system.

A Big Responsibility

- Caleb Kenna

- Director and lead teacher Stephanie Carvey with Floor Manager Amber Foehl at Rekaroo's Childcare in Rutland, Vt.

Carvey manages a staff of 25 teachers and assistants at a center that cares for 70 kids. Like many child care centers, Rekaroo’s has a lengthy waiting list, including several expecting parents who will need care when their child is born.

Carvey is responsible for much of the accounting, doing payroll and making sure the center is complying with state rules and regulations. She conducts ongoing staff trainings and seeks out professional development opportunities for Rekaroo’s employees. She attends outside meetings for groups including the Rutland Directors Starting Points Network, an organization of local child care center directors.

Ideally, as director, Carvey would provide direct professional support by evaluating and coaching staff on their teaching, and focusing on providing high-quality care.

Instead, for the past few months, Carvey has been doing double duty as the director and as a lead teacher in the preschool classroom. She’s been in that role since the last lead teacher — who also had a bachelor’s degree in early education — left to take a job in the local public school system.

Carvey now spends her weekdays teaching 3- and 4-year-olds, finishing her administrative work after her own kids, ages 9 and 4, go to bed. Her kids often accompany her to the center on the weekends so she can finish up her work.

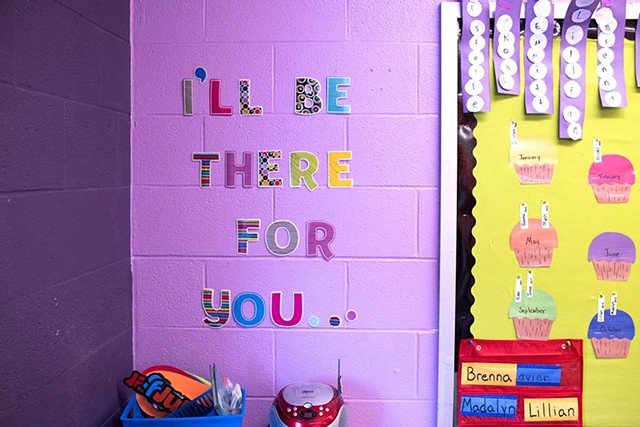

Carvey’s classroom isn’t an afterthought, though. Engaging educational displays and art projects cover its lavender cinder-block walls.

During a tour of the center one day in February, Carvey pointed to a row of art projects on the wall in her classroom. The children made snowpeople using cutouts of circles and squares, and a red ribbon. This wasn’t just a random craft project, Carvey explained; the kids were demonstrating their ability to distinguish shapes and put them together appropriately to make a snowperson.

Once the shapes were arranged, the kids had to glue them in place. They used glue from bottles and had to squeeze out the right amount, demonstrating fine motor skills.

Both of those abilities are considered developmental milestones for preschoolers, Carvey noted. To underscore that with parents and the center staff, she posted pictures of the kids’ work on the Rekaroo's Facebook page using the hashtag #meetingmilestones. It’s a practice that other area centers use, and this kind of communication to parents is a marker of quality.

Though two other adults were in the room during the tour, Carvey occasionally interrupted her narration to address the kids. “Bless you. Cover [your mouth]!” she reminded a child who sneezed. “What’s up, bud?” she gently asked a boy who was leaning against a wall, crying.

Then another preschooler had an accident. “I pooped,” he told one of the aides. When she took him to the bathroom to change his clothes, Carvey paused the tour to take over the class. With preschoolers, there’s constant tension between managing the unexpected and supporting early education that leads to healthy development.

This safe, nurturing care and early education is vital: Studies have shown that 90 percent of brain development occurs between birth and age 5.

In an interview after her VPR appearance, Janet McLaughlin of Let’s Grow Kids noted that the care and learning children experience between birth and age 5 “puts them on the trajectory for the rest of their lives.” If young children don’t receive quality care during these formative years, she said, “the research shows there’s a good chance we’ll be paying more down the line.”

Compensation Crisis for Early Educators

- Caleb Kenna

- Stephanie Carvey telling a story to kids at Rekaroo's Childcare in Rutland, Vt.

In 2017, the median income for full-time workers in Vermont was $45,058, or roughly $21 an hour, according to the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey.

Most child care or preschool program directors or administrators in Vermont earn a little more than that — their median hourly wage is $22.14, with a median annual salary of $46,050, according to the Vermont Department of Labor.

But Carvey said the average pay for a child care center director in her area is between $14 to $18 an hour. Her position does provide her what she calls “meaningful compensation at a livable wage,” but she still makes less than $40,000 a year. Until recently, Carvey was working a second job as a shift supervisor at a local restaurant to supplement her income.

Forty thousand dollars also happens to be the amount of her student loans, which she doubts she will ever be able to pay off. “I haven’t even started,” Carvey confessed.

She and her husband and kids live in an apartment in Rutland; they can’t afford to buy a house.

Because Rekaroo’s is a relatively new center, it’s not able to offer many benefits yet — no health insurance, no dental insurance, no 401(k) or retirement plan. Carvey couldn’t say whether that’s true of most early educators working in child care programs, but she’s never worked for one that offered any of those.

In fact, Carvey is currently without health insurance. Her job doesn’t offer it, and neither does her husband’s. They can’t afford a Vermont Health Connect plan. Fortunately, the kids are covered through Dr. Dynasaur, a state program that offers free or reduced cost health insurance for children.

Despite all of this, Carvey loves her job and feels appreciated — by the center’s owner, by the teachers, by the parents. “That’s what keeps me going,” she said.

Carvey’s financial situation is difficult living on a director’s salary, and the situation is more dire for other child care workers. According to the Department of Labor, preschool teachers earn a median hourly wage of $14.57 and a median annual salary of $30,310 — not much for someone with a bachelor’s or associate’s degree in early childhood education. Early learning professionals are actually the lowest-paid college graduates of any degree program.

Because of this pay scale, Rekaroo’s has lost multiple qualified teachers to jobs in the school system, such as the one Carvey was forced to cover for in the fall. According to Let’s Grow Kids, kindergarten teachers with similar qualifications to pre-K teachers make, on average, $24,000 more. And they get benefits.

Child care assistants and infant and toddler teachers are paid even less than preschool teachers, making those positions even more difficult to fill. According to the Vermont Department of Labor, they earn a median hourly wage of $12.71 and a median annual salary of $26,440.

“People get paid more to clean houses than they do in child cares,” said Carvey. “There’s not much to keep them from saying, 'Forget this, Five Guys opened across the street.'”

Said McLaughlin of that pay scale: “It is not a livable wage. Essentially right now what we’re doing is balancing this system on the backs of early childhood educators.”

Parents Can’t Pay More

Why not solve this compensation problem by raising the cost of care?Rekaroo’s owner Tereka Hand doesn’t think her clients can afford much more. Infant care, the most expensive kind, costs $230 a week at Rekaroo’s. “It’s hard to say that out loud to someone,” said Hand. When she meets with new parents touring the center, she said, “They’re like, ‘Is that a week? Or a month?’ It hurts your stomach.”

That’s compounded for parents with multiple kids needing care. Said Carvey: “Once you have two kids, it’s just scary. I waited until my first child was in kindergarten before I had another one.”

Carvey and Hand say that paying staffers more could mean taking away from other aspects of quality, and that’s not something they’re willing to do. They’ve worked hard to meet the requirements of the state’s voluntary Step Ahead Recognition System (STARS) for child care programs, earning three stars out of a possible five. They intend to push that higher.

Parents like Jennifer Burrier agree that Rekaroo’s is worth the expense. Her son is “so happy there,” she said. A single mom who lives nearby, Burrier has three kids, ages 16, 11 and 4. She works as a pharmacist in the intensive-care unit at Rutland Regional Medical Center. Burrier pays roughly $200 a week to send her 4-year-old to Rekaroo’s. “That’s as much as my mortgage,” she said.

This is what’s driving Vermont’s child care shortage, said McLaughlin: “Parents can’t afford to pay more. Providers can’t afford to work for less. That’s why supply isn’t growing with demand.”

A Workforce Challenge for Vermont

- Caleb Kenna

- Jennifer and William Burrier

Sometimes Burrier has to respond to medical emergencies in the ICU. When that happens, she worries about being late for pickup.

“If something happens and I get slammed at work, I can’t just walk out,” she said. “More often than I would like to, I end up calling and saying, ‘I’m going to be 15 minutes late, but I’ll be there, I promise!’” she said.

And Burrier worries about how to fill the gaps in her son’s care. When her older boys are home, they can watch him. Sometimes her father and stepmother can take him, but they work, too, and are not always available. And Burrier can’t just bring him to the hospital with her.

So when Rekaroo’s calls a snow day or closes early for in-service training, or when her son is sick, Burrier often has to take off work to care for him.

All Vermonters rely on health care workers in emergency situations to be reliably at work and focused on their jobs. But Burrier’s situation illustrates the ripple effects a lack of access to child care can have — in her case, on the quality and reliability of health care.

Burrier’s experience is consistent with that of other local parents of young children who work outside the home, according to Shelley Sayward, vice president and assistant general counsel of Casella Waste Systems. The company employs 2,200 workers across six states, including 650 in Vermont.

Casella’s entire administrative staff — those in finance, accounts payable and the call center — work out of the company’s Rutland headquarters. Two years ago, Sayward says, Casella surveyed these employees to find out how they were affected by child care issues.

“What we found was clearly a severe lack of infant care,” she said. That has hurt the company’s ability to retain employees who are new parents.

The survey also found that when employees miss work, it’s often because of a child care issue. And, Sayward added, “some employees said, ‘I can be really distracted during my workday if I’m worried about when I need to pick up my kids.’” Not a comforting thought for employers — or customers.

As a result, Casella worked with Let’s Grow Kids to experiment with ways to help. The company approved greater flexibility for parents around scheduling, allowing employees to arrive a little later or leave a little earlier, as needed.

Casella also instituted an employee scholarship program, aided by a match scholarship from Let’s Grow Kids. The company now gives $200 to $270 a month to employees to spend on child care expenses. Employees who enroll their kids in high-quality child care programs are eligible. They can even set up a dependent care account to get the money tax-free.

The employee feedback has been very positive, said Sayward. Managers have reported that “it definitely makes a difference in level of commitment, enhanced concentration and cutting back on absences,” she added.

Casella plans to make this program an official part of its benefits package, but Sayward wants to see the state offer an incentive to act. Her message to Vermont lawmakers: “Give us a hand!”

A Three-Sided Solution

- Caleb Kenna

- Rekaroo's Childcare in Rutland, Vt.

First, it would expand the financial assistance program so that it makes a real dent in the cost of care. Injecting more money into the program will help offset costs for parents and could help raise wages for early educators. Right now, middle-income families are spending up to 40 percent of their income on child care, even with financial assistance.

This financial assistance could be described as an investment in the state’s future workforce. Jennifer Burrier, the pharmacist whose son attends Rekaroo’s, doesn’t qualify for financial assistance now, but she did when she was a full-time pharmacy student at the Albany College of Pharmacology’s campus in Colchester. She called it “a lifesaver.”

“I wouldn’t have made it through pharmacy school without it,” Burrier said.

Second, the legislation would offer scholarships to early educators who seek additional certification, as well as create a student loan repayment program for early educators who received a degree in the past five years. This would help providers improve the quality of care they’re giving, and would encourage students to pursue a career in the field.

Stephanie Carvey strongly supports the bill and approves of these incentives for child care workers to enter the field. She noted, though, that while the bill under consideration offers scholarships for providers who don’t yet have their degrees, it doesn’t include anything about loan repayment for veteran early educators who have had their degrees for more than five years.

“Can’t hate on it, though,” Carvey said of the bill. “Even if it’s not perfect, it’s something!”

Lastly, the legislation would give a tax credit to businesses like Casella that invest in helping their employees pay for child care. Sayward is all for it. She calls the bill “a great step.”

At the very least, said McLaughlin of Let’s Grow Kids, “it encourages a lot more employers to examine what they’re doing.”

Time to Put on the Pressure

- Caleb Kenna

- Rekaroo's Childcare in Rutland, Vt.

Rep. Wood appreciates that he’s listening and pledges to work collaboratively with him, but, she said, that amount is “not enough.”

“We have to be serious about our investment,” Wood insisted. “There are no party lines on this. We have to tackle this issue.”

Let’s Grow Kids is ready to mobilize the troops. The organization has already assembled a diverse coalition of stakeholders and more than 30,000 Vermonters who support its mission. On March 13, Let’s Grow Kids will hold a Rally for Kids at the Statehouse to bring its message to Montpelier.

For those who can’t attend the rally, there are other ways to help. Let’s Grow Kids is encouraging parents and child care providers to share their stories and to contact their senators and representatives.

“We want people to reach out to their legislators directly,” said McLaughlin.

The group is also keeping a close watch on the legislative process in the Statehouse, to stay on top of the debate and any new developments. The organization will continue informing supporters via social media, email and in-person meetings around the state.

“If we all work on this together, we can actually solve this problem,” said McLaughlin. “But we need to act now to pass legislation that makes a core commitment to Vermont’s children that we can build on in the future.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.