- Diana Bolton

Selectboard chair Catherine McMains, who has lived there for 31 years, describes her neighbors as artists, retirees and liberals — not "wealthy folks," like those who live in Charlotte, the richest town in Chittenden County.

"We don't see ourselves that way," she said.

But today, few Vermonters could afford to move to Jericho's verdant foothills, where homes sold at a median price of $430,000 last year.

The high cost of housing in Jericho did not come about overnight.

About this Series

Seven Days is examining Vermont's housing crisis — and what can be done about it — in our Locked Out series this year. Send tips to

[email protected].

These stories are supported by a grant from the nonprofit Journalism Funding Partners, which leverages philanthropy and fundraising to boost local reporting. For more information, visit jfp-local.org.

Chuck Lacy, a curmudgeonly former farmer and president of Ben & Jerry's who runs a small venture capital fund, has lived in an older home in Jericho Center since 1988. A few years ago, he wanted to add another apartment to his duplex for his mother. Zoning restrictions on triplexes at the time forced Lacy, 66, to instead build a separate detached house — and to follow his curiosity to learn how his town controls land use.

Lacy started reading old documents: town plans, defunct zoning bylaws, meeting minutes and newspaper clippings. The faded files helped illuminate Jericho's decades-long evolution from a farm town to an upscale bedroom community. As white professionals moved in during the 1960s, residents erected an invisible firewall against perceived threats to their rural oasis. They drafted and adopted local zoning rules that outlawed mobile home communities and mandated large lot sizes that curtailed starter homes. Fewer, and bigger, homes were built, commercial development was strictly controlled, property values rose, and resident incomes skewed higher.

"It was just so clear," Lacy said, "how intentional reserving most of Jericho for people with money has been."

Vermonters pride themselves on the idea that the Green Mountain State is a welcoming place for people of all lifestyles. Yet Vermont's chronic shortage of housing is transforming swaths of its cities and towns into havens for wealthy, aging white people. The latest, pandemic-fueled price surge has disrupted the economy and affected middle-class families. Housing's cost has become impossible to ignore.

In this "Locked Out" series of stories throughout 2022, Seven Days has traced the contours of the housing crisis. Young families have been locked out of homeownership or pushed to locations far from where they work. Costs have soared for hard-to-find rentals, displacing residents. Public schools can't hire teachers because there's nowhere for them to live. More companies have been forced to provide employee housing. Older Vermonters are stuck in large homes that are expensive to maintain, socially isolating and physically unsafe for them. Homelessness has spiked.

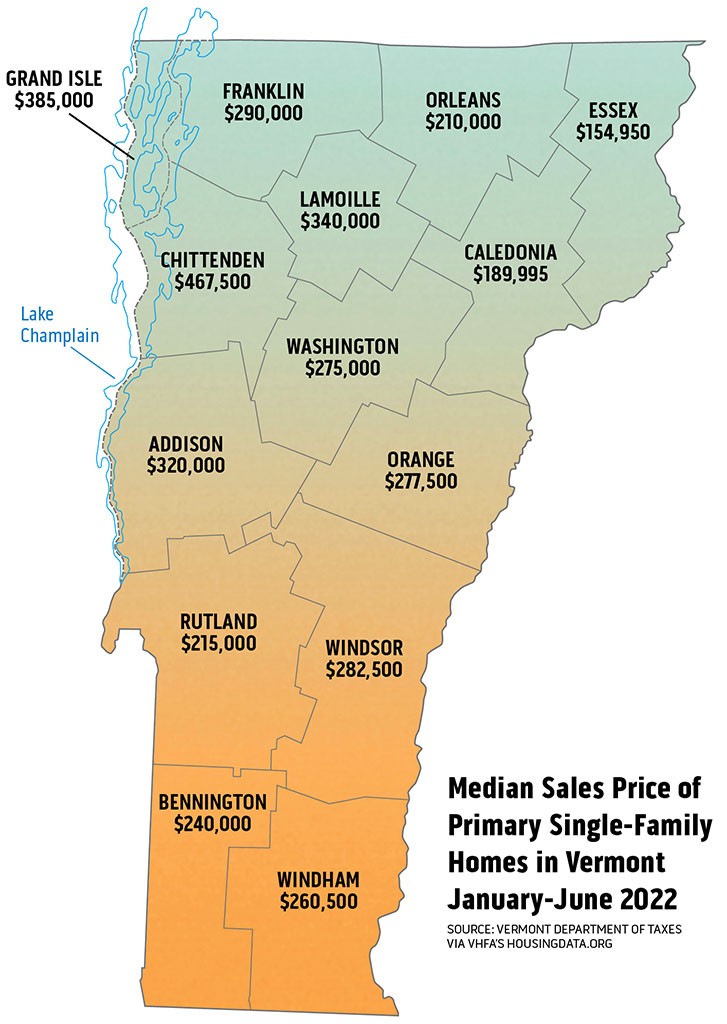

Sharply rising interest rates have slowed price increases, but most homes remain too costly even for families of average means to afford. The median price of a home in Vermont during the first half of 2022 was $295,000; in Chittenden County, it was $424,000, property tax records compiled by the Vermont Housing Finance Agency show. Nationally, home buyers between July 2021 and June 2022 skewed "older, whiter and wealthier" than at any point in at least a generation, the New York Times recently reported.

Looking for housing?

Are you having trouble finding affordable housing? Check out Seven Days' Vermont Housing Resources Guide, which lists public and private organizations that help qualifying Vermonters find shelter and rent, purchase and maintain homes.

While housing costs are subject to regional and national pressures, Vermonters have long viewed new development with skepticism. Residents are practiced at delaying, downsizing or banning denser development. The state's postcard vistas, quaint villages and single-family homes have been zealously guarded, but communities have been less committed to ensuring the availability of modest-priced housing in accessible neighborhoods. Even in Burlington, which requires new multifamily buildings to include some lower-cost units, prices have soared and class divides remain stark.

This final installment of the series examines how the housing crisis is forcing Vermonters to confront uncomfortable questions about the state's future. Without a path to affordable homeownership, an already small contingent of young Vermonters and residents of color is losing out on its best shot at financial security. The dynamic threatens to shape the character of Vermont cities and towns more than any change to their visual landscape.

"If we don't build a lot more housing and rehab a lot more housing," said Charlie Baker, executive director of the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission, "Vermont is going to become even more gentrified, as Vermonters can't afford to live here and we become the vacation paradise of New England."

Over the last couple of years, the state has dedicated unprecedented resources to create affordable housing, rehabilitate aging homes, pay rents for the unemployed and provide emergency shelter. More towns are exploring ways to build infrastructure and reviewing their zoning rules, with an eye toward making it possible to construct denser housing in village and town centers. Some nonprofits have launched programs to help BIPOC residents buy a home. Lawmakers are weighing a menu of demands, including tenant protections, continued state funding, regulatory changes and tax reform.

Altering the state's trajectory will require a long-term commitment and difficult choices. At the same time, cities and towns have plenty of space to accommodate more housing. Vermont has room to chart a more inclusive future, noted Rachel Batterson, who directs the Housing Discrimination Law Project at Vermont Legal Aid.

"We can build — at a scale that is appropriate to Vermont's various communities — housing affordable to a range of Vermonters," Batterson said, "so that Vermont does not look like the rest of the country, with poor people and people of color isolated in one section of town and other people living in other sections of town."

The 'Character of Jericho'

- James Buck

- Jericho Corners

In 1959, a classified ad in the Burlington Free Press featured a small, newly built country home in Jericho. The five-room ranch on Lafayette Drive, three-quarters of a mile down the road from Joe's Snack Bar, was offered for $14,500 — about $150,000 today.

Compact developments such as the one on Lafayette Drive, which featured lot sizes of less than half an acre, would soon become much more difficult to build in Jericho. The town selectboard passed zoning ordinances in 1961 that restricted lot sizes to at least half an acre. In a letter to taxpayers, members of the zoning committee said the new rules were designed to protect property values and preserve Jericho's "unspoiled villages" from "substandard buildings."

White-collar newcomers fueled a population jump from 1,400 in 1960 to 2,300 in 1970. Jericho's proximity to Burlington-area shopping centers and employers such as IBM, coupled with its rural scenery, made it an attractive place to live. By 1979, Jericho had become a wealthy "bedroom community," a revised town plan noted. The following year, home prices in Jericho trailed only Shelburne for the highest in Chittenden County, at $65,000.

Residents' biggest concerns? Strip malls and sprawl. The 1979 plan's stated "central purpose" was to control "the inroads of suburbia which threaten to change the existing character of Jericho."

The town accomplished its notion of "responsible growth" through strict land regulations, Lacy's research suggests. In 1981, the town established a residential district that required at least three acres per single-family home, and more for multifamily residences. Its village centers still required at least an acre for each home. The zoning board even assumed oversight of home occupations such as doll making, which required a permit.

By 1989, Jericho's town plan acknowledged that housing was no longer affordable to median earners. A small bump in new housing permits followed, only to decline steadily for the following 20 years, town data show.

That makes Jericho similar to many other communities. Lacy's citizen research illustrates the powerful role that municipalities have played in shaping today's housing patterns. Residents leverage land-use rules to restrict development, usually so it caters to their own tastes. The Connecticut Zoning Atlas, a first-of-its-kind project launched in 2021 that analyzed zoning rules in that state, found that 70 percent of Connecticut's primary residential districts only allowed construction of single-family dwellings without special permission.

"When you look at the practice of zoning, you realize some of that was really exclusionary," Baker, of the regional planning commission, said. "A bunch of white folks moved into a town and wanted to keep it like that."

The language in the old town plans colors how Lacy sees present-day debates about residential development. Dearly held values — preserving wildlife habitat, scenic views and town "character" — were also stated concerns in the midcentury town plans.

"We've invented a string of values that allow us to pursue our self-interest," he said.

Lately, Lacy has been driving his neighbors around town in an effort to convince others of the consequences of Jericho's historic land-use rules. He calls it "Chuck's zoning history tour." While touring with a selectboard member recently, Lacy said, he stopped at a small house with cars parked out front and knocked on the door. Lacy and his passenger met a young couple, he said, who told them they were paying more than $1,450 a month to rent a 400-square-foot apartment.

They were the kind of people who, 60 years ago, might have bought the home on Lafayette Drive.

'Out of Scale'

- James Buck

- The wooded lot off Route 7 in Shelburne where neighbors have opposed a planned apartment complex

Last month, members of Shelburne's Development Review Board considered a permit to build 78 units of multifamily housing on six wooded acres behind an office on busy, commercial Route 7.

After listening to a presentation by the developers, board members looked out at rows of residents and invited public comment. Bob Bouchard, one in a battalion of neighboring homeowners who objected to aspects of the project, was the first to step up to the microphone.

He wanted to talk about turkey vultures.

Seven Days wrote about the brewing conflict as part of the "Locked Out" series kickoff in March. Chiropractors Stephen Brandon and Shelley Crombach were then proposing to create more than 100 residential units, which was allowable within a zoning district the town adopted in 2016.

In the face of intense opposition, they'd since pared down their proposal and designated a portion of the proposed units for senior housing. Bouchard, however, who works as a development manager for Pizzagalli Properties, a real estate development and property management firm, still had concerns.

Turkey vultures are "not my favorite bird," Bouchard said to the board. But he asserted that the project threatened a nesting area for the "federally protected species."

In fact, the scavenger birds are not listed as an endangered species, the developers' wildlife consultant, Dori Barton, replied via teleconferencing, nor did she find in the patch of woods a significant turkey vulture habitat.

Shelburne, one of the richest towns in Vermont, also has some of its highest housing prices. In the first six months of 2022, 30 homes sold for a median price of $687,500. While new housing construction there has jumped in recent years, the battle playing out over the Crombach development shows how, despite soaring prices, some residents continue to fiercely resist denser development — at least when it's near their property.

Residents of the single-family-home neighborhoods adjacent to the Crombach project organized themselves under a banner called Shelburne Neighbors United for Responsible Growth. They created a website and hired a lawyer.

Such organizing by neighbors is typical when large projects are proposed in Vermont. The long-delayed CityPlace Burlington project, for instance, led to a yearslong lawsuit. Residents are exercising their rights when they speak out against a project or sue to block it, and some projects may in fact be too ambitious.

But builders, including those in the nonprofit housing sectors, identify local opposition as a high hurdle to completing projects. Last month, the Vermont Housing Finance Agency held a daylong conference to discuss issues affecting those trying to house struggling Vermonters. The next day, the state's for-profit developers took over the meeting space and had their own conference. Their goals and points of views were different, but the conferences shared a common theme: Vermonters need to stop fighting tooth and nail whenever a housing project is proposed.

The Shelburne Development Review Board had not issued its decision on the Crombach project by press time, but some neighbors have already vowed to appeal if it's approved. Meantime, they've notched a bigger win. Shelburne's selectboard unanimously voted to rescind a zoning overlay district that allowed dense residential developments such as this one in parts of the Route 7 corridor after a consultant told the town it was "overly complex" and vague.

SNURG supports new and more diverse housing in Shelburne, said Robilee Smith, a retired IBM manager who helps coordinate the group's work. On a recent drive around town, Smith pointed out other multifamily housing developments that she said haven't disrupted surrounding neighborhoods, such as a large assisted-living facility next to a mobile home park.

The proposed 78-unit complex next to Smith's house is a 10-minute drive from downtown Burlington, connected to water and sewer lines, and located next to a bus stop. But Smith considers it "out of scale."

Smith and her husband have occupied a beautifully maintained house on Wild Rose Circle for 28 years. "Having all those apartments staring in would certainly change the feelings here," she said from a small, sun-drenched addition with windows facing the wooded lot. "My sanctuary would no longer be the sanctuary."

Smith said the zoning district threatened to make the Route 7 corridor of Shelburne, with its surfeit of chain restaurants and car dealerships, look like Winooski, where three- and four-story apartment buildings line a small, walkable downtown. Smith asserted that larger apartment buildings like those in Winooski don't foster community. "A simple thing I can say is that, you know, you don't dare order something from Amazon, because your package will be stolen," she said.

A second citizen group, Shelburne Alliance for the Environment, recently formed in response to development pressures in town. Member Rowland Davis, who describes himself as a "climate warrior," said he wants to protect the town's "rural character" from "ticky-tacky boxes" — a reference to the 1960s suburban-satire lyric popularized by Pete Seeger. He argues that dense development outside Shelburne's village center would create high per-capita greenhouse gas emissions.

Based on its population, Davis said, Shelburne is already doing more than its share to meet a countywide campaign to build 3,750 market-rate housing units and 1,250 affordable units by 2025. More than 90 single-family homes and townhomes are being built on a former piece of the Kwiniaska Golf Club, and Champlain Housing Trust is redeveloping an emergency short-term shelter on Shelburne Road into nearly 100 affordable apartments and condos.

Some residents worry that too many people still can't afford to live in town.

"You need a diversity of people," said Pam Brangan, chair of Shelburne's housing subcommittee, which voted to support the Crombach project. "I feel like we're pricing out the younger families, the younger generation."

As Shelburne reconsiders its zoning rules, town manager Lee Krohn suggested that some residents may be too focused on what development they don't want to see.

"If I could wave a magic wand," he said, "I would ask us all to take a step back and do a clear job trying to gain consensus on what goals we're actually trying to achieve."

There is one big housing project in Shelburne that has not ginned up controversy. On the far side of Kwiniaska Golf Club, builders recently tore down a mansion on Governors Lane. In its place, on 53 acres of rolling meadows, an even grander house is under construction — one with five bedrooms, nine bathrooms and a seven-car garage. The place is designed to accommodate a "luxurious, yet relaxed living experience," a sales listing promises. The price: $10.8 million.

Moving Forward

Michael Arnold came to Burlington in 2013 as an undergraduate at the University of Vermont, where he's now pursuing a PhD in complex systems and data science. At age 28, he counts himself among the generation being "pushed out" by the housing crisis.

So Arnold and several others who met online decided to form their own citizen action committee. Vermonters for People-Oriented Places, as the nascent group dubbed itself, started meeting in Burlington's Fletcher Free Library and emailing local officials about public transit and zoning reform. The members want sustainable, affordable housing and transportation — a lot more of it.

"Who's gonna speak up for people's interest in having enough houses to start the next phase of their life?" Arnold said. "It kind of has to be us, right?"

Throughout the state, the void of reasonably priced housing is fueling action in ways Vermont hasn't seen in at least a generation. Residents are forming working groups to advocate for more permissive zoning and tenants' rights. Housing has risen to the top of the agenda for local officials and state lawmakers.

Driving the momentum has been an unprecedented pot of federal aid to fund land-use reform, infrastructure and housing development. Vermont Housing and Community Development Commissioner Josh Hanford is thinking about what will happen when the money's gone.

"My fear is," Hanford said, "we'll burn through all this money, have short-term success in seeing housing built, but we haven't actually changed the system."

Hanford's prescription: Treat "the right to develop housing" on par with agriculture, open space and historic villages.

Housing professionals broadly agree that addressing a chronic supply shortage must be an urgent priority. But the housing crisis extends beyond that, others say.

Homes also are increasingly commodified — a phenomenon that stretches far outside of Vermont. A United Nations special rapporteur called attention to the global trend in a 2017 report to the UN Human Rights Council, describing it as corrosive to the notion of housing as a human right.

Global hedge funds do not control Vermont's housing stock, but the lucrative market has led to a spate of apartment conversions, house flips, short-term rentals on sites such as Airbnb and tenant displacements. Adding more rental housing, on its own, isn't good enough, according to Scott Muller, a Montpelier-based environmental engineer and urbanization expert who has consulted with governments around the world on development.

Vermont's cities and towns should strive to create more opportunities for homeownership, as well as rental affordability and security, he said.

Winooski has struggled to achieve those goals despite taking steps to permit denser housing in parts of its square-mile downtown, Mayor Kristine Lott said.

"We need action at the state level," she said.

Activism around "just cause" eviction, which bars landlords from kicking out tenants without good reason, has expanded to more towns since Gov. Phil Scott vetoed a voter-approved charter change in Burlington in May. The measure is a basic protection that would provide tenants stability in an unbalanced rental market, Rights & Democracy organizer Tom Proctor said. In 2020, the Tenants Union of Brattleboro successfully lobbied the Brattleboro Selectboard to restrict the amount a landlord can charge for a security deposit. The Burlington City Council recently placed restrictions on short-term rentals.

State legislative leaders have said housing will be a priority when they convene in January. "It seems to be at the top of everyone's list," said Sen. Kesha Ram Hinsdale (D-Chittenden). They'll face decisions about what to do with programs that were funded through emergency COVID-19 aid and whether to compel zoning reform or tenant protections.

Second homes are likely to receive scrutiny at the Statehouse come January. Rep. Emilie Kornheiser (D-Brattleboro) said she wants to use her role as vice chair of the House Committee on Ways and Means to examine how Vermont's second homes, which often sit vacant for entire seasons, might be taxed at a higher rate.

Absentee homeowners are using precious housing stock, she said, and often don't contribute to communities in the same way as full-time residents.

"The very basis of Vermont's social infrastructure is based on volunteers and folks showing up for each other," Kornheiser said. "When we don't have that community diversity and folks who are able to spend time in their own communities, that really frays."

The Walls Come Down?

- James Buck

- SJ Dube

Jericho's most recent town plan, completed in 2020, articulates a goal that was absent from the plans of the '60s, '70s and '80s. Alongside protecting the environment and preserving "rural character," the current plan seeks to "promote socioeconomic and demographic diversity," in part by encouraging a wide range of housing in its village centers.

The goal, in part, recognizes a concerning trend. Jericho, like much of Vermont, is getting older; there are fewer kids, which led to the closure of an elementary school in 2019.

"We want to be inclusive, and we want to be able to bring young families into Jericho," McMains, the selectboard chair, said.

Over the past two years, the town has started to make changes to its zoning, planning commission chair Susan Bresee said. Minimum lots are smaller in some districts, and duplexes can be built anywhere a single-family home is currently allowed. Triplexes and fourplexes are allowed in more areas, too. The town is using a state grant to study a village wastewater system, which would enable high-density development.

During the pandemic, the town also formed an affordable housing committee. SJ Dube, a mother of two who moved to Jericho in 2013, signed up to be its volunteer chair. She didn't bring a particular expertise in housing policy, but she was concerned about issues of equity and saw in housing "a real need to wrestle with those kinds of questions."

In the months that followed, Dube and others on the committee looked into data on the town's housing trends, which she and Bresee presented to town officials in August.

They found that the pace of housing construction in Jericho has doubled over the past few years but has been limited to large, expensive single-family homes. The cost to buy a home in Jericho is higher than what a pair of Mount Mansfield Unified Union School District teachers could afford.

Dube's conclusion: The situation won't improve without further intervention.

She, Bresee and others are working on initial ideas, which will be sent to the selectboard in coming months. The town has just shy of $1.5 million in pandemic relief money that the planning commission recommended be earmarked for housing "inducements," Bresee said. It could also start setting specific housing goals.

The hardest work is ahead, which is why Dube said she's thinking a lot about how to talk about the subject with her neighbors. What would more housing look like? What might need to change "in order to make the town more equitable and an accessible place to live?"

"Honestly," Dube said, "a lot of those interventions will take Jericho in a direction that it's never really gone before — at least, not in the last 40 years."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.