Throughout the fall, Republican gubernatorial candidate Scott Milne repeatedly claimed he'd be the first challenger to topple an incumbent Vermont governor since Phil Hoff pulled it off in 1962.

On Election Day, he came remarkably close.

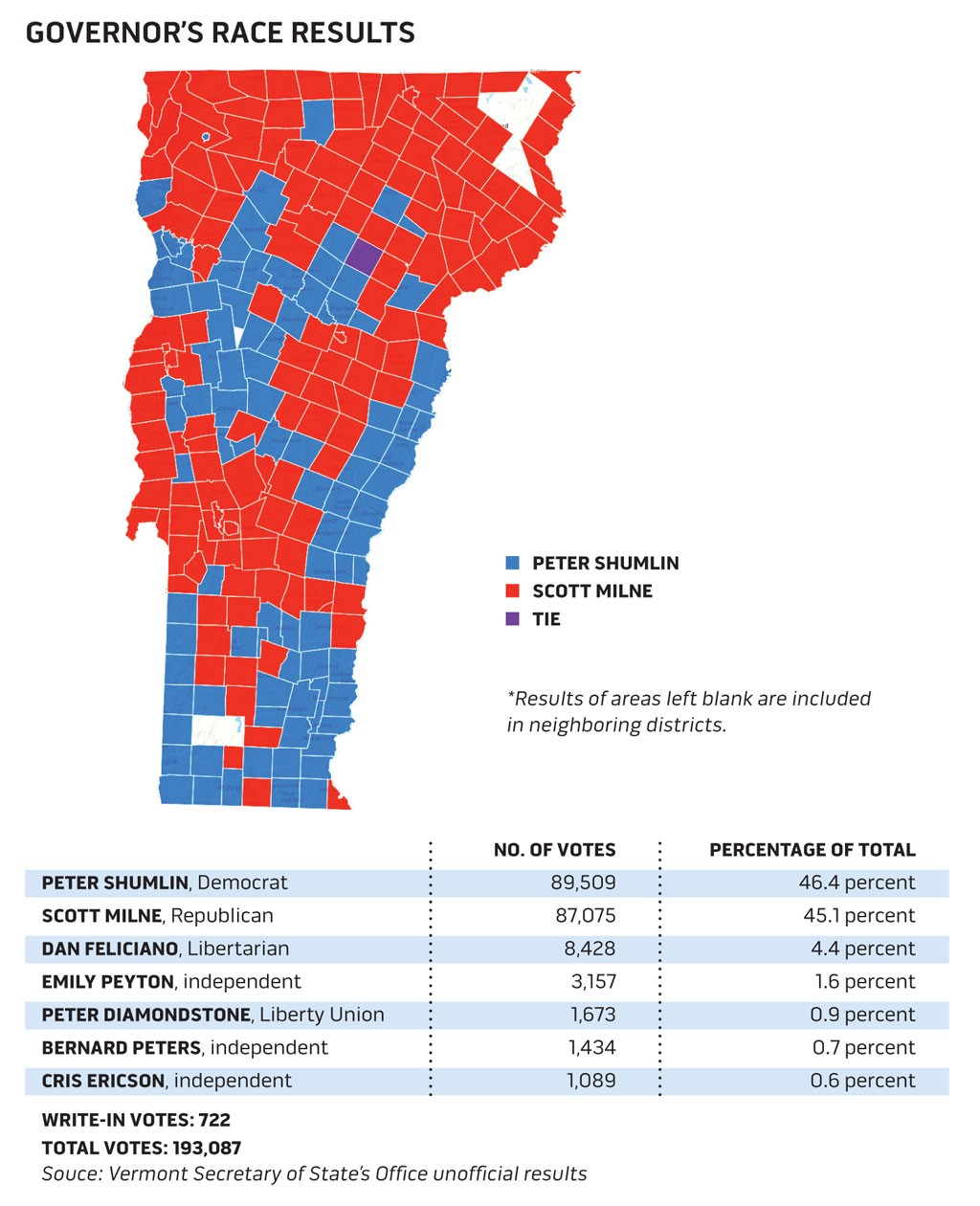

According to uncertified results from the Secretary of State's Office, Milne came within 2,434 votes of besting two-term Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin. The incumbent won 89,509 votes, or 46.4 percent, while the challenger took 87,075 votes, or 45.1 percent.

Since neither candidate cleared the 50 percent threshold, the race will be settled next January by the 180 members of the Vermont House and Senate, who will select a governor by secret ballot from among the top three vote-getters.

The last time an incumbent governor found herself at the mercy of the legislature was in 1986, when first-term Democrat Madeleine Kunin won 47 percent of the vote, compared with Republican lieutenant governor Peter Smith's 38.2 percent. Keeping Kunin from a majority that year was a challenge from the left: Burlington mayor Bernie Sanders took 14.4 percent of the vote.

Milne's near-plurality this year is all the more remarkable given that the closest thing to a spoiler was Libertarian Dan Feliciano, a conservative who likely drew more support from Milne's base than from Shumlin's. If Milne took even half of Feliciano's 8,428 votes, the Republican would have won a plurality.

So how did Shumlin come so close to losing?

It's impossible to divine demographic data from Tuesday's election returns, but it is possible to parse geographical trends, since each of the state's 275 polling places reports its results separately. In Vermont, most such precincts correspond to the state's 255 towns and cities, but some larger municipalities are broken into multiple precincts. Burlington, for example, includes seven of them.

Milne drew support from a broad geographical range, winning a plurality in 162 precincts, while Shumlin did so in just 112 (the candidates tied in Woodbury). That's not unusual, given that Republican candidates tend to do better in Vermont's rural, less populated municipalities, while Democrats perform better in denser towns and cities.

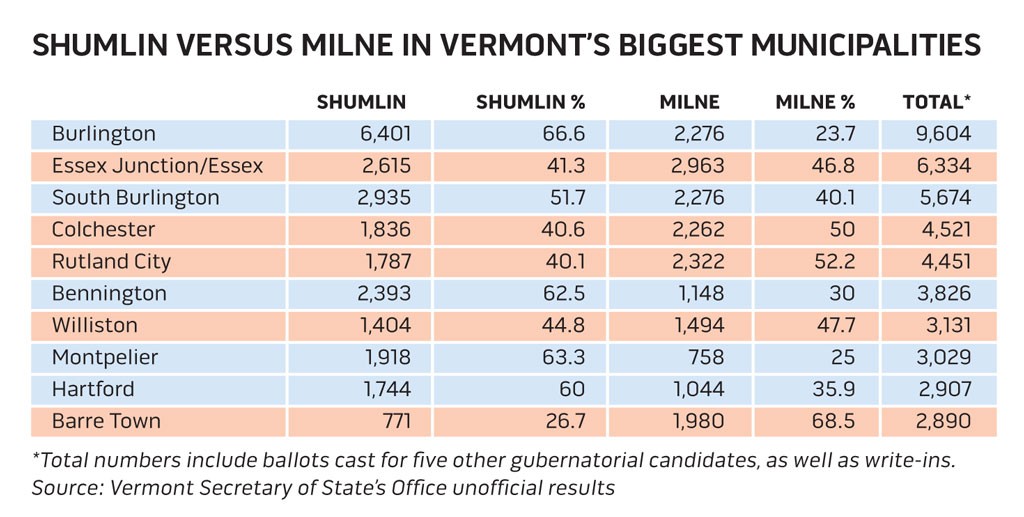

More surprising is how well Milne did in Vermont's population centers. Shumlin won the big kahuna — Burlington's 9,604 gubernatorial voters — by a 66 percent to 23 percent margin, and he also won South Burlington. But Milne came away with more votes in three of the state's other five top-voting municipalities: Essex, Colchester and Rutland City.

In fact, Milne won 10 of Vermont's 20 top-turnout towns and cities — including Williston, Barre Town, Milton and Barre City. Shumlin, meanwhile, took Bennington, Montpelier, Hartford and Middlebury.

Another way to look at it is through the lens of Vermont's 13 Senate districts, which align roughly with the state's 14 counties (Essex and Orleans counties share a district). Of those, Milne won eight, while Shumlin won five.

Shumlin posted big numbers in liberal Chittenden and Windham counties, but he got crushed in moderate Franklin and Rutland counties. The latter two featured a host of competitive House and Senate races, which may have bolstered turnout there.

More distressingly for Shumlin: He came out 100 votes short in Washington County, which tends to vote for Democrats, but is home turf to Milne and his well-connected family. As liberal pundit John Walters noted on his Vermont Political Observer blog, Democratic and Progressive senate candidates won hard-fought contests in Washington and Orange counties, while Shumlin lost both.

In fact, the incumbent's margin of victory was so slim that he won more votes than just four of the Senate's 30 members in their respective districts. Of those he outperformed — Windham's Becca Balint, Bennington's Brian Campion, and Chittenden's Michael Sirotkin and David Zuckerman — only the last had previously run for countywide office.

The most important number in the 2014 gubernatorial race was 43.6. That's the percentage of Vermont's 443,400 registered voters who actually cast a ballot — a record low.

In liberal Vermont, Democrats tend to do better when presidential or U.S. Senate races drive broad voter turnout. This year, the only contest to draw any excitement at all was that for lieutenant governor — a largely ceremonial position.

Though Milne came closer to defeating Shumlin than either of the incumbent's previous Republican foes — Brian Dubie in 2010 and Randy Brock in 2012 — Milne won fewer raw votes than either of his predecessors. Dubie took 115,212 votes, Brock 110,940 and Milne just 87,075.

The drop-off was far steeper for Shumlin. Two years ago, when he shared the ballot with President Barack Obama and Senator Bernie Sanders, the governor won 170,749 votes. This year, he won barely more than half that: 89,509.

Across the board, Democrats felt the effects of Vermont's historically low turnout. Running against Republican Mark Donka, the same opponent he faced two years ago, Congressman Peter Welch (D-Vt.) dropped more than 7 percentage points this time around, to 64.4 percent.

But Welch, who shares Shumlin's center-left politics, won 33,840 more votes than the governor. How to explain that — and, more broadly, the governor's dismal performance?

In recent days, Seven Days spoke with nearly a dozen Vermont politicos to solicit their theories. Most — particularly Democrats close to the Shumlin administration — declined to speak on the record. We sifted their ideas into seven buckets:

The Base Problem

One reason Democrats didn't turn out? Many have soured on Shumlin, who won a competitive primary in 2010 by pushing liberal issues — including legalizing gay marriage and shutting down Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant — but has since tacked to the center.

Democrats such as Bakersfield activist Euan Bear showed up to the polls but refused to vote for Shumlin.

"People who would otherwise vote pretty much a straight ticket made a point of saying to me, 'Except for Gov. Shumlin,'" says Bear, who serves as a state committeewoman for the Vermont Democratic Party.

Among the factors that alienated the base? Shumlin's public firing of liberal icon Doug Racine; his support for Vermont Gas' pipeline extension; his 2013 legislative focus on welfare reform and skepticism over whether he'll follow through on enacting single-payer health care reform.

The Independent Problem

One of the more interesting findings of a Castleton Polling Institute survey completed a month before the election was that more independents disapproved of Shumlin's performance than approved of it.

Why? It's impossible to say for sure, but two issues likely played a role: rapidly rising property taxes and health care reform. Regarding the latter, independents were likely upset about Vermont Health Connect's continuing performance issues and uncertain about Shumlin's single-payer ambitions.

"To this day, we don't know what it is," Sen. Dick Mazza (D-Grand Isle), a moderate Democrat, says of single-payer. "People were very fearful of what would happen."

Shumlin's Competence Problem

Shumlin has long touted his ability to "get tough things done." But for the past year, his administration has struggled to get Vermont Health Connect operating as advertised.

Whether or not it's fair to pin Obamacare's woes on Vermont's governor, months of negative media coverage surely eroded public confidence in Shumlin — and ate into his vote totals.

"I don't think it's a repudiation of the vision Shumlin and others have laid out," says Rep. Chris Pearson (P-Burlington). "I think it's a comment on the execution, which has been less than stellar."

Milne's Competence Problem

Ironically, Milne's lack of electoral experience, difficulty debating, inability to raise money and green campaign staff may have helped him in the end. Because reporters and pundits didn't take him seriously, passive Democrats saw no reason to get motivated. Others felt free to cast a protest vote for Milne, Feliciano or the four other candidates in the race.

Insiders say Shumlin's campaign recognized the threat in September, which prompted it to spend heavily on television advertising earlier than expected. But the campaign couldn't truly sound the alarm, lest it motivate Vermont Republicans to unite around Milne or outside groups to invest in his campaign.

It's tempting to say that a more experienced or better-funded opponent — such as Brock, Lt. Gov. Phil Scott, Rep. Heidi Scheuermann (R-Stowe) or retired banker Bruce Lisman — could have outperformed Milne. But if any of them had gotten into the race, Shumlin and his Democratic allies would have stepped up their game.

Feliciano Hype

Conversely, Feliciano appeared to be a more natural campaigner and more polished debater than Milne. An early burst of support from conservative Republicans gave him credibility with the press, as did the imprimatur of pro bono campaign manager Darcie Johnston.

Many political observers expected Shumlin to come in under 50 percent, but they figured Feliciano would consume a bigger slice of the conservative pie, leaving the race safely in Shumlin's hands.

They were wrong. Feliciano won 10 percent of the vote in his hometown of Essex and did well in a handful of other northwestern towns, but he barely registered in the state's four southernmost counties. In the end, he won just 4.4 percent statewide.

That means Shumlin-haters either felt more comfortable voting for a Republican or were more attracted to Milne's comparatively moderate message.

The Likability Problem

There's a reason Shumlin himself was never featured in any of his own TV ads, while Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) was. After four years as governor and two decades in the legislature, Shumlin appears to have developed an unfavorable personal reputation outside of Montpelier.

One factor that may have played a bigger role than anticipated was last summer's controversy over a land deal between Shumlin and an East Montpelier neighbor. The governor's frequent out-of-state travels probably didn't help, either. Milne never stopped hammering him about that.

National Headwinds

Vermont politics don't operate in a vacuum. The same national headwinds that hurt Democratic gubernatorial candidates throughout the country probably blew into Vermont, too.

Throughout the country, voters appeared frustrated with the slow pace of the economic recovery. Here in Vermont, those struggling with a growing affordability crisis may have been looking for someone to blame. And in a low-turnout election, it's the angriest voters who show up at the polls.

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.