- Courtesy of CRREL

- Testing snow guns at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory

Donald Perovich seems too motivated to spend an entire year drifting aimlessly. But that's exactly what the research geophysicist did starting in October 1997, when he and a team of international scientists boarded the Des Groseilliers and deliberately trapped the vessel in Arctic sea ice. Their mission: to observe firsthand how global warming affects the ebb and flow of the polar ice cap.

"Wherever the ice went, that's where we went," recalls Perovich about the $19.5 million SHEBA project — short for Surface Heat Budget of the Arctic Ocean — which took the ship more than 1,000 miles from its original location. "We were able to get a full year's cycle of how the ice grew in the winter and how it melted in the summer. It was awesome!"

These days, 64-year-old Perovich spends less time on ice floes than he once did. But after nearly three decades as a researcher with the Army Corps of Engineers' Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, N.H., he still exudes a childlike fascination with the Arctic's harsh yet beautiful environment. And he returns whenever he can. As he puts it, "I'll keep going back as long as I've got game."

Because Perovich is widely recognized as an international expert on the interaction of solar radiation and sea ice, his research is highly sought after by climate-change scientists. These days, much of his work takes place on CRREL's 30-acre campus along the Connecticut River, just up the road from Dartmouth College, where he also teaches.

Despite its location this far south of the Arctic Circle, CRREL is home to the coldest spots in all of New England. The research complex includes 26 deep-cold rooms that range in size from a 10-by-12-foot laboratory that can maintain minus-40 degrees Fahrenheit to the airplane-hangar-size Frost Effects Research Facility, the largest refrigerated warehouse in the United States.

For more than 50 years, researchers from the U.S. military, colleges and universities, governmental agencies, and private industry have come to CRREL to perform experiments in its cold-weather tanks, water flumes and test basins. Here, scientists and engineers can recreate land, river or ocean scenarios, test hypotheses and solve problems unique to icy and snowy conditions.

Military and civilian engineers alike use these labs to prototype new products and equipment such as snow tires, oil-spill cleanup equipment, ground-penetrating radar and specialized concrete used in subzero climates. Though technically a U.S. Army installation, CRREL receives the bulk of its funding from the National Science Foundation, which enables it to work with both military and civilian entities.

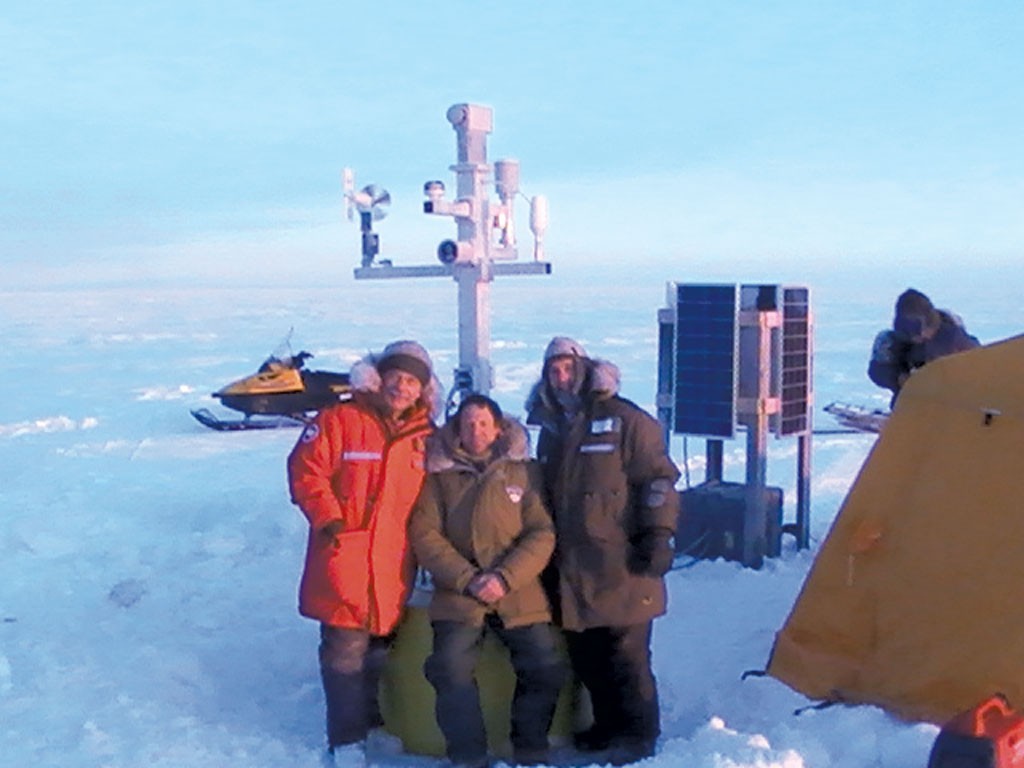

- Chris Williams (center) with CRREL team deploying

Currently, about 250 people work at the Hanover facility, including 140 scientists, researchers and engineers. The lab maintains the central database for the nation's system of locks and canals; there's even a daycare facility on-site. Outside of Hanover, CRREL runs low-temperature laboratories and field offices in Anchorage and Fairbanks, Alaska, as well as a 133-acre permafrost research tunnel in Fox, Alaska, which contains climate information dating back 40,000 years.

From the outside, CRREL's cluster of '60s-era brick buildings looks no different from any industrial complex, except for the high-security guardhouse and wrought-iron fence, both of which were added post-9/11.

Inside, the lobby is decorated with large photos showing CRREL researchers on Mount Washington, at a military firing range in Alaska and on glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica. Walking through the facility's halls and offices, a visitor soon notices an abundance of "penguin crossing" signs. There are photos of polar bears and of CRREL staffers, dressed in bulky parkas, standing in front of snowmobiles, helicopters and icebergs.

Much of the research conducted at CRREL in recent years has focused on climate change. On a recent weekday in a humming, windowless machine shop, Perovich stands in front of a long, metallic tube containing a tangle of electronic components — the innards of what will soon become an Arctic research buoy. As he explains, "The best thing is being there, but the next best thing is these buoys."

Standing beside Perovich is Chris Williams. If Perovich is CRREL's Mr. Spock, conjuring up the scientific theories that explain how retreating sea ice is both a harbinger and amplifier of climate change, Williams is its Scotty. He's the nut-and-bolts electrical engineer who assembles, deploys and maintains the network of research buoys that are scattered throughout the Arctic.

The buoy before us, which Williams and his team are assembling, is called an ice mass balance buoy. Its job will be to measure, record and radio back data on the depth of the snow, the thickness of the ice and the temperature of the seawater. (All those data, as well as live-streaming webcam video, are free and available to anyone online.)

An even larger buoy called an ozone buoy, or O buoy, monitors atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, ozone and hypobromite. Each buoy is unique, Williams explains, and is built to accommodate the specific parameters of whichever new study is being undertaken.

A 25-year veteran of CRREL, Williams is also one of its few researchers who have visited both the North and South poles. He prefers the South Pole, he says, as there's more to look at and better living facilities, including hot showers. When visiting the North Pole, he adds, "You take a lot of baby wipes with you."

As a seasoned polar veteran, Williams also knows a thing or two about constructing equipment that can withstand those punishing environments. The prototyping, which is all done at CRREL's New Hampshire facility, is crucial work, as each ice mass balance buoy costs $20,000; an O buoy, $250,000.

"It's very disappointing," Williams says, "when you put a lot of effort into one and it dies after a week because a pressure ridge snapped it in half or a polar bear damaged it."

Fortunately, most of Williams' buoys survive much longer, reporting back data for years at a time before they're eventually destroyed or lost at sea. In fact, on the day of my visit, Williams had just received an old buoy found by the Canadian Coast Guard — the first time he's ever recovered one whole. Lying on the concrete floor, it is still in near-pristine condition.

When you're talking with someone who has visited the polar regions repeatedly over decades and witnessed their changes firsthand, it's impossible to avoid the question: Do you believe climate change is caused by human activity? For his part, Williams doesn't wade into such debates, at least not publicly. His efforts, he says, are "driven by our interest in ice. I don't get involved in that stuff."

Not all the work at CRREL delves into such weighty issues as the survival of the human species. As my guide, public affairs director Bryan Armbrust, points out when we visit other buildings in the complex, many of CRREL's projects are more mundane. They include research conducted by the U.S. Department of Transportation in Minnesota and Wisconsin on ways to prevent potholes from forming. Another study looked at the best pitch for roofs in northern latitudes to maximize solar warmth and prevent them from caving under snow loads.

We visit one cold-weather test basin that's about the length of two Olympic swimming pools. Here, Armbrust explains, CRREL researchers worked with engineers from Vermont to devise a cost-effective method for breaking up ice jams that float down the Connecticut River before they can take out bridge abutments in White River Junction.

In an adjacent cold-weather room, earlier this year, CRREL staffers created indoor blizzards that allowed R&D engineers from John Deere to prototype their new snow blower for the 2014-15 season.

In yet another room, CRREL staffers have been working with the U.S. Navy to devise submarine propulsion systems for use beneath polar ice. That room holds a slight whiff of ammonia, which, Armburst explains, is used as a refrigerant. Outside the towering refrigerator doors sit enormous white sacks of salt, used for creating seawater.

From there, we walk downhill to the largest building on the campus: the Frost Effects Research Facility, or FERF. This 29,000-square-foot freezer/warehouse is used for full-scale replication of surfaces, such as highways and runways, under subfreezing conditions. When the U.S. military wanted to land its largest cargo plane, the C-17 Globemaster III, in Antarctica, CRREL used this warehouse for developing the Pegasus Field ice runway near McMurdo Station.

"If you give us six months of research," Armbrust says, "we'll give you 20 years' worth of data."

Indeed, much of the data CRREL staff gather after just weeks in the field spark years of subsequent inquiries upon their return. As Perovich recalls, he was doing a field experiment a couple of years ago to test a hypothesis: If there's more open water in the Arctic, then there should be more sunlight and thus more phytoplankton. If it's still covered with ice, there should be fewer phytoplankton.

When Perovich got to the Arctic, however, he discovered something he hadn't expected: The ice was thin enough to allow the sunlight to pass through it, creating enormous ocean blooms below the ice.

"You go off in the field and see something like that, you've got enough to think about for a year or two," he says. "You can theorize all you want, but nature always has some surprises in store."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.