- Matthew Thorsen

- Meg and Peter Walker

In 1964, two natives of Scotland, both graduates of the Edinburgh College of Art, met in Vermont. Meg Brannan, who was studying fine-metals jewelry design and tapestry weaving at the time, was visiting her sister and brother-in-law. The latter was Ian Tyndall, a partner in the renowned modernist landscape architecture firm of Dan Kiley, based in Charlotte. Tyndall introduced Meg to the man who would become her husband: Peter Ker Walker. Also a partner in the firm, Walker had studied architecture at Edinburgh and landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Matthew Thorsen

Half a century later, the Walkers still live in Charlotte, in a 19th-century house in a clearing in the woods. From the soaring, two-story kitchen and living area that Peter designed, the couple's shared studio barn is visible through a wall of windows. On a recent visit, the only sound besides conversation is birdsong. With the couple's slightly muted Scottish accents and understated humor, even the conversation is quiet.

That quiet belies the international influence of Peter Walker's designs. "He's right at the top of the game, and has been forever," comments Idaho-based architect and frequent collaborator Jack Smith, also a former designer with Kiley. Walker's lack of a website makes Smith chuckle. "He's the legacy for Kiley; he's world-class. But he's so quiet about it all. He doesn't really know how to market himself, and he doesn't care."

Over their past half century in the Green Mountains, Meg and Peter Walker have developed singular careers while raising two children and, in Meg's case, teaching and working at the University of Vermont, Goddard College and Shelburne Museum. Today, each continues to pursue new creative challenges, despite having plenty of laurels on which to rest.

Some of Peter's designs during his time with Kiley became iconic in the world of landscape architecture. After he left to create his own firm in 1986, his projects included a marketplace in Osaka, Japan; an urban-parks system in New Haven, Conn.; and designs for the Seattle and southern France residences of a prestigious private client. The 79-year-old's latest projects are proposals for the environs of yet-to-be-built aquariums in Alexandria, Egypt, and Boulogne-sur-Mer, France.

- Matthew Thorsen

Meg Walker, meanwhile, became a sculptor with a conceptual bent. She also does drawings and watercolors — and, unlike her husband, maintains a detailed website. Now 71, the artist has devoted years to focusing on single subjects, which she whimsically summarizes on her site as "birds," "barns" and "brains." Since her first solo exhibit, in 1974 at the University of Vermont's Fleming Museum, Meg has shown at venues around the state, as well as in her native Scotland and in Brittany, France. Between 2004 and 2009, she exhibited annually at A.I.R. Gallery in New York City, the country's first women-specific gallery.

Meg is currently preparing for a two-person exhibit, titled "Brain Unraveled," at the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Hampden Gallery, opening September 13. Wearing a black vest that complements her short haircut, she points to several pieces intended for that exhibit that currently reside in the couple's house. One, called "Brain Storm," is a white plaster and papier-mâché ball the size of a large human head, mounted off center on a pillar base that contains a sensor and speakers. A viewer's approach activates a birdsong recording, while a small opening in the "brain" reveals a multicolored LED light.

When pressed, Meg offers general comments about her work. "I crunched up a newspaper, and this bird form appeared," she says almost nonchalantly of a piece from her "birds" phase, first shown at UVM's Colburn Gallery in 1993. Of her process, she merely says, "I've spent my life looking."

She's more specific in artist statements, such as the one for the Hampden Gallery exhibit. "The goal is to make real the intangible, unnamed, unformed images and ideas always skittering in and out of my consciousness ... The objective is to entice the viewer to take a closer look, to actively and mentally engage in the work."

Hampden curator Anne LaPrade Seuthe describes Meg Walker's work as fearless — a word nearly everyone interviewed for this story used. From crushed newspaper and other used and found materials, Meg leapt to metal sculpture in her "barns" phase, employing a local blacksmith to give her creations form. Her current "brains" phase draws on electronic devices and fiber optics, with the help of a German electrical engineer. "I love that kind of curiosity," Seuthe says.

Photographer and curator Terry Gips met Meg in 1976 at the first meeting Gips organized of the Vermont chapter of the Women's Caucus for Art, a nationwide initiative. "What really intrigues me [about her work] is a kind of inventiveness," Gips says from her house in Cape Cod. She recalls a piece that Meg created out of "tufts of sheep's wool left on fences" that she had collected in Scotland.

At an early exhibit called "Domestic Landscapes," at the Southern Vermont Arts Center in Manchester, Meg showed a work consisting of what she recalls as "these gorgeous pieces" of lint she'd collected from the dryer.

"That was a nice feminist touch," says Burlington sculptor Barbara Zucker, a longtime friend and fellow sculptor whose husband, architect Louis Mannie Lionni, shared a Church Street office with Peter for many years after the latter established his practice.

Yet, Zucker adds, Meg isn't necessarily, or only, a feminist artist: "I don't think she belongs to any group — her work is pretty singular." Even Meg's "brains" work of the past seven or so years, Zucker says, is a "big departure" from what she had done before. "She's trying to give substance to something none of us understands."

While Meg describes all her work as "about the landscape," including the "landscape of the mind," Peter intervenes directly in material landscapes. The Walkers' yard, an ordinary-looking stretch of mown grass, is not an example of his work — neither spouse is particularly interested in gardening these days. But when he's on the job, Peter creates planned landscapes, using built structures and plantings to control the flow of people through defined areas.

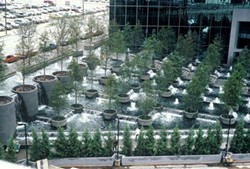

- Peter Ker Walker's Work: Oakland Museum, CA

Standing at a table in the studio barn, into which he moved his practice last year, the landscape architect pages through a portfolio of selections from his life's work and offers a reporter the occasional wry commentary. One of his projects was a Springfield, Mass., urban park that now gets little use owing to "this goddamn interstate," Peter says, pointing out the offending structure on the master plan. About a residence in the Northwest, he comments that one decorative Japanese bridge "cost more than a Volkswagen."

- Peter Ker Walker's Work: Fountain Place, Dallas TX

Much of Peter's work has a formal quality. He shares Kiley's affinity for the formal gardens of 17th-century French landscape architect André Le Nôtre, from whom Kiley derived his signature grids and allées of trees. Peter has used such elements in projects of his own, including the grid of large palm trees defining the entrance to the U.S. Embassy in Amman, Jordan. But he also mixes those fixed elements with informal spaces to allow for less structured interaction. "What we're doing is making external rooms," says the landscape architect. "The goal is to find the appropriate spaces for outdoor living."

- Peter Ker Walker's Work: La Defanse, Paris, France

Peter's renderings are stunning. "I'm not computer literate, so everything's done with pencil," he admits. "It's all schematics done in freehand until the CAD [computer-aided design] stage, and I farm that out." More evidence of his artistic ability lines the stairway to the studio's upper floor: framed sketches from his many trips around the globe, including a partly watercolor view of Eero Saarinen's famous St. Louis Arch. (Kiley's firm designed its park.)

Peter says he left Kiley after 24 years because "I was the quarterback, and he sensed I was beginning to spread my wings." As Boston-based architect Peter Chermayeff observes, Peter was in a "secondary position to Dan Kiley, but he was the primary person" on many major projects that bear Kiley's name.

Chermayeff met Peter in the 1970s and first collaborated with him on the Osaka aquarium and plaza, which opened in 1990. The two continue to work together; recent projects include the Alexandria aquarium they designed five years ago, which didn't get built because the Arab Spring intervened.

"What I enjoy about Peter is his way of complementing and enriching an architectural idea that comes from our side, which he then takes to another level," says Chermayeff. "He reinforces something that we've initiated rather than treating them [building and landscape] separately." The architect adds that Peter is "not preoccupied with his own [stylistic] vocabulary. He's more inclined to search for the right solution."

Chermayeff describes Peter as "modest on the one hand" — he's "under-marketed," opines the architect — "and on the other quite strong-minded." Says frequent collaborator Smith, "We've been together for 40-plus years; he can read my mind." Those close working relationships continue to generate commissions and recommendations. At the time of this writing, Chermayeff's partner was recommending Peter to do a site of "several hundred acres in the Boston area."

While Peter works out how the public can use a physical site, Meg continues to prod the imagination on her side of the Walkers' studio barn. A kind of parallel play characterizes this couple's creative lives. If their paths ever intersect, that meeting is suggested in a work of Meg's, a vitrine containing a dozen or so tiny white heads, each bearing a different expression on its plaster face. The piece invites interaction — guesses as to what these little figures are feeling and thinking. Like Peter's landscapes, it's a creation that exists for viewers to explore.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.