- Courtesy Of MMFA/Buffalo Akg Art Museum

- Photo of Marisol by Hans Namuth

There's a party going on in Montréal where celebrities, hipsters and regular folks are brushing elbows with stuffed dolls, giant babies and menacing sea creatures. No, it's not a Halloween parade. It's the inventive, surprising and revelatory world of artist Marisol (1930-2016), on view at the Museum of Fine Arts.

"Marisol: A Retrospective," featuring sculptures, masks and works on paper, tracks the 50-plus-year career of an artist whose work was variously concerned with motherhood, environmental decay, persona and sexual violence. Though well regarded in her time — her popularity peaked in the 1960s — Marisol isn't an unearthed gem but a neglected master.

The major touring exhibition was organized by New York's newly refurbished Buffalo AKG Art Museum (formerly the Albright-Knox Art Gallery). Marisol bequeathed her estate to AKG because it was the first museum to buy her work.

Expertly curated by AKG's chief curator Cathleen Chaffee — who also wrote an accompanying monograph — the 250-piece retrospective is a comprehensive celebration that leaves the viewer hungry for more.

Born Maria Sol Escobar in Paris, Marisol was the second of two children in a wealthy Venezuelan family. She spent most of her childhood shuttling between the U.S. and Caracas. "We traveled not because of business but out of boredom," she later told art critic John Gruen.

Marisol was 11 when her mother died by suicide, a trauma that caused her to cease talking. "I didn't want to sound the way other people did," she said in a 1975 interview with People magazine. By her late twenties, she did begin to speak again but said, "Silence had become such a habit that I really had nothing to say to anybody."

- Courtesy Of MMFA/Buffalo Akg Art Museum

- "John, Washington & Emily Roebling Crossing the Brooklyn Bridge for the First Time" by Marisol

Afforded the privilege to not have to work, Marisol nevertheless arrived in New York City in 1951 as a hungry, dedicated student. Having studied in Los Angeles and Paris, she immersed herself in courses at the Arts Students League and the Brooklyn Museum, as well as with famed abstract-expressionist painter and teacher Hans Hofmann.

"I can never remember a time when I wasn't drawing," she said, referring to her childhood in a 1965 New York Times Magazine profile.

Marisol indulged in the bohemian life, which included smoking a lot of weed. She cut a memorable figure. The artist once went to a party wearing a mask; after being goaded to take it off, she did so only to reveal a second mask.

By 1954, Marisol began making sculpture, working in bronze and terra-cotta and then wood. Raw and funky, with pre-Columbian and folk-art influences, her sculptures possessed a quality not always valued in the art world: They were funny — and not by accident.

"It started as a kind of rebellion," Marisol said in the Times Magazine story. "Everything was so serious. I was very sad myself and the people I met were so depressing. I started doing something funny so that I would become happier — and it worked. I was also convinced that everyone would like my work because I had so much fun doing it. They did."

But along with early recognition came apprehension. Shortly after her first gallery show, at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City, Marisol moved to Rome for nearly two years. When she returned, it was with renewed clarity and direction: Her subject would be herself.

Because of her physical beauty, introversion and nationality, Marisol attracted outsize media attention. Magazines labeled her "exotic" and "the Latin Garbo." In response, Marisol turned her creative attention on the viewer's gaze. There she is in sculptures, drawings and photographs, stone-faced or smiling, coolly looking at us looking at her.

And yet Marisol had no interest in being a brand. She's considered a pop artist, but, like Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, she defies categorization. Marisol's art feels lived in, ripe with imperfections and ghost drawings; it's anything but slick. Leaving one side of her affectionate 1962-63 sculpture "Andy" — a four-sided portrait of her friend Andy Warhol — seemingly unfinished allows viewers to fill in the space.

Marisol's shows in the '60s attracted crowds, but she was increasingly unsettled by the political violence and unrest in the U.S. In June 1968, Warhol was shot just three days before Robert Kennedy's assassination. Though the artist survived, Marisol decided that, again, it was time to bolt.

She traveled extensively in the Far East, learned to scuba dive in Tahiti and embarked on a series of fish sculptures made of wood. Polished and sleek, their faces (all Marisol's) are ferocious and horrible. These strange portraits — including one that looks ripped out of Creature From the Black Lagoon — have their own room in the exhibition.

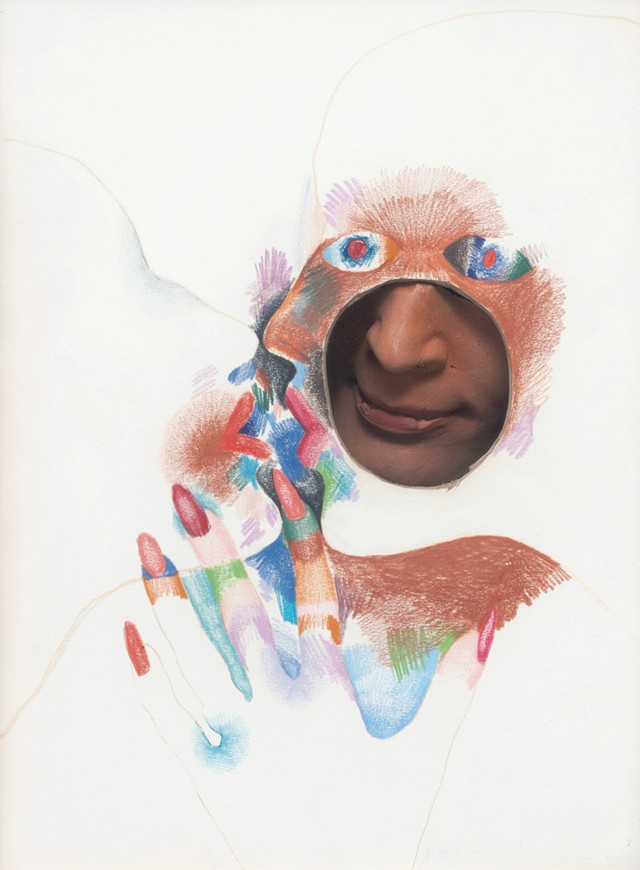

- Courtesy Of MMFA/Abrams Family Collection/bill Jacobson Studio

- "Face Behind a Mask" by Marisol

When Marisol exhibited her new work at New York's Sidney Janis Gallery in 1973, critics frowned and then yawned. "Now, maybe I've become paranoid," Marisol said in an interview at the time, "but it seems to me that in the '60s the men did not feel threatened by me. They thought I was cute and spooky, but they didn't take my art so seriously. Now, they take my art more seriously but they don't like me so much."

During this period, Marisol also made a series of huge drawings that depicted sexual yearning and brutality. Her masks grew more sinister; the threat of violence is palpable in a pair of wickedly designed brass knuckles. "I am not working for the general public anymore," she said in the mid-'70s. "I lost interest."

No longer a darling of the art scene, Marisol pressed ahead undeterred, designing sets for a number of dance companies, particularly Martha Graham's, and constructing large public installations in the U.S. and abroad. She worked alone, without assistants.

Marisol exhibited regularly in the '80s and '90s. The sculptures, including brilliant portraits of Georgia O'Keeffe, bishop Desmond Tutu and Pablo Picasso, echoed the eros and humor of her earlier work but were rendered with greater assurance and economy.

Marisol never shames or humiliates her subjects; she loves them too much, even when they appear ridiculous, such as Emily Roebling and her chicken in the 1989 sculpture "John, Washington & Emily Roebling Crossing the Brooklyn Bridge for the First Time." Marisol depicts their fierce pride as simultaneously heroic and comic.

A gift for blending moods, imagery, textures and mediums gives Marisol's art its disarming lift and leaves the viewer with a pleasurable afterglow. This exhibition is a party you don't want to leave.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.