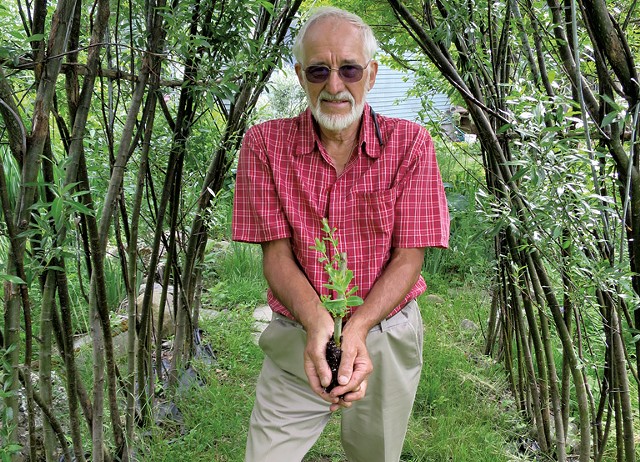

- Matthew Thorsen

- Michael Dodge

You might think of willows as the weeping kind, with their cascading branches that fall to the ground. Or you might picture a pussy willow, with its kitten-paw buds soft to the touch and pretty to display. For the average person — and even many seasoned gardeners — the willow savvy stops there.

Not for Michael Dodge. The owner of Vermont Willow Nursery in Fairfield has about 300 different types of willow trees and shrubs on his property. Over a decade, Dodge has planted all but a few longtime natives there himself.

A professional horticulturalist who studied at the famed Kew Gardens outside London, Dodge is perhaps the most knowledgeable willow man in New England. Growers and botanical gardeners nationwide know of him, and customers in nearly every state have bought his cuttings — starting at a minimum order of 10 for $25. This spring alone, the nursery filled nearly 500 orders.

"The culmination of all my horticultural training has ended up with willows," Dodge says. "I was able to focus on a plant that I've discovered very few people know anything about."

Semiretired at age 74, Dodge strolls through his nursery, ticking off both the common and scientific names of each willow and pointing out interesting features. Goat willow, usually found in Europe and Asia, has leaves that start out golden in color and tufts of flowers that resemble caterpillars. Salix candida, with sage-green leaves, is native to Vermont. Another willow with yellowish stems grew from cuttings Dodge took from a tree along Interstate 89. He has a big cricket bat willow — used to make, yes, cricket bats in England.

The diversity of the trees fascinates Dodge. "I could spend the rest of my life [collecting them], and I wouldn't do more than scratch the surface," he says.

Willows are in the Salix genus — part of the Salicaceae family of plants — which includes more than 450 native species and more than 1,000 cultivated varieties and hybrids. Some willows stand tall and lanky and sway in the breeze. Others squat close to the ground, their leaves a dusty gray-green. Red curly willow has twisted branches that turn red in summer. The leaves of the woolly willow — or Salix lanata, one of Dodge's rarest — look like little clusters of rosebuds. Schwerin's willow seems to sparkle as its leaves, with silver-white backsides, rustle in the wind.

Dodge loves to discover new willows and track down rarely seen ones. In 2014, he led a small expedition up Mount Adams in New Hampshire to see a native species that stands just an inch tall.

Yulia Kuzovkina, associate professor of ornamental horticulture and a willow expert at the University of Connecticut, joined that trip. She says Dodge, who had contacted her a few years earlier to discuss a willow issue, has an impressive level of experience and connections with willow growers across the country.

"Plus, he's extremely enthusiastic about willows," Kuzovkina adds. "His enthusiasm has given him so much information."

Dodge grew up in the Lake District of England and started helping his mother in the garden at an early age. In 1964, after training at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, he boarded the Queen Mary I and sailed to the United States to take a job at the New York Botanical Garden. Later, he spent 26 years at White Flower Farm in Litchfield, Conn., working as a horticultural photographer and gardener.

Dodge and his wife, Sonia, a real estate agent, moved to Vermont in late 2005, after she was diagnosed with breast cancer, to live closer to her daughter, he says. (Sonia is now in remission.) They found a tasteful, blue-shingled 1850 house at the end of a dirt road, perched on nearly 50 acres of rolling hillside and fronted by large maple trees. He and Sonia loaded a U-Haul with shrubs and perennials they had planted in Connecticut and drove north.

The previous owners of their property kept lots of animals, which enriched the soil, Dodge notes. Vermont's notorious rockiness prevents digging more than three or four feet deep, but the constant flow of water down the slope and along the rock renders the soil moist and loamy, he says.

That and Dodge's green thumb have helped to turn his property into a plant lover's paradise. A bright-yellow swath of daffodils brightens the hill in springtime. In a low spot behind the house, he created a faux streambed with rocks and lined it with hosta, peony and iris. Asparagus and garlic sprout in a vegetable garden in early spring. Nearby are raspberry, blackberry and blueberry bushes. Among the willows stand a chestnut and elderberry tree, pear and plum trees, and dozens of apple trees.

Ironically, Dodge paid little attention to willows in his 40-plus years as a horticulturalist, though the trees are popular in England. In 2006, soon after moving to Vermont, he visited the Montréal Botanical Garden and saw a demonstration of living structures. It included a "fedge" — a cross between a fence and a hedge — made with willow branches, or rods.

Strong yet bendable, willow rods are used for structures all over the world, including the Weidendom (Willow Chapel) in Germany. That display got Dodge hooked on willows: "The usefulness of them," he says. "They're so flexible."

A few months later, while back in England to visit his mom, he stopped at several willow nurseries and met "the warmest people" who gravitate to willows. Having returned to Vermont, Dodge bought his first cuttings of about 10 cultivars at a flower show, then placed a large order with a Kentucky dealer.

"I had no idea what I was doing at that point," Dodge says. "I just wanted more willows."

The plants cooperated. Dodge says you can stick any willow rod in the ground, and it will grow.

As he collected more and more willows and photographed them, friends suggested he put up a website and start a business, which he did in 2012. "We made 100 sales in that first year," Dodge marvels.

- Matthew Thorsen

In the wide world of willows, this gardener soon discovered, many species and cultivars in nurseries and public gardens are inadvertently misnamed. Dodge immerses himself in research, studying the trees' characteristics and talking to experts everywhere. He has grown adept at finding and correcting willows with mistaken identities.

"The more I learned about them, the more challenging it was," he says.

Last year, he got embroiled in a big willow hullabaloo over the use of the wrong name for a group of popular Japanese pussy willows with red buds. Many nurseries were selling those willows under the label of a similar-looking but different species, Dodge explains.

This past April, Dodge helped Kuzovkina publish a paper with a Kew Gardens colleague in the journal HortScience, resolving the mystery of the misnamed pussy willow. Kuzovkina has a long list of other incorrect willow designations that she hopes to tackle with Dodge, she says.

"He has a good eye," she observes. "He is excellent in detection of the problem of species names."

Dodge has consulted with botanical gardens around the country to identify unnamed or improperly named willows. "There's a lot of fun to be had doing investigative work into these names," he says.

A less enjoyable willow challenge is his battle against a pinhead-size, shiny black beetle that has infested Dodge's crop. The natural pesticides he has tried seem to work on some plants but not others.

Dodge also has to fend off disease and hungry rabbits. And now that he has expanded his nursery to a second plot in a lower-lying area, he needs to find a way to divert the excess water.

Willow mania demands much of his time and attention, Dodge concedes.

"It's a real sickness, once it gets into you," he says with a smile. "But, you know, I've never been happier in my entire life."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.