Upon first glance, Macao Bravo's backyard man cave isn't a structure that immediately beckons for further investigation. From the street outside his Winooski home, the decades-old outbuilding, which once served as a garage and toolshed, looks like nothing more than a dry place for stacking firewood — that is, until one notices that its creatively arranged grid pattern of "firewood" in front is actually an ingenious privacy screen.

"Outside, you look at this place, it's ugly," said the Chilean-born Bravo in a thick Spanish accent. "But inside, people are surprised by what it can be."

Indeed, entering the 52-year-old's man cave is like taking a tour of Bravo's life: the places he's lived, the things he's done, and the rare and unusual artifacts he's gathered along the way. Its many small and eclectic touches reveal the personality of an interior designer, formally trained in Spain, who is always seeing new potential in old and discarded objects.

Inside, visitors pass through a narrow passageway where Bravo stores his tools and woodworking supplies. Along one wall, an electric guitar body in mid-repair sits in a vice. Does Bravo play? "I try," he said with a chuckle.

From there, we passed under a bicycle wheel mounted decoratively on the ceiling and entered the man cave's main chamber, where an old woodstove abuts one wall. Three refurbished chairs, all covered in furry white mountain-goat skins from Chile's Patagonia region, face a flat-screen television mounted on the opposite wall. On the day of my visit, the TV displayed BBC video footage shot high in the Andes Mountains.

The ceiling is lined with the flags of the various countries and regions where Bravo has lived or traveled: Chile, where he was born; Spain, where he spent most of his childhood, and where Bravo's 15-year-old son still lives; the European Union; Spain's autonomous Galicia community; and Vermont, the last of which Bravo has called home for eight years.

Hanging above the back wall is a curtain-covered loft spacious enough to sleep in, though it's currently used for storage space.

"I love it in here. It's so comfy!" Bravo said with obvious glee. "When it's cold out, I start a fire inside, watch TV, read books. It's good!"

Still, it's hard to envision Bravo sitting still for very long. The walls and ceiling of his man cave are decorated with objects that pay tribute to his active outdoor lifestyle and connection to nature: deer antlers, horseshoe crab shells, skis, mountaineering gear — snowshoes, climbing ropes, crampons, an ice ax — as well as a fishing pole that Bravo's father-in-law gave him for sea casting. There are even flashing colored disco lights, presumably for use in more gregarious times.

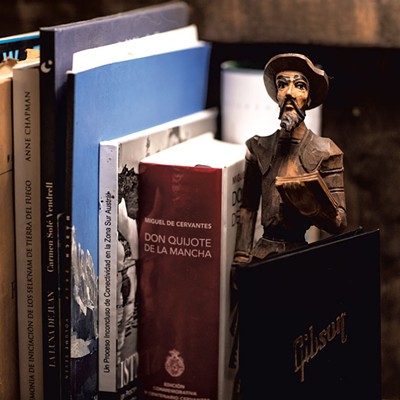

There are some signs of more placid indoor pursuits, including a card table and bookshelves for rainy days. On one shelf sits a row of Chilean pisco liquor bottles, whose black clay shapes resemble the massive stone carvings on Rapa Nui, aka Easter Island, off Chile's Pacific coast. Elsewhere in the room, Bravo displays hats once worn by his various family members.

"It's really Macao and who he is," said Bravo's wife, Amy Houghton, a landscape architect with Wagner Hodgson Landscape Architecture in Burlington. "I come in here and find new things all the time."

"This part here is my small museum," Bravo said, leading me to a wall of cubbies full of artifacts he's accumulated in his global treks. Though most are easily recognizable — fossils, skulls, a large condor feather — there was one unusually shaped object I couldn't pinpoint. It's about the size of an adult's fist and resembles a conch shell. Bravo explained that it's the inner ear bone of a whale.

But not all the décor in his man cave has such exotic origins, such as an irregularly shaped, polished wooden shelf with intricate grain patterns. Though it looks like a slab of hardwood harvested from a South American rain forest, Bravo explained that he took it from a white maple tree cut in his backyard.

Bravo's heavy use of wood, Houghton noted, reflects the cultural influences of his Spanish and Chilean heritage.

"For me, it's really interesting to see how he uses wood," she said. "I feel like anything he does, even if it has a functional use, it still has to be aesthetically pleasing, as well."

Bravo's passion for repurposing the space began about six years ago, when he recognized that the old bones of this shed were more substantial than he had initially assumed. After Houghton bought their Winooski home in 2012 — the couple married the following year — Bravo was cleaning out the old shed, thinking of tearing it down, when he realized its potential. Apart from some oil stains on the concrete floor, he recalled, it had sturdy maple construction and a lot of life left in it.

Soon, Bravo was bringing home old and broken lamps, tables and chairs, repairing them and finding them spots in his man cave. Once, while the interior of the historic Champlain Mill in Winooski was being renovated to create the Waterworks Food + Drink restaurant and bar, Bravo salvaged a pile of discarded wood chunks that had been cut from the mill's old beams. He then repurposed them to create a support post for a new interior wall in the man cave.

"Hopefully, no one thinks I'm crazy, having a lot of garbage inside!" Bravo said.

That seems highly unlikely. Despite its abundance of once-discarded objects, there's nothing junky about the interior design of this space. In fact, Bravo said he'd enjoy designing man caves for other people, too, if and when he finishes this one. His wife agreed.

"I think he needs to do other people's places," she said half-jokingly, "because he can't stop working on this one."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.