- File: Oliver Parini

- Sheep at Shelburne Vineyard

Twenty minutes south of Burlington, along Route 7, sits Shelburne Vineyard, a 4.5-acre farm, winery and tasting room just a short walk from the Shelburne Museum. Oenophiles can tour the winemaking operation, relax on an outdoor patio and sample about a dozen wines, many of them award-winning.

On the first Thursday of each month, Shelburne Vineyard (shelburnevineyard.com) hosts free concerts and local food vendors. On the third Tuesday of each month, it holds Wine & Story, a free storytelling event in the style of "The Moth Radio Hour."

And, for several weeks in spring and fall, visitors can meet the sheep that graze amid the vines.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- A concert at the vineyard

Ordinarily, the pairing of lamb with wine has a very different meaning to Ethan Joseph, Shelburne Vineyard's head winemaker and vineyard manager. But since November 2018, he has been working with a local shepherd and researchers from the nearby University of Vermont on a small, federally funded project to study the benefits of integrating sheep into the vineyard.

Their goal: to better understand what impact the practice will have on the grapes, wine, soil, sheep and environment, as well as on the vineyard's and shepherd's bottom lines. Researchers also want to learn whether other Vermont vineyards and food producers could benefit from similar practices.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- Inside the tasting room

On a recent sunny afternoon, a flock of five Suffolk sheep huddled along the eastern edge of the vineyard, too timid to approach a newly opened gap in their electric fence. Where the sheep presently stood, the vegetation was grazed clean to the ground. On the opposite side of the fence, however, the untouched grass stood taller than the sheep's withers.

With gentle prodding from shepherd Mike Kirk, of Greylaine Farm in Charlotte, the sheep overcame their skittishness and made a beeline into the tall grass. Inside their new pen, the ewes scurried about eagerly, gobbling white clover, dandelions and Kentucky bluegrass. Above the sheep's heads, the grapevines remained well beyond their reach.

"This basically looks like we mowed last week," observed Joseph, scanning the ground that the sheep had shorn clean in just four days. "We're already talking about how to scale this up and take it vineyard-wide next year."

This unusual collaboration began with an adorable photo of a lamb. In October 2018, Meredith Niles, an assistant professor in UVM's food systems program, was in New Zealand conducting research. On her first day there, she tweeted a photo of herself holding a new lamb on a farm in Marlborough, a renowned wine-growing region where grazing sheep amid vineyards is commonplace. Joseph and Kirk saw the photo, contacted Niles and, within weeks, the three had submitted a grant application to the U.S. Department of Agriculture to study the use of sheep in their own grape-growing operation.

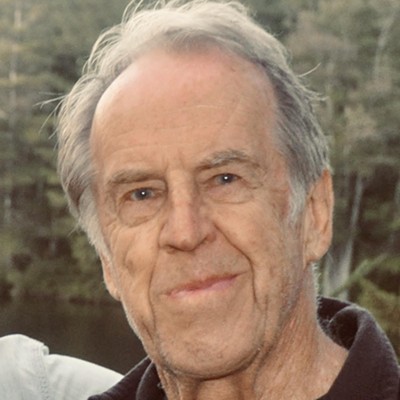

- File: Oliver Parini

- Ethan Joseph and Meredith Niles

Why do vineyards in New Zealand, the world's 15th-largest wine producer, routinely keep sheep around, when almost none in the U.S. do? The short answer, Niles explained, is because sheep are virtually everywhere in New Zealand, a country of 4.5 million people and 27 million sheep. By contrast, the U.S. has only 500,000 sheep.

"I had seen sheep in [New Zealand] vineyards for years but hadn't thought much about it," Niles explained. "And then I started to realize, no one else had thought much about it, either."

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- Wine tasting at the vineyard

As Niles discovered through her research, the relationship is symbiotic. The farmers grazing their sheep in the vineyards don't need to spend money on feed. The vineyards that allow grazing use fewer herbicides and mow less frequently, saving them money and labor. Though Joseph doesn't use herbicides or fertilizers other than occasional compost, he expects the sheep will improve soil health by aerating and fertilizing it.

Apart from Shelburne Vineyard, Niles knows of no other vineyard in Vermont that currently uses sheep; and aside from a few in New York's Finger Lakes region and some on the West Coast, virtually none are doing it elsewhere in the U.S., either.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- Outdoor patio at the vineyard

Kirk and Joseph see this project as mutually beneficial because it builds a relationship between two Vermont food producers and piques consumers' curiosity.

"Wine often gets overlooked as an agricultural product, mainly because people are used to larger-scale [production], like grocery store wine," said Joseph. He has about 25 acres under vine at four locations, producing 5,000 to 6,000 cases of wine annually. "This is a good example of how two different agricultural businesses can come together."

Kirk agrees. Greylaine Farm, which raises sheep and pigs for meat, gets very little public exposure. As he put it, "We're on a dead-end dirt road in Charlotte. No one sees our sheep unless they're flying over our land."

That's changing. This fall, sheep and visitors alike will be flocking to the vineyard.

What's nearby?

- Douglas Sweets

- Fiddlehead Brewing

- Folino's Pizza

- Shelburne Country Store

- Shelburne Farms

- Shelburne Museum

- Shelburne Orchards

- File: Oliver Parini

- Sheep at Shelburne Vineyard

À 20 minutes au sud de Burlington, sur la route 7, on découvre le vignoble Shelburne, domaine de près de 2 hectares, et sa salle de dégustation, à quelques pas du musée Shelburne. Les œnophiles peuvent visiter les installations, se détendre sur la terrasse et goûter à une douzaine de vins, dont plusieurs primés.

Le premier jeudi du mois, le vignoble (shelburnevineyard.com) organise gratuitement un concert et reçoit un restaurateur du coin. Le troisième mardi du mois a lieu la soirée Wine & Story, où chacun peut venir raconter une histoire au micro à la manière de « The Moth Radio Hour ».

Et pendant plusieurs semaines au printemps et à l'automne, les visiteurs sont invités à faire connaissance avec les moutons qui broutent parmi les vignes.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- A concert at the vineyard

Habituellement, l'accord vin et agneau revêt un tout autre sens pour Ethan Joseph, vigneron en chef de Shelburne et gestionnaire du vignoble. Mais depuis novembre 2018, il collabore avec un berger du coin et des chercheurs de l'Université du Vermont dans le cadre d'un petit projet financé par le gouvernement fédéral; ensemble, ils étudient les bienfaits que les moutons apportent au vignoble.

Leur objectif : mieux comprendre l'incidence de cette pratique sur le raisin, le vin, le sol, les moutons et l'environnement, ainsi que sur les résultats du vignoble et de la bergerie. Les chercheurs souhaitent également déterminer si d'autres vignobles et producteurs agricoles vermontois pourraient profiter de pratiques semblables.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- Inside the tasting room

Récemment, par un après-midi ensoleillé, cinq suffolks longeaient le côté est du vignoble, collés les uns aux autres, trop timides pour approcher la nouvelle zone de leur enclos. À l'endroit où ils se trouvaient, l'herbe avait été broutée parfaitement jusqu'au sol, tandis que de l'autre côté de la clôture électrique, l'herbe encore intacte s'élevait plus haut que leur garrot.

Il ne leur a fallu que quelques petites poussées du berger Mike Kirk, de Greylaine Farm à Charlotte, pour surmonter leur nervosité et se diriger tout droit dans les hautes herbes. Une fois à l'intérieur du nouvel enclos, les brebis se pressaient avec appétit, engloutissant trèfle blanc, pissenlit et pâturin des prés. Au-dessus de leurs têtes, les vignes restaient hors de portée.

« On dirait presque que l'herbe a été coupée la semaine dernière », remarque Ethan en observant la zone rasée par les moutons en seulement quatre jours. « Nous pensons déjà à pousser l'exercice plus loin et à laisser les moutons paître dans tout le vignoble l'an prochain. »

Et dire que cette collaboration inhabituelle a commencé par une adorable photo d'agneau en octobre 2018. Meredith Niles, professeure adjointe au programme des systèmes alimentaires de l'Université du Vermont, effectuait des recherches en Nouvelle-Zélande quand elle a publié sur Twitter une photo d'elle tenant un agneau dans une ferme de Marlborough, région viticole renommée où la présence des moutons dans les vignobles est monnaie courante. Ethan et Mike ont vu la photo, contacté Meredith et, en quelques semaines, le trio présentait une demande de subvention au département américain de l'Agriculture pour étudier l'usage des moutons dans leur propre production viticole.

- File: Oliver Parini

- Ethan Joseph and Meredith Niles

Pourquoi le 15e pays producteur de vin au monde laisse-t-il couramment les moutons paître dans ses vignobles, alors que la pratique n'existe pratiquement pas aux États-Unis? Parce que les moutons sont absolument partout en Nouvelle-Zélande; le pays compte 4,5 millions d'habitants et 27 millions de moutons. En comparaison, le cheptel ovin des États-Unis ne s'élève qu'à 500 000 bêtes.

« Je voyais des moutons dans les vignobles [néo-zélandais] depuis des années, mais je n'y avais jamais porté attention, explique Meredith. Puis, j'ai commencé à réaliser que personne d'autre n'y avait réfléchi non plus. »

Comme elle l'a découvert dans ses recherches, la relation est symbiotique. Les agriculteurs qui font paître leurs moutons dans les vignobles n'ont pas à dépenser d'argent pour les nourrir, tandis que les vignerons, eux, utilisent moins d'herbicides et passent moins souvent la tondeuse, ce qui leur permet d'économiser temps et argent. Même si Ethan n'utilise pas d'herbicides ni d'engrais à part du compost de temps à autre, il pense que les moutons amélioreront la santé du sol en l'aérant et en le fertilisant.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- Wine tasting at the vineyard

En dehors de Shelburne, Meredith ne connaît aucun autre vignoble au Vermont qui utilise actuellement des moutons. Hormis quelques-uns sur la côte Ouest et dans la région des Finger Lakes dans l'État de New York, pratiquement aucun autre vignoble aux États-Unis n'a adopté cette pratique.

Mike et Ethan croient que ce projet est avantageux pour toutes les parties, car il favorise la collaboration entre deux producteurs agricoles de la région et il pique la curiosité des consommateurs.

- Courtesy Of Shelburne Vineyard

- Outdoor patio at the vineyard

« Le vin est un produit agricole souvent négligé, car le public est habitué aux [productions] à grande échelle, comme le vin vendu en épicerie », affirme Ethan. Sa production comprend environ 10 hectares de vignes répartis en quatre endroits et donne de 5 000 à 6 000 caisses de vin par année. « Voilà un bel exemple qui montre comment deux entreprises agricoles différentes peuvent travailler ensemble. »

Mike acquiesce. Greylaine Farm élève des moutons et des porcs destinés à l'abattage et n'a que très peu de visibilité. « Nous sommes situés au bout d'un chemin de terre à Charlotte, dit-il. Personne ne voit nos moutons à moins de survoler nos terres. »

Mais les choses changent et cet automne, moutons et visiteurs afflueront au vignoble.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.