- James Buck

- Kalchē wines at the Burlington Farmers Market

Kalchē Wine Cooperative knows how to throw a party. The Fletcher-based natural winery's chilled reds, ciders, coferments and piquettes — appropriately called "space juice" — are vibrant, experimental, immensely drinkable and downright fun.

The cooperative's female and nonbinary owners, a majority of whom are Black, celebrated their first release with a bash at Switchback Brewing in December 2021. Founders Kathline Chery, Justine Belle Lambright and Grace Meyer have since hosted wine nights at T. Rugg's Tavern, a spring Festival of Dionysus at Hotel Vermont and, in late June, a packed fundraiser for Vermont Access to Reproductive Freedom at the Wallflower Collective.

Even Kalchē's tent at the weekly Burlington and Jericho farmers markets is a blast: It's full of disco balls.

"A party environment is very much where these wines belong," Lambright said. "They are festive, and I think everyone who buys our wines should throw a party to drink them."

As fun as they are, the wines can also be moody, as the winery's name suggests. Kalchē is an ancient Greek word meaning "to catch the purplefish," Chery said — a metaphor for searching and longing for something highly prized. "Sometimes it's celebratory. Sometimes it's really pensive," Chery said. "We contain multitudes."

The cooperatively owned winery has serious goals: to broaden the definition of wine while, in the words of the owners, centering diversity, sustainability and the decolonization of wine.

- Courtesy of Jacquelyn Potter

- From left: Justine Belle Lambright, Grace Meyer and Kathline Chery

As they head into their second harvest, Kalchē's founders are right on trend with the experimental energy of Vermont's growing natural wine scene. Chery, the team's winemaker and director of production, plays with hybrid grapes, apples, cranberries, foraged botanicals, hops, maple sap and even products that would otherwise be wasted, such as leftover brine from pickled beets.

"We have a lot of soapboxes," Lambright said. "We hold on really tightly to our morals and values and what we won't do with the wine. But what the wine actually does is just Kathline, the fruit and nature."

According to Vivid Coffee owner Ian Bailey, who poured the winery's space juice at a Vermont wine pop-up in June, "Kalchē doesn't miss."

The winery occupies what was originally an extension of the cellar at Bob Lesnikoski's Vermont Cranberry farm in Fletcher. The team has worked with "Cranberry Bob" to plant a vineyard on-site. He's also their de facto machinist and mad scientist, with a telepathic sense of when something's about to break, Meyer said.

Related Vermont Cranberry Marks 25 Years as State’s Only Commercial Cranberry Grower

Young itasca, frontenac blanc, frontenac gris, frontenac noir and crimson pearl vines grow on the hill across from the winery, just above a cranberry bog that's been on the property for 25 years. Kalchē's owners pay rent when Lesnikoski lets them, Lambright said, and help press cranberry juice at the end of the season. The grapes they've planted will start bearing fruit in three years and reach their best quality in five.

For now, they make wine from what they have access to — and can afford — in Vermont's limited grape market. At Huntington River Vineyard, where they have a crop-share arrangement, they kicked off the harvest season with osceola muscat grapes earlier this month. They work with other winemakers and community members, too, purchasing, foraging or bartering for ingredients that include fruits and botanicals not commonly found in the strict confines of the traditional wine world.

- James Buck

- Grace Meyer with Kalchē wines at the Burlington Farmers Market

"There's an abundance of flavor right around us," Chery said. "Being a nimble and scrappy business — that's definitely a plus."

Despite the wine industry's dominant narratives of "noble grapes" and "old world" appellations, that flexibility is nothing new.

"That perceived 'normal' took the place of what was already here," Chery said. "When we're talking about decolonizing wine, this is it."

Kalchē's experimentation has occasionally been confusing to the powers that be, especially when it comes to how they describe what's in the bottle. Meyer, the winery's director of internal business, has spent a lot of time on the phone with the federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), which regulates labeling.

"With this changing landscape, they've been incredibly kind and helpful," Meyer said. "But they're all telling me different things."

Viburnum, an early release in collaboration with subscription-based Viticole Wine, was particularly confounding. It was a piquette — created by an old-school method of rehydrating and repressing grape skins that many natural winemakers have returned to over the past few years. Into it went winery scraps, foraged high-bush cranberries and a touch of maple syrup for bottle conditioning.

After lots of back-and-forth — and testing at the TTB's formula lab — the federal agency required Kalchē to put language on the label that made Viburnum seem "like Franken-wine," Meyer said. "We had to call it 'a blend of sparkling other than standard grape-cranberry wine with grape wine.' Who wants to drink something other than standard? They haven't evolved to add inclusive language for winemakers like us."

Kalchē's business structure goes against the Big Wine narrative, too. The three founders have 30 combined years of hospitality and wine industry experience in Vermont, Texas, Oregon, New York City, Cape Cod and Boston. Starting the winery, Meyer and Lambright knew it would be a cooperative, even before Chery joined the team. They wanted to make sure everyone involved would have a voice and that the business would operate with equity and transparency, they said.

"Justine and I had worked enough places that we were pretty convinced the current model of modern business didn't work," Meyer said. "It definitely didn't work for us."

They were inspired by the energy and community support surrounding Burlington's Oak Street Cooperative, now the home of Poppy, Café Mamajuana and All Souls Tortilleria. Matt Cropp, executive director of the Vermont Employee Ownership Center, was central to creating that cooperative, so Lambright and Meyer went to him.

Related Café Mamajuana and Poppy Café & Market Bring New Energy to the Old North End

"[Cropp] helped us put the pieces together for the worker cooperative, explore what other options might look like and zero in on this," Meyer said.

Kalchē differs from most of the businesses Cropp's organization works with, he said. While the nonprofit does support some startups, it focuses on ownership succession for existing businesses.

Lambright and Meyer had previously worked together, "so in some ways, Kalchē was a hybrid of a startup and a conversion," Cropp said. "Their working relationship created a foundation of understanding and trust."

In broad-based employee ownership, all full-time employees have a path to becoming a co-owner of the business. Beyond that, there are two models. One is the Employee Stock Ownership Plan, favored by larger Vermont companies such as Gardener's Supply, Switchback Brewing and King Arthur Baking. Kalchē, by contrast, uses the worker cooperative model — a more direct form of ownership in which each member owns one share, and profit is distributed on the basis of labor contribution.

One of the biggest challenges for worker cooperatives is access to capital. "Inherently, the rate of return on capital investment in these kinds of generative, equitable forms of ownership is going to be lower than if you're a private equity firm trying to squeeze every last dollar out of the thing," Cropp said.

Other than the Vermont Employee Ownership Center, Kalchē's primary lender was the Cooperative Fund of the Northeast, a community development loan fund originally founded in 1975 by food co-ops to lend to one another.

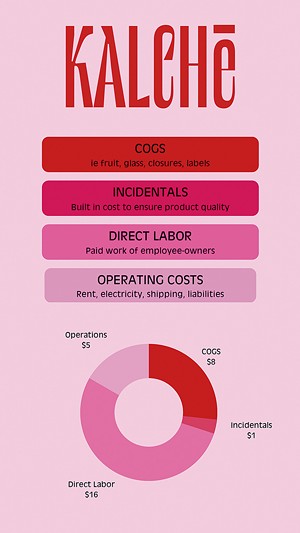

- Courtesy

- Kalchē's "Transparency Tuesday" Instagram graphic on the amount of money it costs to make a $30 bottle of wine

Kalchē's founders have been open about how they were able to raise funds to start the business. As part of a series of "Transparency Tuesday" posts on Instagram, they broke down the unpaid equity ($66,000), lender contribution ($100,000), friends-and-family loans ($35,000), unpaid salary ($60,000), and infrastructure support from Lesnikoski ($20,000) that got them off the ground.

"We're doing this the hard way. We're not independently wealthy, and we don't want to completely sell out and be told what to do by investors," Lambright said.

Down the road, the cooperative might have to deal with bigger decisions, such as what to do with profits or how to add another worker-owner, but those haven't come up yet. The founders are clear that their business isn't yet profitable. Compassionate lenders such as Vermont Employee Ownership Center and the Cooperative Fund of the Northeast "are willing to let us take the time to get where we need to be," Meyer said.

"Community businesses and solidarity economics work," Lambright added. "They just don't work as fast as toxic capitalism does."

To make money, Kalchē needs to increase production, lower the cost of goods, scale up and sell more wine. Right now, because it has to purchase grapes, Kalchē's wines don't come cheap. Lambright, the director of external business, said the owners have received a lot of pushback on prices at the farmers markets, where their direct-to-consumer bottles are often at least $30.

"We're selling a luxury product," Lambright said. "So, if people aren't necessarily in it for the ethos, it's hard."

Diaphanous, an apple-frontenac blanc blend that was also on tap at Hotel Vermont, cost only $25 at the market and sold out quickly. Kalchē's latest release is even more accessible: It's in cans.

"The Kalchē Kid," the label explains, honors the winery's "first can baby being birthed at the same time as the newest member of our team" — Meyer's son, Otis.

Chery made the easy-drinking, wine cooler-like Kalchē Kid by rehydrating pressed cranberries in a Seyval blanc-cider coferment. She and Lesnikoski did a run of 1,000 cans on a micro-canner that Lesnikoski rigged up, filling 10 per minute.

The $7 cans hit the farmers markets in early September. They're on the shelves now at Salt & Bubbles Wine Bar and Market in Essex and will soon be available at Burlington's Wilder Wines and Pizzeria Verità, as well as on draft at the new Onion City Chicken & Oyster in Winooski.

A fan of alternative wine packaging, Salt & Bubbles owner Kayla Silver has embraced Kalchē's new cans. "We love the Kalchē team, and this is a great way to taste their product in an accessible format at an approachable price," Silver said. The tangy, tart coferment is "perfect to pair with fall sweaters and campfire gatherings," she added. Sounds like a party.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.