- Sarah Priestap

- Sweet Doe Gelato, made with goat's milk

If gelato is the "why" at Chelsea's Sweet Doe Dairy, baby goats are the "who." Babies with clear eyes and long lashes that cock their heads to look at you, that lean into your chest when you pick them up, flooding your senses with animal affection. Their calls sound almost like a human infant's cry: soft and high-pitched.

At Sweet Doe, this season's kids live in open paddocks in the second story of the barn. On a muggy morning last week, hazy sunlight filtered in through gaps in the exterior walls. Broad posts and beams, in place for more than a century, formed a sturdy lattice overhead. Piled hay occupied much of the space, but in the doeling paddock, a dozen or so Nigerian Dwarf goat babies climbed on and over each other, bleating.

Some were as small as a beagle; others, twice that size. Their coats were solid black, bright white, chestnut red or fawn-colored; some were mottled or spotted, or had jagged, contrasting shapes. Reaching in to touch their eager faces was impossible to resist. In turn, they nibbled gently on my fingertips and nuzzled their heads in my palm.

"Come on out, Snowflake," said Mike Davis, opening the gate for a small, cream-colored baby. Mike runs the farm with his wife, Lisa, who is the operation's public face.

Snowflake was a quadruplet runt, tiny and limp at birth. "I thought he was dead," Lisa said, recalling the night he was born. "I held him upside down and shook him just to make sure he wasn't alive, and then he took one breath."

The Davises placed the sickly baby in a cardboard box and carried him everywhere with them for a week. He was scrawny and weak but able to suck down a bottle, Lisa said. As the days wore on, Snowflake gained strength; before long, he was prancing along behind Mike in the milking parlor.

The farm's bucklings, except a few kept for breeding stock, are typically wethered (castrated) and sold to local families as pets. But little Snowflake stayed on — the farmers just couldn't let him go.

"He has free range around here," Mike said, scratching the baby's back as it rubbed up against my legs. "He's the only one."

Lisa and Mike weren't born farmers. Like many agriculture entrepreneurs, they followed a winding path — fueled mostly by a love of food and cooking — to animal husbandry.

After college, Lisa lived in New York City for two decades. She worked in corporate communications and public relations for companies including the New York Times and Sony Corporation of America.

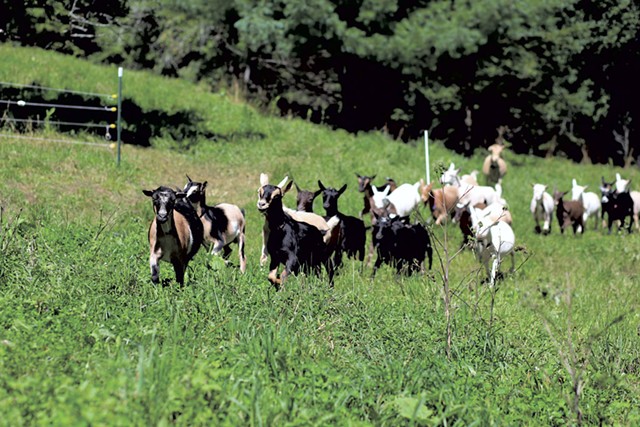

- Sarah Priestap

- Goats at Sweet Doe Dairy

Mike is a New Orleans native and Navy veteran. He always wanted to cook professionally but instead used the G.I. Bill to obtain a business degree from the City University of New York's Baruch College. Afterward, he managed international information-technology projects for New York Life Insurance.

"I used to travel to Asia," Mike said, smiling. "Now, I don't leave Chelsea." In fact, he added, "I don't even leave the farm. You have to [do that] if you're going to make a go of it."

Mike caught the farming bug at the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture (famed chef Dan Barber's place and the site of the original Blue Hill restaurant). There he volunteered on the livestock team for two years while living in New York's Westchester County.

"I loved all of it so much, I didn't want to leave," Mike said. At home, he worked on perfecting his gelato recipe, mostly for fun.

Slowly, passion gave way to aspiration: Why couldn't the Davises raise animals and make gelato professionally?

The couple moved to Vermont in early 2012 with dreams of producing sheep's-milk gelato. Though many of Chelsea's small farms have gone out of business in the past half century, the Davises cannot overstate the perk of living in an agricultural community.

"We've had the benefit of learning from farmers who have been doing this for four or five generations," Lisa said, standing in front of her 1790 house. The ancestral home of many members of the Hood dairy family, it overlooks narrow pastures and rolling hills to the south.

When the Davises moved in, the barn hadn't housed animals since the 1960s. "The barn was not suited for any kind of modern-day moving of livestock," Lisa recalled. Nor was the land particularly hospitable for sheep, which thrive on open pasture. Like most things in Chelsea, the farm is set into a steep hill with lots of wooded areas and brambly thicket. Sweet Doe's 81-acre spread is a far better habitat for goats.

Turns out, Nigerian Dwarf goat milk mirrors sheep milk in protein and fat content. So Mike could keep the recipe he'd been developing. What's more, the little goats — the smallest of all dairy breeds at 75 pounds when mature — consume less hay and make more milk than a 150-pound sheep.

But before the farm could start churning out gelato, its buildings needed work.

Neither Mike nor Lisa had experience in construction. Fortunately, their neighbor, Arthur Goodrich, did. "Arthur volunteered to teach Michael everything about construction," Lisa said. "He's here pretty much Monday through Friday, and he asks for nothing in return except friendship and company."

Arthur and Mike jacked up the barn where it was sagging. Using wood cut and milled on Arthur's property, they reinforced the floors and walls, reorganized the floor plans for goat paddocks and machinery, and built an addition for the milking parlor. Mike designed the parlor based on the system used at a sheep-dairying workshop he took in Spooner, Wis. They also built a new creamery structure with cold storage.

"We did the work ourselves as cost-effectively as we could," Lisa said.

As Mike and Arthur toiled on the farm, Lisa continued to work remotely in corporate communications. Even now, she's a full-time speechwriter for Dartmouth College president Philip Hanlon.

- Sarah Priestap

- Mike and Lisa Davis

"We would never have been able to do this without an off-farm job," Lisa said. "Any agricultural endeavor, especially dairy, is costly."

It might have been cheaper to torch the barn and start fresh. "We debated tearing it down," she said, "but I couldn't do it. Sometimes, you just have to do what's best for the property and what's in your heart, even if it's not cost-effective."

The build-out took four years.

In 2015, the Davises purchased 16 milking does and two bucks from Plainfield's Willow Moon Farm, where Sharon Peck — another mentor — produced silken fresh chèvre until 2016.

Since then, Mike has grown the Sweet Doe herd to 130 animals. Ninety of them are young does and breeding bucks, but the farm's 40 mama goats give about 15 gallons of milk daily during peak production.

All of it goes into the creamery, where Mike spends part of each day blending the milk by hand into rich, smooth frozen cream — it's thickened with eggs and tapioca and flavored with vanilla, chocolate or coffee. It tastes remarkably un-goaty.

Every week Mike adjusts the recipe to accommodate fluctuations in the milk's protein and fat contents. But the gelato's agreeable flavor also comes from the milk itself. Unlike many dairy goat breeds, Nigerian Dwarfs give milk that is mild and sweet.

As a business model, that's an advantage, Mike said: "Most average Americans are not used to goat flavor. We were raised on cows, and that's what our taste buds want."

Sweet Doe's first pints hit the market in May; New Hampshire-based Associated Buyers handles distribution. Many weeks, a truck picks up 60 cases; the gelato is in more than 30 stores from Kennebunkport, Maine, to southeastern New York. Vermont stores include Healthy Living Market & Café, Hunger Mountain Co-op, White River Junction's Co-op Food Store, and Essex Junction's Sweet Clover Market.

Lisa said the farm adds new accounts each week, even though anything labeled "goat" can be a tough sell for first-time buyers. "It's an entirely new product," she said. Indeed, Sweet Doe is one of just a few companies nationwide producing frozen goat's-milk treats.

- Sarah Priestap

- Goats at Sweet Doe Dairy

Goat desserts are a boon for the lactose intolerant, many of whom can digest goat's milk with no trouble. Most nut- or soy-based ice cream alternatives typically lack the creamy smoothness of animal-fat dairy. But goat gelato "really brings you back to when you used to eat ice cream," Mike said.

On Friday afternoons, Lisa can be found at the Chelsea Farmers Market, scooping gelato into cups and chatting effusively with visitors. I met her there for the first time, with a baby strapped to my chest. Lisa passed me a cup with one scoop of coffee and one scoop of vanilla. I was taken by the first bite. As it melted on my tongue, I felt my mood improve. I fed some to the baby, who slurped it down and leaned forward for more.

Back at the farm a month later, as Lisa and Mike discussed their rapid sales and distribution growth, I had to ask: "Why do the Chelsea market?" Surely the money earned couldn't justify the time and expense of being there.

"We wouldn't have this farm without our community," Lisa said.

"I wouldn't have even started," Mike added. "I didn't have the skills to do it."

My mind flashed to a chapter titled "Being Neighborly" in Joel Salatin's seminal how-to treatise on upstart ag, You Can Farm: The Entrepreneur's Guide to Start & Succeed in a Farming Enterprise (Polyface, 1998).

"Rural communities have a rich tradition of neighborliness," Salatin wrote. "If you think you are going to move out to a farmstead and do it all yourself in the old independent American spirit, you will fail."

During kidding season, Lisa said, neighbors show up just to help bottle-feed the new babies. They bring Crock-Pots filled with meals, knowing that the farmers have no time to cook.

Schlepping frozen treats to the market on hot summer afternoons is a small gesture, Lisa said, if it brings joy to her friends and neighbors. "It's a way to give back to this place," she said, "that has given me so much."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.