Online and mobile GPS mapping programs have improved considerably in recent years but are still a far cry from the gold standard of cartography. Ask Google Maps for driving directions from any U.S. city to Vermont without entering a specific address, and it'll direct you to a forest clearing in Morristown owned by Kristine and Brad Blaisdell. As Seven Days explained in a May 11, 2016, WTF column, Google's algorithms arbitrarily chose a spot where the couple stores firewood to represent "Vermont." Go figure.

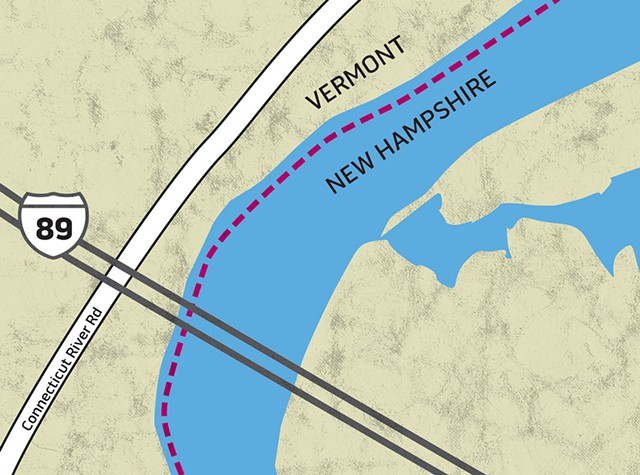

But occasionally, digital maps reveal deeper truths. Such was the case recently when a reader noticed that his smartphone app identified the Vermont-New Hampshire border as running not along the midpoint of the Connecticut River, where one might expect, but along the river's western edge.

Our reader also observed that the "Welcome to Vermont" sign on Interstate 89 north isn't posted in the middle of the bridge but on its western side. Is that because it's easier to erect highway signs on terra firma? Or does New Hampshire actually extend to Vermont's shore?

Turns out, the Green Mountain and Granite states bickered over this question for decades. This West Bank brouhaha, which is even older than the one between the Israelis and the Palestinians, wasn't resolved until a 1933 U.S. Supreme Court decision.

Short answer: The Vermont-New Hampshire border is the low-water mark on the western side of the Connecticut River. It's not the thread of the river, or centerline, which is the general rule when a body of water separates two states, as is the case with Lake Champlain between New York and Vermont.

Why not? For an explanation, we consulted Jere Daniell, 87, professor emeritus of history at Dartmouth College and a scholar of New England colonial history.

In 1664, King Charles II of England gave his brother, James, the Duke of York, the area currently known as New York and Vermont. As Daniell explained, that grant defined the province as running east "to the Connecticut River."

But Benning Wentworth, the British-appointed colonial governor of New Hampshire from 1741 to 1766, didn't toe that line. Between 1749 and 1764, Wentworth issued 135 land grants west of the Connecticut River in territory already claimed by New York. Wentworth's New Hampshire grants led to the chartering of 131 townships in what is now Vermont — including the first, which the self-aggrandizing gov named after himself: Bennington.

Then, in 1763, the British government decreed that Wentworth's grants were still part of New York.

"From 1763 until the American Revolution, there were conniption fits with the owners of the New Hampshire grants," Daniell said. A few residents purchased new titles from New York, others ignored the British decree, and "the more entertaining ones kept two sets of records, depending upon which authorities showed up at their door," he added. Armed conflicts between rival claimants eventually led to the formation of the Green Mountain Boys to stop the influx of New York settlers.

In 1789, New York and the Vermont Republic agreed to bury the hatchet. Vermont paid New York $30,000 to drop its land claims. Two years later, Vermont joined the Union as its 14th state, but the boundary dispute remained unresolved.

Fast-forward to the 20th century. In 1915, Vermont sued New Hampshire, claiming that it had been admitted to the Union as a "sovereign independent state" with its boundaries established by the revolution. Its eastern boundary, Vermont argued, was the thread of the Connecticut River. New Hampshire cried foul, and Vermont v. New Hampshire landed before the U.S. Supreme Court.

As Vermont Law School professor Jared Carter explained the 1933 decision, "the court split the difference." Vermont asked that its boundary extend to the center of the river; New Hampshire asked that its border run to where the vegetation stops on the west bank. But the justices chose neither, opting instead to put the boundary at the river's low-water line. As Carter put it, "Neither of them got what they wanted."

The case, Daniell noted, was rooted in property taxes and who could charge tolls on bridges across the river, but it also created other "entertaining consequences." For example, Daniell once took his grandchild on a tour of the Wilder Dam that spans the river between Lebanon, N.H., and Hartford, Vt., where, he learned, one of its six generators sits in Vermont.

Carter himself discovered on a river-float trip that the ruling also affects fishing rights. According to the Connecticut River Joint Commissions, resident Vermonters may use a Vermont fishing license anywhere on the river, and those holding nonresident Vermont licenses may fish the river from Vermont's shoreline. However, nonresidents who wish to fish from a boat "in these New Hampshire waters" must purchase a Granite State license.

Does that mean Vermont's Agency of Natural Resources has no jurisdiction over the Connecticut River? No, the agency does have jurisdiction, clarified Jeff Crocker, supervising river ecologist in the watershed management division of the agency's Department of Environmental Conservation. As Crocker explained via email, the federal Clean Water Act gives Vermont authority to regulate activities that affect its own waters, such as hydroelectric projects, water withdrawals, wastewater discharges and disturbances to wetlands.

"It's a fascinating story, steeped in revolution, kings, congressmen, dukes and governors," Carter added. "What Vermont and New Hampshire ended up fighting over, ultimately, was where the vegetation ends on a bank." And while it's "probably just a lot of sand and mud, there are real-world repercussions."

Isn't that always the case with border wars?

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.