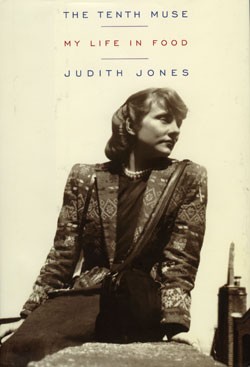

- The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food

If you’ve read recent confessional memoirs by culinary luminaries such as Ruth Reichl and Gael Greene, you may be surprised by the staidness of Judith Jones’ contribution to the genre, The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food. Reichl describes adulterous love affairs, while Greene delves into her trysts with celebs such as Elvis and Clint Eastwood. Jones, by contrast, seldom gets wilder than the occasional burst of sensuous food description. She stays serious and demure as she chronicles her youth and 50 years (and counting) as an editor at Knopf, during which she helped usher into print some of the most important cookbooks of the 20th century.

But maybe that reserve is appropriate. Jones, who splits her time between New York City and Stannard Mountain, Vermont, is a star maker, not a star. Though she collaborated with late husband Evan Jones on a trio of cookbooks and co-authored the L.L. Bean Game and Fish Cookbook with Angus Cameron, she’s generally been the woman behind the name on the bestseller’s cover.

It was Jones who lobbied to print a massive manuscript, co-authored by a Smith graduate with an unforgettable voice, after other publishing companies had discarded it. The book, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, made Julia Child famous. Jones also worked with Madhur Jaffrey, Claudia Roden and Marcella Hazan on their Indian, Middle Eastern and Italian magna opera, respectively — as well as many other authors. Modern American cuisine wouldn’t be what it is without Jones’ hand stirring the melting pot.

Reading about her formative years in New York, one learns that Jones’ adult passion for cuisine was a reaction against a genteel upbringing that frowned on fleshly pleasures, even those of nourishment. As a youngster, Jones (née Bailey) recalls, she sometimes wondered about the provenance of dishes served by Edie, the family’s cook. But, she writes, “Of course, I didn’t dare ask, because one wasn’t supposed to talk about food at the table (it was considered crude, like talking about sex).” Even making “appreciative sounds” during a meal could get one dismissed from polite company. The one cookbook the family owned was the restrictive Fanny Farmer’s Boston Cooking School Cookbook, with its emphasis on careful measurements and good nutrition.

Jones’ Vermont connection goes way back — her father was nicknamed “Monty” because he was born and raised in Montpelier. Spending her childhood summers in the family’s Northeast Kingdom cottage, she learned that people could buy vegetables from a “truck with farm-fresh produce” and meat from a traveling butcher. (In the city, groceries were purchased by telephone, and smelly foods such as onions and garlic were verboten.) As a Bennington College student during World War II, Jones got even more hands-on with her foodstuffs, cultivating a Victory Garden and doing “poultry duty,” which involved “beheading and plucking and eviscerating chickens by the dozens.”

But it wasn’t till she visited France, after graduation, that Jones realized just how much fun cooking and eating could be. “What seemed so rewarding,” she writes, was “finding in every village a small bistro where good food was prepared to order with care and with simple, good ingredients: a homemade pâté or maybe rillettes; a thick, meaty soup; a sautéed freshly caught trout; a flavorful, slightly chewy entrecôte; beautifully made French fries; and always good local cheese.”

Jones stayed in France, hoping to get “some exciting and interesting work,” and met Evan, her future life partner and collaborator, who was then in the midst of a divorce. The couple was determined to remain in France until they could return to the United States as husband and wife. That old-fashioned sense of propriety can still be felt in Jones’ restrained, none-too-juicy narrative of this emotional period in her life.

She gets more impassioned when she describes how she felt on returning home — deeply disappointed by the quality of American food. Jones writes, “So many ingredients I’d come to take for granted couldn’t be found in American supermarkets: no shallots, no leeks, no fresh herbs; no delicate, slim haricots verts . . . butter was overly salted, and there was no lovely crème fraîche; garlic . . . came in nasty little boxes so you couldn’t tell how dried up the cloves were.”

Then Jones snagged the job at Knopf, and, by her editorial choices and labor, began to change how Americans think about food. In Child, she found a kindred spirit. “[Child] realized . . . that a good book on French cooking for Americans had to be more than a collection of recipes,” Jones recalls. “Her role should be to translate classic cuisine for the American home cook.” Once Americans were bravely whipping up sole meunière and boeuf bourguignon, it became thinkable to nudge them in the even more exotic direction of Jaffrey’s curries and Roden’s Sephardic desserts.

Half a century later, we have an abundant crop of “celebrity chefs” and an entire television network devoted to the pleasures of the palate. The simple foods that Jones couldn’t buy anywhere, even in New York City, are widely available in supermarkets and gourmet shops. And Jones enjoys them, though she does so alone — 11 years after the death of her beloved husband, she still prepares the nightly dinner “ritual” the couple shared, complete with wine and candles.

As Jones’ narrative enters the present, we grasp the real influence of this circumspect woman who quietly but surely helped shape how we eat today. While the Childs and the Reichls of the world may be flamboyant, and their memoirs fun, there’s great value in Jones’ intimate, historical portrait of 20th-century cookery, one that’s free of chatty gossip and flip analysis.

At 83, now a senior editor and vice president at Knopf, Jones hasn’t slowed down — she thinks American culinary culture still has miles to go. “As I look at the carts at the supermarket laden with frozen dinners and other quickie foods that need only be heated in the sterile microwave,” she writes, “I often feel sorry for the people who are missing out on the endlessly rewarding experience of cooking.” While people used to cook unimaginatively on principle, now they do it for convenience. But not if this octagenarian flavor crusader has anything to say about it.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.