- Luke Awtry

- Memorial Auditorium

Burlington's mayor spent three years campaigning for his vision of Memorial Auditorium, battling political rivals, cajoling impatient residents and confronting the building's rising cost. For a time, it seemed his plans were doomed.

No, that mayor was not incumbent Miro Weinberger, who has grappled with Memorial Auditorium issues for much of his decade in office. The man in the hot seat was Republican Clarence Beecher, the city's leader from 1925 to 1929. In the end, mayor Beecher prevailed, convincing the city to construct the 2,600-seat brick auditorium on Main Street as a prestige event center and tribute to Burlington's World War I dead.

At the new auditorium's dedication, Beecher promised listeners that Memorial would "long be a blessing to Burlington," and for many decades he was right. The building he championed served as both a hometown hall and Vermont's equivalent of Madison Square Garden.

Aviator Amelia Earhart met 4,000 schoolchildren there in the 1930s; Duke Ellington, Nina Simone, and Simon & Garfunkel thrilled audiences in the '60s. Supertramp and Frank Zappa rocked the place in the '70s. But Memorial was also the place where generations of Rice High School students staged Stunt Night; where U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) played pickup basketball during his mayoral years; where the region's finest amateur boxers competed in Vermont Golden Gloves tourneys; and where, from the '80s into the new century, the city's teenagers gathered in the basement punk-rock club 242 Main to see everyone from local bands to Fugazi.

Today, many in Burlington view the auditorium not as a blessing but as a deadweight. "Look, there's no getting around it: The place looks terrible," Burlington author and historian Bill Mares said last month.

The building's appearance is no surprise: After decades of deferred maintenance, the auditorium was condemned in 2016 for structural reasons. The former showplace stands dark and useless, vexing another generation of city leaders. On Tuesday, Burlingtonians will vote on a $40 million bond issue, $10 million of which is earmarked for repairs and improvements to the auditorium.

- Courtesy of Louis L. Mcallister/UVM Special Collections

- Exterior historical view of Memorial Auditorium

In an email to Seven Days, Weinberger chief of staff Jordan Redell asserted that if the bond passes, "the administration will move quickly to stabilize the building with investments in structural and mechanical systems, and finalize a long-term plan for the building and the remaining bond proceeds (expected to be approximately $7 million)."

But the bond, like the auditorium itself, faces an uncertain fate. Reappraisal has raised property taxes for many homeowners, and it's unclear whether they will be willing to foot the bill to save the crumbling hall. It's also unclear what "saving" Memorial means.

In recent years, various proposals have called for reviving the building as an events center or including it in a "superblock" redevelopment project — or doing nothing, which may be what happens if voters reject the bond.

The bond requires a two-thirds vote to pass. If it doesn't pass, Redell wrote, "the period of underinvestment and uncertainty about the future of the building will continue and there may be further deterioration of the building that increases the challenge of future renovation efforts." She added, "No decisions have been made about how the City will proceed without the bond's passage."

However murky the auditorium's future is, its long history is rich and colorful. And its importance to generations of Burlingtonians is undeniable.

"If Burlington is going to remain the cultural center of the area, places like Memorial Auditorium have to exist," said Burlington's Alan Abair, who spent decades booking and promoting concerts at Memorial. "To see a place with such history become what it is now, you just have to wonder how it got so bad."

The Gilded Age

- Courtesy of Louis L. Mcallister/UVM Special Collections

- View of the balcony and main floor during a concert in the 1930s or '40s

Bill Mares walked up the steps of the auditorium's South Union Street entrance one day in November, intent on a show-and-tell about the building's origins.

Like many Burlingtonians, he has a long history with Memorial, remembering it as a place of high culture where orchestras played and famous actors performed, and as the wood-floored gym where he cheered on the Champlain College basketball team.

Unfortunately, he wasn't able to give a tour, as the Burlington Parks, Recreation & Waterfront department denied Seven Days' request to enter, citing the building's unsafe condition. So Mares just leaned closer to the window, squinting into the darkness of the lobby. Streaks of pale light crisscrossed the floors, revealing thick layers of dust.

"There," he said. His glasses were slightly fogged over from the steam of his own breath in the cold. "See them? Stacked by the wall right there. They're each brass and weigh almost 200 pounds. So you can imagine what a pain moving them is."

The plaques were just visible in the shadows. They list the names of 75 to 80 Vermonters who served in World War I. Names with stars beside them belong to those who died, Mares said.

"I just don't know what they'll do with them," Mares said, wondering about the plaques' fate should the auditorium be demolished. "You can't really auction off that stuff. Where would it go? Who puts a few tons of brass in their house?"

Those plaques recall a different era, as Mares and fellow historian Bill Lipke noted in their book Grafting Memory: Essays on War and Commemoration. The auditorium was one of many "living memorials" erected to veterans in the wake of World War I. "There was a widespread feeling that in addition to erecting a plethora of statues and stone piles, municipalities should honor the veterans with useful objects that would both honor the dead and serve the living by promoting interaction with the dead," they wrote.

While gratitude to veterans may have inspired support for building Memorial Auditorium, thereafter its local fame arose entirely from the events it drew — charity balls, celebrities and nationally known speakers. One of the first speakers, in May 1928, was Peter W. Collins, then a well-known anti-communist lecturer sponsored by the Knights of Columbus, who lectured on "Subversive Movements in America."

More happily, in July 1939, singer-saxophonist Rudy Vallee helped introduce an age of big-time music shows at Memorial. Vallee, a native of Island Pond and Vermont's first pop star, performed with his 30-piece orchestra — a homecoming show for his birthday. Two years later, Cab Calloway came to Memorial just three days before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The big band legend's arrival was so anticipated that local stores and restaurants advertised his itinerary, including where he would be dining.

- Courtesy of Louis L. Mcallister/UVM Special Collections

- A view of the stage from the 1930s or '40s

The Singing Cowboy got an even bigger reception when he rode into Memorial Auditorium in the early 1950s. The mayor declared it Gene Autry Day, and the city organized a parade before his performances. "The stores had Gene Autry sales for days ahead of the show. That's how much excitement there was for him to come," Bob Blanchard recalled from his home in St. Albans.

Blanchard, 70, grew up in Burlington's South End and is the founder of the Burlington Area History Facebook group. While any of the group's 17,000 members can share historical photos and recollections, Blanchard's painstaking research into the Queen City's past drives the thriving online community.

Some of Blanchard's own fondest Memorial moments include the locally famous basketball games between UVM and Saint Michael's College in the early '60s, when St. Mike's had a program to be feared.

"The fans would get there an hour before the game," he said, "UVM and St. Mike's kids just screaming and hollering." He said he can still hear St. Mike's fans roar when the band would play "When the Saints Go Marching In" as the team took the court.

"It was an incredible place to see a game," he said. "As a fan, you're right on the court."

Blanchard's memories of the auditorium as a music venue begin in the decade after Gene Autry, when folk and rock music replaced big bands and cowboys. In a recent post, Blanchard recalled Simon & Garfunkel's 1968 show at Memorial. The duo was booked as part of the Lane Series, the University of Vermont arts organization that started bringing top performers to the auditorium in the '50s.

While the folk act put on a show that locals with long memories still remember as legendary, it was most significant, Blanchard said, for being where the duo's version of "Bye Bye Love" was recorded for the hit 1970 record Bridge Over Troubled Water. The rapturous cheers and syncopated claps that give the live track so much energy are all Burlington.

Burlington Rock City

- Courtesy Of Mark Harland

- The Ramones, 1990

In the 1970s, concerts at Memorial took on an edgier vibe. Though the Lane Series still brought in world-class artists, and sporting events were still a draw, the arena became a rock and roll hub.

Nobody remembers that era better than Alan Abair. Abair grew up in Burlington. He perched on his father's shoulders when Roy Rogers rode Trigger into the auditorium, and he later performed in Rice High School's annual Stunt Night on the Memorial stage. But he became more than an occasional visitor in the late 1970s, when he was in his twenties.

Abair had set up as an independent promoter and began renting the auditorium for his shows. In 1983, he founded Union Street Management, and the city contracted with him to operate Memorial. Between 1971 and 1993, Abair brought a staggering array of stars to Memorial: Frank Zappa, Alice Cooper, Little Feat, Metallica, Pearl Jam, Bonnie Raitt, Jethro Tull, Melissa Etheridge ... The list goes on.

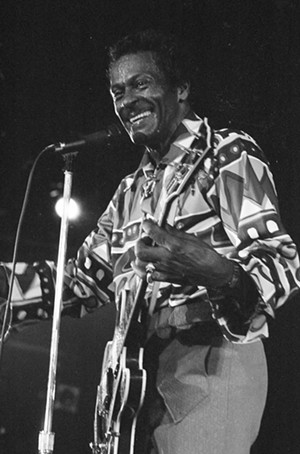

- Courtesy Of Mark Harland

- Chuck Berry, 1986

Abair retired from the concert business decades ago, but as he stood in the living room of his South End house recently, his passion for preserving Memorial's legacy was still evident. He had placed three cardboard displays on his couch, each bearing pictures from the decades of Memorial events. Alice Cooper, the Irish Rovers, Randy "Macho Man" Savage and Ray Charles all stared out from the board, beside news clippings of Geraldine Ferraro's visit in 1984 when she was the Democratic candidate for vice president. Spread out across his kitchen counter were countless ticket stubs, backstage passes and old show posters featuring the likes of a glowering Killer Kowalski, the wrestling star.

Renting Memorial was pretty informal back then. Abair would meet with city treasurer Ray Contois and fill him in on the performers he wanted to bring to town. And then Contois would simply give him the keys to the building.

Step by step, Abair also pulled the old hall into modern times.

Gone were the days when bookers would assemble a crew of their friends, or kids looking for tickets, to help unload trucks and gear. He made the venue a union hall, further ensuring the quality, safety and legality of the shows. He set up a box office liaison with the Flynn Theater, which made procuring tickets easier for the public.

Burlington singer-songwriter Peg Tassey saw many of the shows that Abair booked at Memorial. But she said one stood out.

"Metallica was hands down the loudest concert I have ever seen in my life," Tassey said of the thrash-metal kings' visit to the Queen City in 1989. She was one of the older people in the audience, she said, and one of very few women.

"It was an insanely hot night, and the floors were literally — and I am not exaggerating — flowing with three quarter inches of sweat," Tassey said, remembering a crowd of shirtless teenage dudes. She recalled bumping into Phish keyboardist Page McConnell and paying him back for a beer he'd bought her at a battle of the bands a few weeks earlier.

A Riot that Wasn't

- Courtesy Of Mark Harland

- Frank Zappa, 1988

That Abair was able to make Memorial such a temple of rock and roll is even more impressive given that mayor Gordon Paquette and the city council banned rock shows on all city-owned property after a particularly troublesome Styx concert at Memorial in 1977.

"Oh, jeez," Abair said, laughing and wincing as he recalled the incident, which he remembered as much milder than the "riot" some people called it.

Styx had sold out the auditorium two nights in a row. On the second night, a group of fans who didn't have tickets took out their frustration by pelting the windows and doors of the building with rocks, breaking glass all around.

The city overreacted, Abair insists, by banning rock concerts. He was forced to make do for a few years by booking a very different kind of entertainment — the German Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, for example.

That all changed when Bernie Sanders was elected mayor in 1981. Abair had known Sanders for a while; the two men played together on a recreation league basketball team that also included future Burlington mayor Bob Kiss. ("We weren't very good," Abair said, chuckling.)

Shortly after Bernie took office, Abair approached the new city treasurer, Jonathan Leopold.

"Look, I'm thinking of booking a show with the Animals,'" Abair told him, braced for immediate rejection.

"He looked at me and said, 'The Animals? Great!' And well, you know, that was it for the dreaded rock ban," Abair recalled.

Rescinding the rock ban came just in time for Mike Luoma, a Massachusetts native who attended St. Mike's in the 1980s and became a fixture in Vermont radio, as the music director for WIZN, WNCS and currently the online-only station WBKM. He hasn't forgotten the first show he saw at Memorial, the Gregg Allman Band.

"I can still remember that there was nothing in front of the stage back in those days," he recalled. "You could get right up against the wood."

The night Luoma became WIZN music director, rocker Eddie Money played Memorial. Luoma laughed maniacally as he recalled Money's backstage habit of walking up to just about anyone, hand outstretched and exclaiming, "Hi! I'm Eddie Money!" over and over again.

Over the years, the auditorium had developed a reputation for its allegedly less-than-stellar sound quality. But Luoma cites one of his favorite Memorial nights, when Frank Zappa played in 1988. Zappa, an infamous perfectionist, dispatched his crew the morning of the show to check on the acoustics. They used pink-noise speakers to flatten the sound in the cavernous, gym-like space and bring out low-end frequencies that would otherwise get swallowed.

"And I have to say, it was the absolute best I've ever heard that place sound," Luoma beamed. "It was pristine."

"I've always thought Memorial got a bad rap on its sound," Abair agreed about the venue's maligned acoustics. "Was it easy? Of course not; it was a big gym with hardwood floors. But if you put the time in, like Zappa did, it could sound great."

The Kids Are All Right

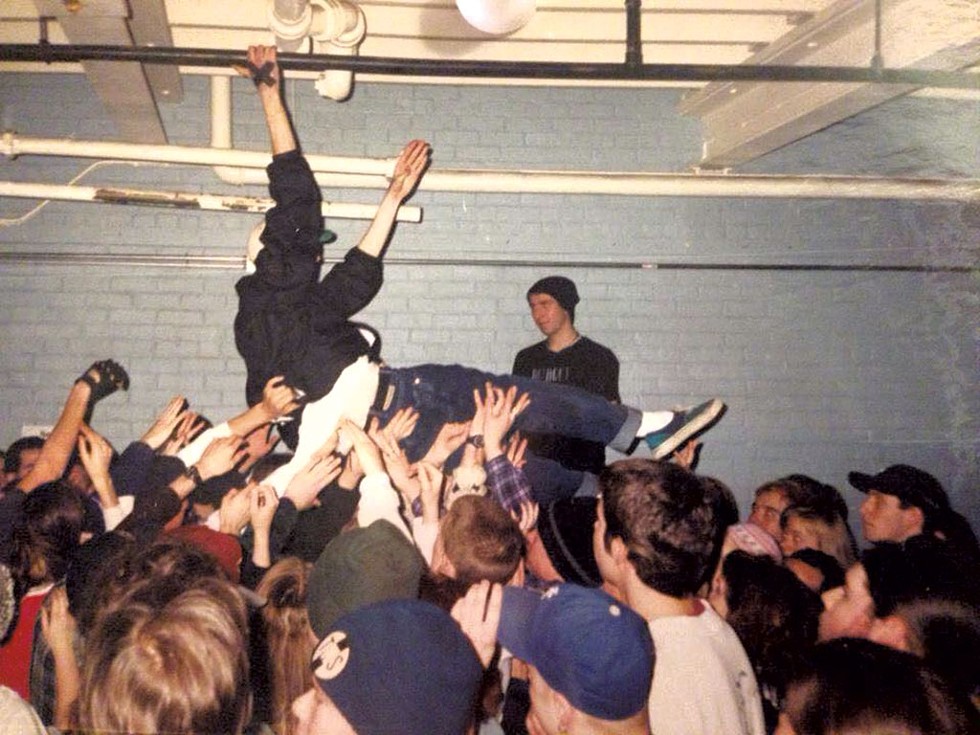

- Courtesy Of Joe Harig

- Crowd-surfing at 242 Main, 1995

While the big-name acts like Jethro Tull rocked upstairs in the 1980s, in the basement of the old hall, the Mayor's Youth Office established a space that would serve as an incubator for generations of Burlington musicians and fans: 242 Main.

The all-ages hangout opened on March 29, 1986. As much a drop-in center for the city's teens as it was a venue, 242 Main was for many years the only place in town that offered the sounds of the underground: punk rock, metal, hardcore and other, less corporate forms of heavier music.

For the next 30 years, 242 Main was the only place of its kind in Vermont. What started out as a place for Burlington teens to hang out — in a vacated water department office, no less — became so much more. Beloved local bands like Screaming Broccoli, Slush, Hollywood Indians and Dysfunkshun all made 242 Main their home, staging high-energy shows for crowds of kids who would go on to form the next generation of the city's musicians.

Sometimes the club would bring in bigger touring acts and punk legends, such as Agnostic Front and Black Flag. The late punk rocker GG Allin was once kicked out of 242 Main — which had a strict no-alcohol policy — after he threw a bottle of whiskey at local punk band the Wards.

But the club was always an odd fit as a city-run entity. As mayors came and went, the club's funding often did, as well — it even closed for a short period under mayor Peter Clavelle. Nonetheless, it was a vital part of the city's underground music community for decades.

- File: Luke Awtry

- The Wards performing at the last 242 Main show, 2016

For Big Heavy World, a nonprofit organization dedicated to documenting and preserving Vermont music, 242 Main was almost like a second headquarters. Executive director and founder James Lockridge still hopes to reestablish the club, which was shut down with the auditorium in 2016.

When it closed, 242 Main had the distinction of being the longest-running all-ages punk club in the country. "242 gave Burlington a claim to national history," Lockridge said.

He has been among the city's most vocal champions of investing in Memorial , because saving the arena could mean reopening 242 Main. He argues that the public firmly supports restoring Memorial, citing a 2018 survey commissioned by the city's Community and Economic Development Office.

More than 2,500 residents responded, and 84 percent supported renovating the building and saw its "meaning to the community as a gathering place," Lockridge said. Not only can the city revitalize Memorial, it must, he said. "242 put Burlington's kids, their young musicians, in the national history books. That can't be neglected any longer."

Faded Glory

- Chris Farnsworth ©️ Seven Days

- Alan Abair with some of his memorabilia

Abair and Union Street Management's tenure as auditorium stewards ended in 1993 when the mayor at the time, Peter Brownell, turned the site over to Burlington City Arts; later the Parks, Recreation & Waterfront department also played a role. While 242 Main continued in the basement and the upstairs hosted an occasional concert, Abair estimated that more than half the bookings became rent-free city-sponsored events like First Night.

"I think everyone meant well," Abair said, "but I don't think either organization really understood what Memorial was and how to use it."

Abair recalled mayor Beecher's words when he dedicated the building in 1928: "If the people will insist that the Memorial Auditorium be kept always at its best, it will ever be a real tribute to those living and dead who served their country well. If our citizens will use the building as their own and make it serve the needs of community, the State and even the Nation, it will long be a blessing to Burlington."

"That sort of dedication to the hall, what mayor Beecher was saying ... all those years ago, it just slowly disappeared," Abair lamented.

By most accounts, Memorial has become an eyesore, a graffiti-covered hulk. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. But by 1992, a consultant hired by the city to assess the auditorium called it one of the most dangerous buildings he had ever been in. Decades of deferred maintenance — "neglect," as historian Blanchard termed it — led inspectors to condemn it in 2016.

The brick exterior, largely untouched since 1928, is in need of refurbishment. Many of the original exterior details, including canopied entrances and elaborate globe lampposts, have long since disappeared. The building's interior is in even worse shape. Steel beams have rusted through, and the original framework shows signs of degradation. The great steel pylons have similarly corroded. Much of the brickwork is cracked or damaged by moisture — a roof replacement in 2016 didn't solve that problem.

"Why did they build a flat roof in Vermont?" historian Mares wondered. "Brave, maybe? Probably stupid."

Adding to the bill, the auditorium needs a new heating and cooling system. The entire 56,000-square-foot structure is presently heated by two huge boilers installed more than 50 years ago.

End Game

- Courtesy of Bill Mares

- Cleanup crew restoring World War I plaques in 2015

Memorial enjoyed one last act before it closed. In 2005, author Alexander Wolff and his wife, Vanessa, founded the Vermont Frost Heaves, an American Basketball Association franchise that played its home games at the arena.

For Wolff, who spent 36 years writing for Sports Illustrated and has penned several books on basketball, the chance to run a franchise was a dream come true. Finding an ancient gym like Memorial made the deal even sweeter.

"When I used to cover college basketball, I just loved these old rattrap gyms," Wolff said by phone. "I saw an opportunity to re-create that atmosphere with Memorial. It had this Phantom of the Opera feel to playing there, with dark nooks and crannies and fans hanging off the balconies."

Despite the charm, it was clear to Wolff that the auditorium was in rough shape. The city was short on tenants as the premises became more grim, so it was happy to accommodate the Frost Heaves and installed new hoops and backboards.

The gym played a role in the team's success. The Frost Heaves won league championships in 2007 and 2008 and were dominant at home.

"Those first two seasons, I don't think we lost a game in that gym," Wolff said.

Memorial was designed for high school basketball dimensions, so the cramped court gave the Frost Heaves an unusual home-court advantage, much like it did Champlain College's teams decades earlier. The Frost Heaves knew where to press opponents to play to the gym's quirks. For instance, the balcony would often interfere with passes or deep corner jump shots.

"That Union Street side was just nuts," Wolff explained. "Your player would barrel in for a layup, go too far out the door and suddenly be in the lobby with the popcorn machine."

"I loved the atmosphere so much," he said. "And it had a great legacy of basketball, with the UVM and St. Mike's games and then Champlain later. It felt like we were part of a tradition for a little bit."

Yet Memorial was, as Wolff put it, "just serviceable enough to sell tickets."

The Frost Heaves played their last game in 2010, unable to survive the economic collapse in 2008. When Memorial closed six years later, Wolff wasn't shocked.

"You can be as attached to a place as possible, but if it isn't safe, that's all there is to it," he said. "And if there isn't a sustainable way to bring the building into the 21st century, it's sad, but yeah, you have to move on."

That's what worries Blanchard, the local history buff. "It might be doomed, to be honest. It might be just too far gone," he said. "I just don't see how we can come up with enough money to fix all the things neglected at Memorial."

While some studies have suggested that $20 million is needed to restore Memorial, Weinberger has said $15 million is a more accurate number. But as has been the case in recent decades, Memorial has slipped down the city's list of priorities. It may again take a backseat to other pressing projects, according to Redell, Weinberger's chief of staff.

"The Mayor does not intend to commit the balance of the funds until a plan for the new high school is approved and funded out of recognition that the City and School District share their cumulative bonding capacity," she wrote, "and the new high school is a critical priority."

The mayor and city council have said there is a range of options for spending the $10 million, "from full renovation to removal." In other words, the money could be used to raise Memorial — or raze Memorial. It's the latter scenario that worries Lockridge.

"I'm disappointed that the mayor presides over a city government that allowed the negligent structural decline of the building yet is not committing to fixing what the city broke," Lockridge said.

However, Weinberger certainly sounded committed to Memorial in an interview with Seven Days' Courtney Lamdin in November.

"I walk by Memorial Auditorium every day," he said. "I refuse to be the mayor that allows this building, after decades of neglect and deferred maintenance, to crumble and cease to be usable ever again for the people of Burlington."

If he's able to follow through, Weinberger's stance on Memorial may hearten Lockridge and others who see the building not as a crumbling relic but as a symbol of civic pride worth restoring to its former glory.

Said Lockridge, "To me, Memorial is the palace of the city's spirit."

Best in Shows: Notable Events at Memorial Auditorium

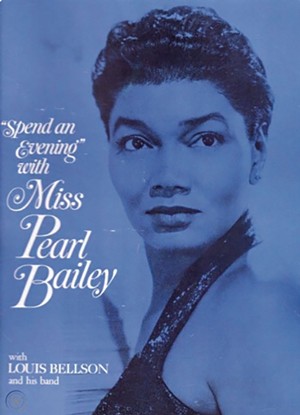

- Courtesy

- Pearl Bailey poster, 1966

Since it opened in 1929, Memorial Auditorium has hosted thousands of concerts, speakers and events. Here's a very abridged list of highlights, beginning with the venue's first concert.

- Burlington Symphony Orchestra, April 15, 1929

- Vermont Sportsmen Show, Hunting Dog Show, March 17, 1931

- Thomas E. Dewey, GOP presidential candidate, June 17, 1940

- Gene Autry, February 13, 1952

- The Beach Boys, August 12, 1963

- Pearl Bailey, March 4, 1966

- Simon & Garfunkel, March 12, 1968

- Duke Ellington, October 23, 1968

- Jesse Winchester, April 21, 1977

- Kraków Philharmonic Orchestra, featuring Yo-Yo Ma, January 20, 1985

- Philip Glass, November 13, 1985

- Vermont Golden Gloves Boxing, January 25, 1986

- Chuck Berry, April 3, 1986

- Alice Cooper and Motörhead, January 21, 1988

- Little Feat, October 17, 1988

- Fugazi, October 1, 1989 (242 Main)

- The Ramones, July 8, 1990

- Red Hot Chili Peppers with Pearl Jam and Smashing Pumpkins, November 2, 1991

- Bob Dylan, October 27, 1992

- WWF World Heavyweight Title Match: the Undertaker vs. Yokozuna, October 20, 1993

- Tori Amos, May 7, 1996

- Weird Al Yankovic, May 8, 2000

- Agnostic Front, October 30, 2001 (242 Main)

- Ween, October 31, 2003

- Deftones, November 23, 2003

- LCD Soundsystem, September 27, 2010

- Primus, October 13, 2013

- The Final 242 Show, December 3, 2016 (242 Main)

Correction, December 1, 2021: An earlier version of this story misstated the year in which Bernie Sanders was elected mayor of Burlington. He was elected in 1981.

Correction, December 2, 2021: This story has been corrected to reflect that Frank Zappa played Memorial Auditorium in 1988.

Correction, December 21, 2021: An earlier version of this story stated Rush played at Memorial Auditorium on April 17, 1975. That show was in fact in Burlington, Iowa, not Burlington, Vermont.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.