- Emily Rhain Andrews

Just north of the Milton-Colchester town line, sandwiched between an industrial stretch of Route 7 and a Gardener's Supply parking lot, sits an old white farmhouse that's seen better days. A large sign out front, bearing the sepia-toned visage of a 19th-century Union soldier, makes an earnest plea to passing motorists: "Help save my house!"

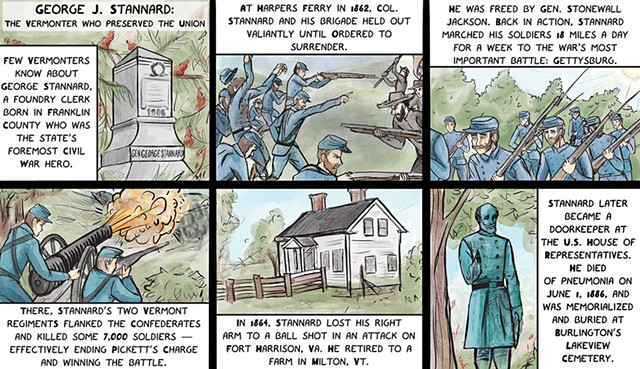

This weathered structure was once the home of Vermont's most important Civil War hero: George Jerrison Stannard (1820–1886). The Georgia, Vt. native may not be a household name, but few historians dispute Stannard's critical role in shaping the course of the Battle of Gettysburg and, hence, the outcome of the war.

As Montpelier historian and author Howard Coffin told an audience at the Pennsylvania battlefield on its 150th anniversary: "Vermont won the Battle of Gettysburg with Stannard's flank attack on Pickett's Charge." As Coffin later recalled, no one ever challenged that bold claim.

Yet despite Stannard's historical significance — he was also the first Vermonter to enlist in the Civil War — few memorials in the state bear his name. A granite monument marking his Franklin County birthplace is overgrown with sumac and barely visible to passing motorists. Similarly, an unremarkable plaque hangs in the Cedar Creek Room of the Statehouse, beside a wheelchair ramp leading to the cafeteria. You have to know where to find the statue of the one-armed general that marks his grave in Burlington's Lakeview Cemetery.

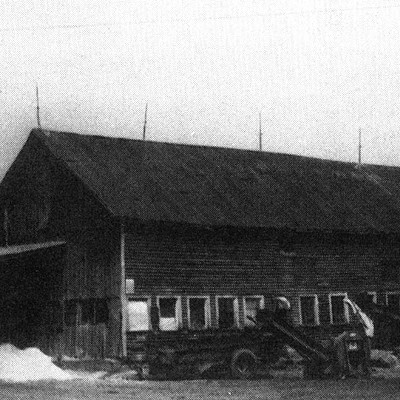

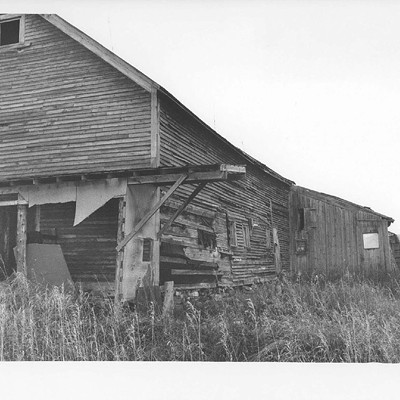

But now a group of dedicated history buffs from Milton is leading the charge to resurrect his house and legacy. The nonprofit General Stannard House Committee formed in 2014 to save and restore his postwar home, where he lived and farmed from 1866 to 1872. It's the last Stannard structure left; during a 1989 training exercise, the Milton Fire Department unceremoniously burned Stannard's barn, built specifically to accommodate his disability — he lost his right arm in combat in 1862.*

"How that came about, when the property was already on the state historic register, is a mystery. But it's a sad loss," noted committee cochair Bill Kaigle, one of four committee members who met this reporter for a tour of the house. "We're looking to honor Stannard with what's left."

The committee faces a daunting task — inside and out. Much of the home's exterior dates to its last occupant, Raymond Sanderson, who lived and farmed there from the mid-1900s until his death in 1988. Sanderson added the garage, which would be demolished if the house was saved. As Kaigle wryly noted about a TV antenna sticking from the roof, "Stannard got really good reception out here."

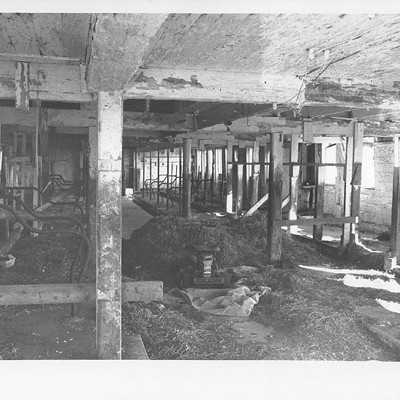

The interior isn't any better. To enter the original, 28-by-40-foot farmhouse requires stepping over a large hole in the floor. In what may have been the kitchen, a collapsed wooden beam bisects the room at a 45-degree angle. In another, a wooden door peels like a white birch. Plaster and rubble litter the floors. Non-original staircases are dangerously unstable.

On the tour, committee historian Terry Richards acknowledged that there's precious little inside the 1,600-square-foot farmhouse worth saving beyond its original wide-plank floorboards, hand-hewn wooden beams and fieldstone-and-brick cellar.

Over the years there have been calls to "burn it down, tear it down, put in a park, move it into town, move it out of town, let it collapse," Richards said. "It's all been on the table."

Why was such an important figure in Vermont history ignored for so long? Coffin, a Woodstock native, pointed out that he was never taught anything in school about Stannard or his role in the war. It wasn't until Ken Burns' nine-part PBS documentary series, "The Civil War," first aired in 1990 that Vermonters' interest in the war was rekindled.

Beginning in the 1990s and through the mid-2000s, several Vermont businesses and organizations spent time and money trying, unsuccessfully, to do something with the Stannard house. The Greater Burlington Industrial Corporation, which owned the property from 1989 until 2011, invested $15,000 to $20,000 to determine whether the house was salvageable and if so, what could be done with it. Ultimately, GBIC couldn't identify anyone with both the desire and funds to salvage the historical home, noted GBIC president Frank Cioffi.

In 2011, the Miller Realty Group bought the house and surrounding property and built an adjacent industrial park but agreed not to develop the historic site itself. Three years later, members of the Milton Historical Society formed the General Stannard House Committee.

Committee cochair Kaigle admitted that the projected budget for the restoration is daunting: The cost of stabilizing and renovating the structure alone is estimated at $220,000 to $300,000. Those figures don't reflect the costs of items community members have agreed to donate, such as a new roof. Taxpayers won't be involved, the Milton native emphasized.

Nevertheless, he and others on the committee believe the house still has intrinsic value beyond what few historic accoutrements are left inside. Kaigle envisions the house becoming part of a larger Civil War historic trail through the Green Mountain State. The committee will update the Milton Selectboard at its next meeting on August 15.

"Our main goal is to tell the story of Stannard and Vermont in the Civil War, in the house that he lived in," Kaigle said. "I think it would be a victory that Milton sorely needs. Milton needs a reason to come to Milton, a specific reason that other towns don't have. It would be a great heritage attraction."

*Correction, August 11, 2016: This article has been updated to clarify the circumstances under which the Milton Fire Department burned Stannard's barn.

![Lakeview Cemetery Tour [SIV509]](https://media2.sevendaysvt.com/sevendaysvt/imager/u/mobileteasertall/9497832/episode509.jpg)

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.