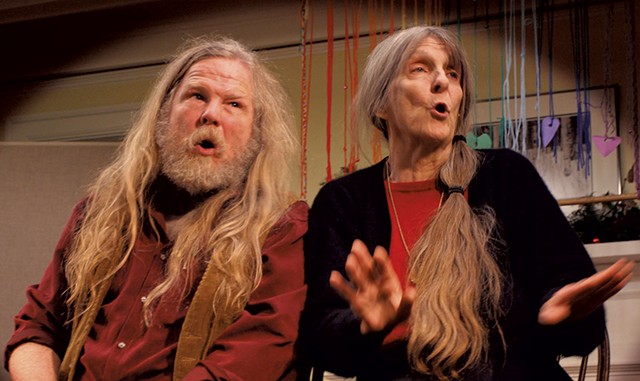

- Courtesy Of Terry J. Allen

- Tim Jennings and Leanne Ponder

Some couples are known to finish each other's sentences. Leanne Ponder (October 28, 1937-December 24, 2021) and Tim Jennings took that practice to another level. They learned to talk simultaneously while saying different words — and to make each of their voices distinctly heard and understood by the listener.

Intertwined or solo, Ponder and Jennings' voices expressed musicality in tone, rhythm and phrasing. Performing together as storytellers for about 30 years, the two presented original treatments of folktales to audiences in Vermont and beyond. Their stories were conveyed with humor and intrigue. The first one they learned to tell together — the quick and quirky tale of "Mr. and Mrs. Nyte" — was a bit grim, but audiences had to laugh upon its conclusion.

"It's a narrow field, two people telling the same story at the same time," Jennings, 73, said. "I believe that while we were doing that, we were the best in the world."

The married couple stopped performing a few years ago when Leanne became debilitated by Alzheimer's disease. She died of that illness on Christmas Eve at age 84, Jennings said, at their home in East Montpelier. In Leanne's last hours, he sang to her, talked to her and stroked her cheek.

"I told her it was OK to go, wherever she was going," Jennings said. "Into the light or into the dark."

Her death was "very, very peaceful," he said.

Leanne's own story resembles something of a folktale. She came from the Land of Enchantment — New Mexico — and found her home in the Green Mountains. She played ukulele as a kid and harp as an adult. She wore her hair long and made her place in the world writing poetry and making music, teaching children, befriending animals, and bringing stories to life.

"Leanne was ageless," said her longtime friend Wendy Everhart of Grand Isle.

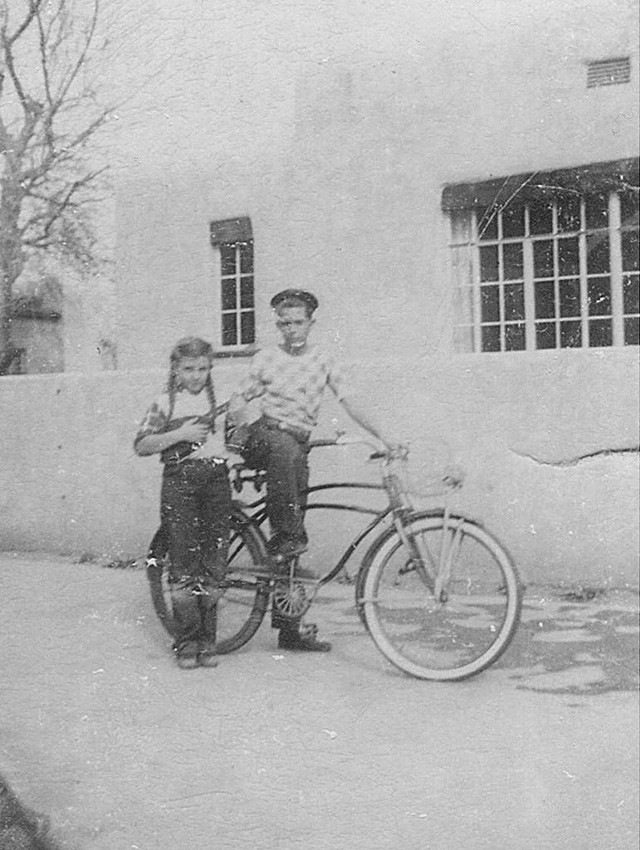

Leanne grew up in Albuquerque, a child of parents who did a little performing of their own before they had two kids. Leanne's mother, Zelpha, was a pianist who played organ and piano for silent movies; her father, Elmer, was a pitcher good enough to throw a few seasons for the Pirates and Cubs in the major leagues.

Leanne left New Mexico for college and then graduate school at Michigan State University, where she earned a master's degree in English. She was "knocking around for a while," Jennings said, before she made her way to Washington, D.C., and took a job traveling the country to teach writing to federal employees. She also wrote poetry and fiction, work that led her to Vermont for the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference in Ripton.

Leanne didn't like Vermont at first — it was too cold. But she warmed to the state and made it her home. From the early 1970s through the next 50 years, she patched together gigs as a writer and performer. She created a comic character called Bright Venus Smith, an 1850s backwoods peddler, and performed in libraries and historical societies around the state.

Leanne also taught in the Poetry in the Schools program, in which poets led weeklong workshops teaching kids to write in verse. She belonged to a cohort of poets who toured Vermont giving readings through a National Endowment for the Arts-funded program. Other participants included Hayden Carruth, Louise Glück, Galway Kinnell, Gary Snyder and Ellen Bryant Voigt, according to poet Geof Hewitt, who organized the program for the Vermont Arts Council.

- Courtesy Of Tim Jennings

- Leanne Ponder with her ukulele and her brother

"Leanne was a remarkably humor-filled and easygoing personality," Hewitt said. "She was not a high-strung kind of stereotypical poet, but a real person. And her poems are pretty powerful."

Inventive in her presentation of poetry, Leanne came up with an idea called Table Fables. It involved placing poems — her own and those of her students — in the plastic sleeves typically used for restaurant menus. She enlisted more than half a dozen Burlington restaurants to set these literary booklets on their tables, and she swapped out the poems twice a week.

Leanne's niece, Zina Pistor, recalled visiting her aunt in Burlington in the early 1970s when she was 10. She and her father traveled by motorcycle from their home in Oneonta, N.Y.

"I was in awe of her bohemian beauty, blue jean bikini, flowing long hair and overall cool Burlington lifestyle," Pistor wrote in an email. A decade later, visiting on her own, Pistor "shadowed" Leanne and her friends from "gallery to spoken word nights to late night living room salons."

By then it was the early '80s, and Leanne was living in her house on Pomeroy Street. She and Everhart, a dentist, met through mutual friends in the jazz scene and became close friends.

"We were like sisters joined at the hip back then," Everhart said.

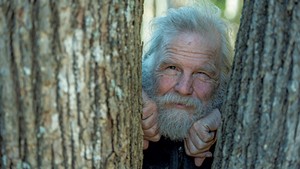

- Courtesy Of Zina Pistor

- Leanne Ponder

Leanne had virtually no furniture in her house, Everhart recalled, so the two would "sit on the floor playing Scrabble and smoking clove cigarettes all day."

When Everhart went away, she asked Leanne to care for her Lab, Watson. Though Leanne did have a bed in her home, she slept on the floor with the dog to keep him company.

"She was such a good soul," Everhart said.

Leanne met Jennings in the mid-'80s at a meeting of the Artists in Residence school program. He taught storytelling; she was teaching poetry. Then both living in Burlington, they decided to carpool to the next meeting, in Mendon.

The day was a full one. On the way home, Jennings performed a show in Brandon and then the two stopped for dinner in Middlebury.

"She came to my house after, and we spent the night talking and other things. And, basically, that was it," Jennings remembered.

"She was very genuine and deeply sweet," he added. "She had a warm and open personality, but she had some iron to her, for sure."

Jennings moved into Leanne's furniture-less house. But by the time the pair moved to East Montpelier, about 20 years ago, the house had become so packed with things that "you had to hold your body sideways to get around all the books and memorabilia they had collected," Everhart said. (The memorabilia included a baseball signed by Babe Ruth and Leanne's father, Elmer Ponder. Leanne gave the baseball to Pistor for her 50th birthday, along with other family souvenirs.)

During Leanne's years with Jennings, her creative focus shifted from poetry to storytelling. The couple practiced their craft for hours on end, spending months on a single story.

Jennings said he had confessed some guilt to Leanne for luring her from a "form of expression she had been very good at."

He recalled her answer: "You know, in order to write the kinds of poems I want to be writing, in order for them to be good, I have to wait until I'm in a weird headspace and then follow that further."

- Courtesy Of Tim Jennings

- Leanne Ponder

That wasn't necessarily good for her, Leanne told him, adding that what they did together was good for her. "And it was certainly very good for me," he said.

After more than two decades together, the couple wed at their home on January 1, 2011, at 1:11 p.m.

"There's something about getting up in front of God and everybody that's a very good thing to do," Jennings said of the marriage.

In 2015, Leanne published Tonight Not Even My Skin, consisting of poems she'd written decades earlier. When she discovered the poems in a box at her home, it was as if she had "found poems by somebody else [and thought], These are pretty good," she told Seven Days at the time.

As Leanne's health declined, performing became increasingly difficult. She and Jennings realized that rehearsing new stories was no longer useful. The two limited their repertoire, performing stories that were "embedded" within them. Leanne traded her harp for the ukulele.

"She didn't know the names of chords, didn't know the concept of chords, didn't know what the key was," Jennings said. "But I would start playing, and she would start playing along."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.