- Glenn Russell

- Kristian Brevik

Kristian Brevik says he started making art "as far back as I can remember." Recently, at his family's home in Port Townsend, Wash., he unearthed a drawing of a plesiosaur he'd made as a preschooler. No one knew at the time that the drawing — or his childhood obsession with prehistoric creatures — was a harbinger of things to come.

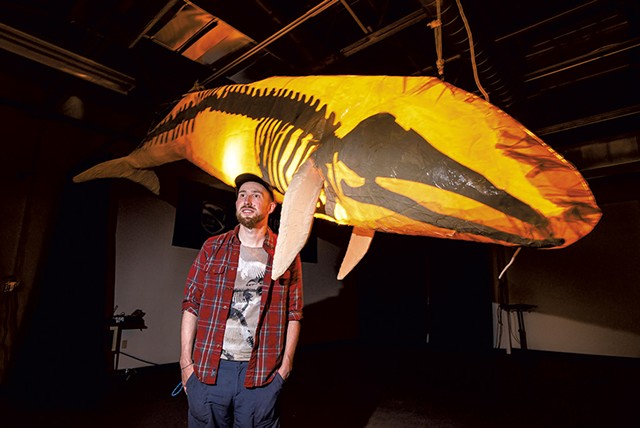

This weekend at Burlington's South End Art Hop, Brevik, 31, will display his latest creation: a 14-foot whale suspended from the ceiling of a gallery in the Generator maker space.

Brevik is quick to give other Generator members credit for helping to build the creature, and he notes the financial backing the nonprofit gave him to cover the materials.

"We challenged Kristian to make a big one," says Generator executive director Chris Thompson. "Generator has a fund to help projects come to life."

This whale's life began at the facility's laser cutter, where Brevik created a cardboard mold. He covered it with cotton muslin and resin, creating "modified papier-mâché," as he puts it. LED lights illuminate the whale from within, silhouetting its skeletal structure.

So, yes, the whale is also a whopper of a lamp.

Creating glowing critters is not new for Brevik. Last year's Art Hop introduced attendees to his smaller-scale whale lamps, roughly two to three feet in length. A pod of them seemed to swim above Hoppers' heads in front of the Lamp Shop on Pine Street. Their appeal was instant and has had staying power; Brevik continues to make the lamps and sell them in local shops, including Frog Hollow Vermont Craft Gallery and Thirty-odd, as well as on Etsy. Whether hanging or affixed to a base, each lamp is modeled after a whale of the orca, blue, gray, right, sperm or humpback variety.

A member of the local Illumination Collective — a group of artists who work with light and shadow — Brevik contributed his lamps to a "magical forest" at last year's Champlain Mini Maker Faire. He also created "glowing surprises" for an installation at the ECHO Leahy Center for Lake Champlain for the inaugural Highlight, a New Year's Eve celebration.

Though Brevik says he'd like his lamp making to become a viable business, his interest in whales is not trifling, nor are his intentions solely artistic. He is also a scientist and a champion of biodiversity.

In 2014, Brevik moved to Burlington to enter a graduate program in the Department of Plant and Soil Science at the University of Vermont. Generally, he's interested in the impact of humans on the planet's nonhumans. Specifically, as he explains on his website, his studies have a two-pronged goal: "to find a way we can understand how to make a world for our kin of all species"; and to explore the evolution of the Colorado potato beetle as a result of transposable elements and epigenetics.

Wait, potato beetle? That seems like a far cry from whales. Clearly Brevik's interest extends to creatures large and small. Regardless of size, he notes, all species can fall prey to their environments, whether they're sprayed with pesticides or they choke on plastic waste in the ocean. The tiny potato beetle has become resistant to more than 50 pesticides to date, Brevik notes. Accordingly, it gives scientists a chance to observe evolution practically in real time: the rapid adaptation of an insect trying to outpace constant chemical attacks.

"Our relationship with this beetle is that they're a pest," Brevik says. It's easy to see why — the bug can destroy thousands of acres of potatoes.

"How to cultivate empathy even for a species we dislike is a tough one," Brevik concedes. But heightening our empathy may be necessary for our own survival. In a paper posted on his website, Brevik argues that Earth's ecological crisis is directly related to humans' attitude of superiority to other species. We may consider unwelcome plants or animals "invasive," yet "Which species is causing the most damage on the Earth?" Brevik asks.

In a statement on his site, Brevik connects those ecological concerns with his artistic practice. "Coming to terms with the grief caused by the endangerment and extinctions of plants and animals which we humans are responsible for is a monumental challenge," he writes. "I work to find ways that art can help to foster a sense of deep connectedness with the nonhuman kin with whom we share the world."

Hence the whale lamps — not to mention the other creatures Brevik has constructed, which include wasps, centipedes, grasshoppers, trilobites and fireflies.

While science alone hasn't persuaded us to change our thinking about human-to-nonhuman connections, art can bring the issue "down to an individual scale," Brevik suggests. Last November he put that principle in practice when he presented a large installation called "Entangled: Ghost Whales" at a meeting of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium in the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Large "ghost whale" lanterns were suspended overhead and caught up in fishing lines. As photos of the installation show, the sight was gut wrenching.

Brevik's ambitions include finishing his PhD and "doing larger installations and partnering with organizations." One idea is to create an installation of lanterns equal in number to the surviving members of a particular endangered species — for example, 73 lanterns to represent the 73 southern resident killer whales thought to remain in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

Ecological crises happen in Vermont, too, Brevik notes, and his next project is locally relevant. Funded with a recent grant from the Vermont Arts Council, it will address the state's endangered bird species. Overall, Vermont lists 52 animals as endangered or threatened, as well as 163 plants.

Meantime, at this weekend's Art Hop, science and art will meet in a marine-themed installation at Generator. Creatures crafted by other Illumination Collective members will join Brevik's whale, Thompson says. Perhaps empathy will show up, too.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.