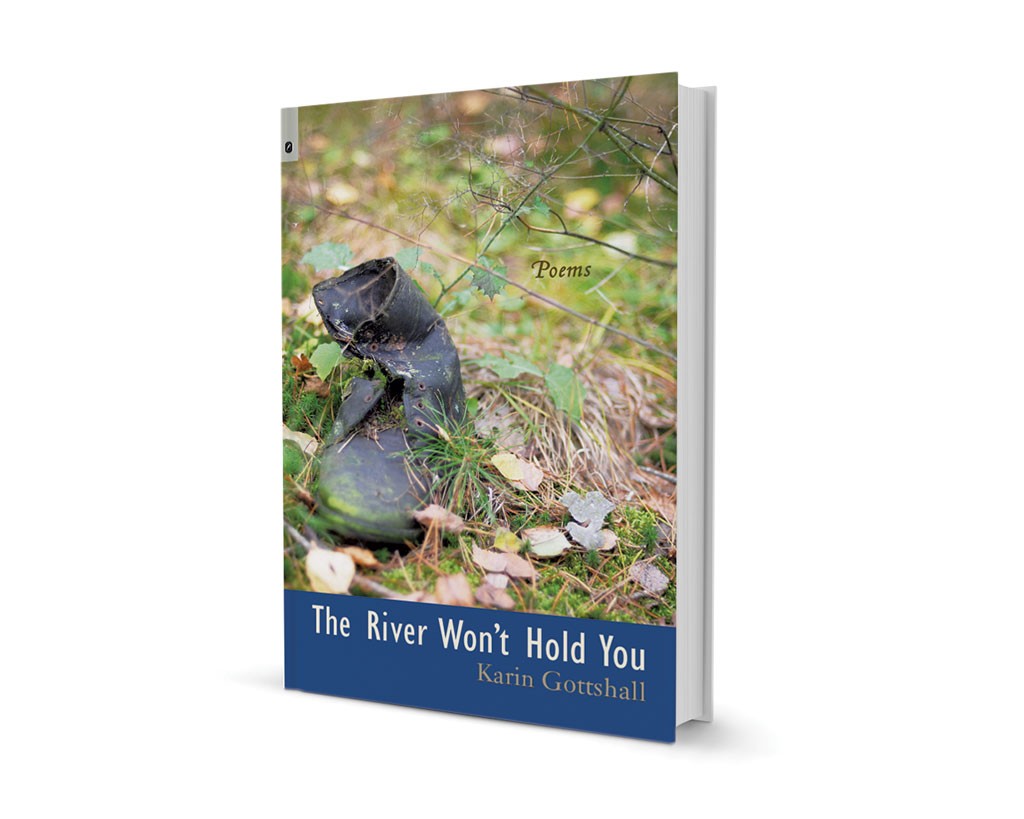

- The River Won't Hold You by Karin Gottshall, Ohio State University Press, 74 pages. $16.95.

Middlebury poet Karin Gottshall is the first to admit that her poems aren't heavy on cinematic action. "I lack for trains / and painters, whiskey and Sunday mornings. / Horseshoes. Hurricane lamps. Cast-iron pots, / revolvers, and gentle deft hands winding my scarf," she writes.

Winner of the Journal Wheeler Prize from Ohio State University Press, Gottshall tucks that disclaimer at the end of "Eros and the Reader," from her new collection The River Won't Hold You. There she also confesses she has "wanted / to live inside a novel more" than inside her own life. Yet, while readers may not find dust-ups, rowdiness, getaways or galloping horses in Gottshall's second full-length collection, they will find sewing notions, a doe's rib, snail shells, laundry lines, radiators, rivers, and the kind of loneliness that imbues these ordinary things with intensity and drama.

- Courtesy of Karin Gottshall

- Karin Gottshall

The River Won't Hold You is divided into three sections matching (approximately) the phases of a female's lifespan: girlhood, womanhood, elder years. Though Gottshall writes most of her poems in first person, this is not bald autobiography gussied up in verse. "When I tell you my childhood was wasted / at sea, you should bear in mind / I may be an unreliable narrator," she writes in "Earthquake." Then, just to shake readers up a bit more, she continues, "When I say I spent a year / in military school, disguised as a boy, / be skeptical — though in fact I did."

Instead of bearing witness to the facts of the author's personal history, the reader is privy to something perhaps much more interesting: her inner life. Reading Gottshall's verse, we feel like privileged eavesdroppers on someone in deep conversation with her imaginary friend.

"Was I a person who would / one day reach forty: a question I sometimes asked / the oven," Gottshall writes in "Parochial." In another poem, "Vespers," she reflects, "Would I ever have grand- // daughters: a question I sometimes asked the humidifier."

All these poems convey a prolonged loneliness. Yet this lack of human company — of sibling, best friend or loving lover — allows for the speaker's rich rapport with appliances, as in the excerpts above. She experiences a similar communion with the disc jockey's voice in "Rain" ("I turn on the / radio ... just to hear him breathe"), and, most significantly, with the page itself, where she writes the thing she needs into being. "Sometimes I say I'm going to meet my sister at the café —" Gottshall confides in "More Lies," "/ even though I have no sister..."

It seems that while she waits for the Godot-ish people of her life to show up, Gottshall's poems arrive, alive and precocious as the younger version of herself she describes in "The Tiger." "In the hundred // years I was nine I solved ten thousand math problems / but no one asked me what I loved, so I just // unbuckled my shoes each night, alone with it," she writes.

My favorites are those poems that shift from mournful to playful registers and back. In "Operative," Gottshall describes herself as a lone secret agent. She brags about her missions "[d]isguised as a shadow... // Disguised as a snow squall... // disguised as Aphrodite" until finally, "disguised as a boy, I went / among hunters, put the shot / buck's tongue back in his mouth, / kissed his eyes closed."

Another of this collection's joys is Gottshall's elastic sense of time. "It took me a hundred years / just to learn to thread a needle," she writes in "Mending." In "The Wasted Years," she invokes a blurry parade of months "filled with movies, / dreams about Venice, bread and raspberry jam. / A hundred books that drifted by / like laundry blown loose from the line."

The poems progress from evoking childhood spaces to articulating a young woman's obligations to depicting an old woman passing into an imagined afterlife ("My epitaph: her life was a series of stubbed toes / and tiger cats, the wind fooling around // under her skirt"). In the process, Gottshall offers readers not so much a novelist's narrative arc as the poetic equivalent of a quiver of arrows, whose flights are each of their fine lines.

And she demonstrates that writing where nothing definitively happens can be more intriguing than a narrative stuffed with busy action. Take "Yellow House Poem," which hauntingly commands readers to "[l]eave undug the backyard... / Leave unglassed the windows where rain / leaks in... there are no children here to soothe."

In advance of Gottshall's public reading of her contribution to Please Do Not Remove: A Collection Celebrating Vermont Literature and Libraries, a collection edited by Burlington writer Angela Palm, Seven Days asked her a few questions.

SEVEN DAYS: When you think of your body of work thus far, what is a theme, issue, technique or concern that persists?

KARIN GOTTSHALL: I can think of many, but maybe what comes to mind first is the largeness and limits of what we call self — the boundaries we have to learn to navigate from a young age, and what happens when those boundaries are violated by force or voluntarily given fluidity. I'm interested in what makes a self distinct, and in poems that run experiments in the transitional space between the self and everything — both material and spiritual — that surrounds it.

SD: Is your new collection a departure in any way?

KG: I hope I continue to grow in my craft and explore new subjects (or at least go more deeply into the old subjects), but otherwise I'm not sure there is much of a departure here. I seem to nurse the same preoccupations and obsessions that I always have. I do feel like midlife is very fertile territory, and many of the poems in this book address the questions and anxieties that arise when one has reached a point in life where there's a choice to be made between two possible futures. The book seems to me very much poised on that narrow line.

SD: Tell us about your contribution to Please Do Not Remove.

KG: [It] came about in a very different way for me than any poem I've ever written. I almost missed the deadline for submitting my piece to the project, because shortly after I'd agreed to write it, my mother was diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma. I wrote only one or two poems in 2014 because the year was so consumed with her illness and death. She passed away in July, and I am still trying to regain my sense of balance. "The Turnery" was written in the surgical ICU at Albany Medical Center. I'd pretty much given up on writing it and had let Angela know I probably wouldn't have time to write the poem, but somehow, in the midst of all of that sadness and anxiety, I turned to the assignment and ended up feeling so grateful for the focus and structure it gave me. It felt like getting a bit of myself back in the midst of an otherwise very traumatic and depleting experience.

The Sliver

I tease it out with tweezers — narrow dagger of glass, tipped with the thin rusty veneer of my blood. The wound bubbles: a small red mouth at my heel. Just when I start to feel like a rational human being something like this has to happen — a sharp insertion sending shivers all through me — but the body is a messy instrument with its groping senses and aversions. They say the girl locked in a chamber with only a thin splinter of an opening was entered and impregnated by a blade of light. Children whisper that glass in the bloodstream pierces the heart. For the first time, now, I notice it's spring: the needles soften on the evergreens and in the trees the crimson wedges of the cardinals call their song's sharp, clear incisions.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.