- Luke Awtry

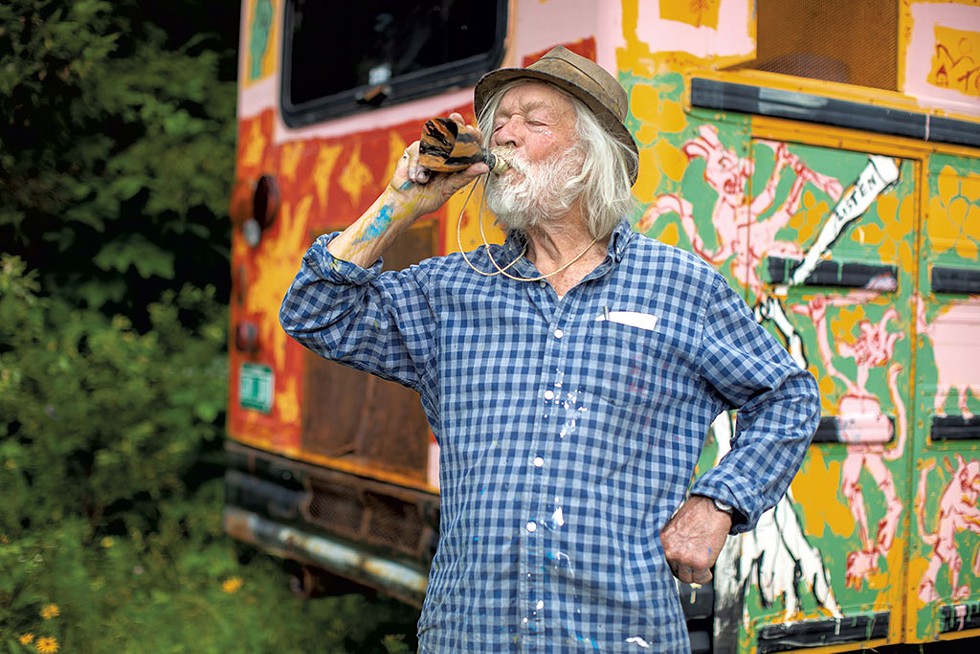

- Peter Schumann watching a pageant rehearsal

It was a warm afternoon in July, and I had come to watch the rehearsal in the backyard of the 19th-century farmhouse that serves as the nucleus of life at Bread and Puppet, a theater company that, for the past 60 years, has turned scraps of cardboard, used bedsheets and other debris into political performance art. "Who wants to be on deck? Maybe Cloud Orchestra?" one of the puppeteers suggested. Several people were carrying cardboard cumulus clouds to one side of the yard. Another small group was singing a dirgelike rendition of "Au Clair de la Lune." Schumann was not interested in hearing who was on deck. He wanted them to start. "Go, go, go, go!" he shouted in his thick, rough German accent. "Do it!"

Schumann, fresh from painting bedsheet murals in his studio, wore a paint-splattered button-down that had gone sheer with age, paint-splattered jeans and paint-splattered Birkenstocks. His toenails were thickly coated with dried paint. With his weathered fedora and beard, he looked like an aged Hummel figurine of a mad artist. I was sitting on the ground nearby, watching one of his chair legs sink into the mud.

A group of puppeteers led by Amelia Castillo assembled in front of him. "And now, a chapter in the life of Daniel Ellsberg!" Castillo announced. Another puppeteer, Tanja Höhne, took over the narration: "Pentagon Papers whistleblower who, in 1971, risked life in prison by copying and then leaking 7,000 pages of top-secret documents outlining the secret history of the U.S. war in Vietnam..."

The rest of the act proceeded in a similarly word-intensive fashion. At one point, two puppeteers lying on the ground mimed a Xerox machine with their arms and legs. More narration followed.

"And now, a whistle requiem for Daniel Ellsberg," Castillo said. She addressed Schumann: "And then we'll have whistles, and we'll do some sort of dance, or..."

Schumann had a few words of his own. "Oh, my God, you guys," he said. "It's incredibly overdone, and preachy, and all that. The Xerox is beautiful, but the other things are not OK."

"I agree, Peter," Castillo said, "and we'll cut it down, and—"

"It's just words, words, words, words. This is so, so tedious," Schumann continued. "Please."

Schumann's troupe performs its playfully acerbic anti-war, anti-capitalist shows around the world, but Glover is its geographic and spiritual home. Every summer, the theater stages its unclassifiable outdoor spectacles in a large, sloping meadow, which serves as a natural amphitheater. The Sunday afternoon circus is a variety show, part vaudeville, part agitprop; the pageant, which follows the circus, is a slow and ceremonial affair, a surreal moving tableau of giant puppets that feels more like a sacred rite than a work of modern theater.

On Saturdays, the troupe performs for a smaller crowd in a barn known as the Paper Mache Cathedral, which Schumann has covered from floor to ceiling with paintings and papier-mâché relief human figures. Thousands of people come to watch the performances every summer, a smorgasbord of humanity that includes aging hippies from near and far; weekending city folk drinking pét-nat out of Yeti tumblers; on at least one occasion, a shirtless man with a leather scabbard; college kids in search of a weird time; unimpressed 5-year-olds; and babies.

After the performances, the spectators wait in long lines for Schumann's bread, the same sourdough rye he learned to bake as a child in war-torn Germany. The shows involve a host of performers all dressed in white, like members of a utopian religious community, but Schumann alone is the visionary puppet master.

The existence of Bread and Puppet — a leftist quasi-commune in the middle of the Northeast Kingdom — has always seemed improbable. In July, I came to the farm for a few weeks to experience a small dose of this improbability, at a particularly fraught moment for the theater.

Schumann's wife and artistic collaborator of 60-plus years, Elka, died in August 2021, following a stroke. Schumann has had several strokes since May that have affected his speech, but not his insatiable drive to produce new work. He has offered no clear directive for what should become of the theater when he dies, nor can Bread and Puppet's unwieldy governing apparatus — the dozen or so members of the theater's board of directors, an informal group of advisers, and the amoebic society of performers that he and Elka have ushered into being — seem to agree on a vision for the future.

What is certain is that Bread and Puppet cannot continue as it presently exists without Schumann, because Schumann, for all of his emphasis on collectivism in his art, is the sun around which the theater revolves.

In the backyard of the farmhouse, the cardboard clouds took their places for Schumann. The puppeteers huddled together, shook the clouds to produce a thunder-like sound, then scattered with the arrival of someone bearing a large, tattered cardboard sun. Another puppeteer, holding a blank piece of cardboard, addressed Schumann: "There are children with this sign. And I don't have the exact words for it right now. It is a Frederick Douglass quote. But as long as there is inequality, there will always be a storm. Thank you." She took a small bow and walked away.

"Come back, come back, come back, come back!" Schumann bellowed. "Why not use a local weather report? They're always wrong. They're wonderful." The puppeteers regarded him uncertainly, as if he were an ancient talking tree. "This is all sentimental. It's missing intelligence, this act. Not enough to feed the mind. OK. Next."

Nobody seemed particularly eager to go next. "I think we just need more time, Peter," one of the puppeteers said.

"Time?" Schumann said. "I don't know what that is."

'Closest Thing to Magic'

- Luke Awtry

- Peter Schumann blowing a whistle

To spend any length of time at Bread and Puppet is to be dislodged from the continuum of normal human experience under 21st-century capitalism.

In the summer, the farm, which sits on close to 200 densely wooded acres near the top of a long, steep hill, becomes a teeming village of locals, performers from all over the world and perennial hangers-around who share in the upkeep of the Schumanns' artistic enterprise. Some people stay for the whole summer; others drop in for a couple of days or weeks. With the exception of a handful of staff members, who earn a very modest salary, Bread and Puppet relies on volunteers who work for free. Apprentices, who learn the ins and outs of puppetry, pay $1,200 for a three-week session. (In some cases, the theater offers financial aid for apprenticeships.)

Each day begins with a meeting at 9 a.m. to discuss the various tasks that must be accomplished. At any given moment, several people might be repairing broken puppets, pushing a stuck car out of the mud, smoking on the farmhouse porch, searching in vain for the right size drill bit, administering a stick-and-poke tattoo, or grinding grain for bread in a hand-powered mill. Some wretch — who, one afternoon in July, was me — must pick tiny shreds of gluey cardboard out of the grass after a papier-mâché session.

The plumbing is fragile in the farmhouse, where up to 17 puppeteers live during the summer, so most people use the outdoor privies, one of the few places at Bread and Puppet where you can be truly alone. Showers are only permitted once a week, which makes skinny-dipping in the nearby swimming holes both a practical and spiritual necessity.

Everyone gathers twice a day for a communal lunch and dinner. On Friday nights, Schumann makes potato pancakes for everyone on the outdoor grill. He uses a machete to flip them. "Why use a spatula?" he said one evening, drinking from a bottle of Shed Mountain Ale. "Much more efficient to use this."

A guy named Sandy Kepler, a retired teacher who lives in West Glover, periodically shows up to cook dinner for everyone. In the '90s, he told me, he helped devise the pyrotechnics for the pretend launching of then-U.S. representative Bernie Sanders from a cannon as a circus stunt. Kepler has never performed in a Bread and Puppet production, but he said he likes the general philosophy of the theater. I asked him what that philosophy was.

"I know what it is," he said, "but it isn't important to me to explain it."

There is no cell service here, or in most of the surrounding area, and the use of Wi-Fi is limited to a handful of staff members who are forbidden from sharing the password. In the absence of technological distractions, everyone becomes immersed in a relentless present. On one of my first days at the theater, I met Garrett MacLean, a photographer from Detroit who first came to Bread and Puppet in 2022 to make a documentary.

"Time moves so weirdly here," he said. "Every day feels like a week." After following the troupe on tour, MacLean said, he concluded that being behind the lens was keeping him from entering the slipstream, where the real experience seemed to be. He returned this summer, without his camera.

As a matter of principle, Bread and Puppet doesn't accept government, corporate or nonprofit funding. The theater sustains itself with private donations, volunteer labor, fees from the apprenticeship program, revenue from the brisk e-commerce sales of its handmade posters and prints, and a spirit of frugality bordering on masochism. The food processor in the kitchen only works if you press down on a piece of plastic in a very particular way; the blender is held together with duct tape that only sort of prevents liquid from seeping out. In the three and a half weeks I spent at Bread and Puppet, I encountered one pair of matching work gloves.

During the summer, 30 to 50 people might be living at the farm, in tents and broken-down school buses and other structures not usually meant for human habitation. Emma Doyle, who has run the kitchen at Bread and Puppet for the past three summers, told me that she once lived in the tiny cabin of a wooden boat that flooded whenever it rained. Her bedding consisted of a futon pad on the floor, and she got bruises on her hips when she slept on her sides. "I was going through a breakup, so I honestly didn't notice how rugged it was," she said.

In spite of these physical discomforts, or maybe because of them, the bonds at Bread and Puppet are deep. The theater recently held an art auction to benefit Linda Elbow, the Schumanns' first business manager and a mainstay of the company for decades. Elbow, who has dementia, lives in an assisted living facility in Morristown, and the puppeteers regularly visit her.

On July 25, a scrawny little Christmas tree was placed on one of the picnic tables, decorated with beer bottle caps and scraps of duct tape. For no particular reason, except that it happened to be five months until Christmas, the puppeteers had gone the night before to Schumann's house, a short distance from the farm up a gravel road, to sing carols and drink beer with him.

"This place is fucked up," said Mollie McGregor, a puppeteer from Toronto, "and it's also the closest thing to magic I have ever found."

Becoming Art

- Luke Awtry

- Puppeteers hoisting a giant papier-mâché hand

"To the north!"

Schumann was standing in the middle of the meadow, shouting directions at the puppeteers across a great distance. We were rehearsing for the Sunday pageant, which usually involves one or more massive puppets operated by dozens of people, who move them across the field at a slow, dreamlike pace. Schumann directs these spectacles to bring the sublimity of the landscape into relief. The hills in the distance, the sky and the clouds, he said, are more important to him than what the puppeteers are doing.

"The point is to introduce the audience to the cumuluses," Schumann told me. "Forget about the puppetry. These huge cumuluses, they are preaching."

When you're in the pageant field, maneuvering a swaying papier-mâché hand atop a 20-foot bamboo pole, the sermons of the cumuli are not always top of mind. During this particularly hot, humid afternoon, we were mainly concerned with figuring out where we should stand, a task complicated by the fact that Schumann's voice was a faraway yawp in the meadow.

There were four giant hand puppets in the field, each manned by four to six puppeteers. One group took a few tentative steps in a direction, which apparently was not north. "Nooooo!" Schumann bellowed. Then he seemed to have a change of heart. "Now, a few paces to the east!"

Before I arrived at Bread and Puppet, I'd worried, for legitimate reasons, that I was unsuited to the rigors of a performing arts environment. My theater résumé consists of undistinguished chorus roles in high school productions of The Music Man and Grease. I have no special facility with puppets and, frankly, find them terrifying. But as we schlepped the hands to and fro in the meadow, I grasped that the only qualification that matters at Bread and Puppet is a willingness to be nobody, a useful nobody. Only Schumann could see the totality of the painting we were somehow creating together, and only Schumann — maybe not even Schumann — knew, in that moment, what that painting was supposed to look like. I felt a strange sense of well-being. We weren't just making art. We were becoming art.

To participate in a Bread and Puppet production is to experience a kind of collective ego death. "You feel like you're being absorbed into a giant organism," said Clare Dolan, the creator of the Museum of Everyday Life in Glover and Schumann's assistant. Dolan has been part of Bread and Puppet since the early '90s. "This is probably what organized religion is trying to achieve," she said, "but I never connected with that feeling until I got here."

Puppet Purgatory

- Luke Awtry

- Gangster figures in the museum

Schumann's puppets are variously lumpy, leering, apoplectic, serene, beseeching, stoic, mirthful, sullen, up to no good. Almost every square inch of the cavernous 150-year-old dairy barn on the property has been consecrated to them. You would never want to spend the night alone in this barn, which serves as both a museum and a kind of puppet purgatory for the lame and unemployed.

Fifteen-foot-tall washerwomen with pendulous breasts loom over small, grimacing heads. There are legions of demonic creatures, masses of huddled figures no bigger than toadstools, perturbed-looking trees, impassive suns, pointing hands, ghostly horses, gangster figures in dark suits and Homburg hats whose expressionless white faces somehow radiate pure evil.

Collectively, they seem to possess a furtive, mycological consciousness. As you wander through the barn, you might get the uncanny feeling that the puppets are talking about you through a vast papier-mâché neural network. A profound melancholy hangs in the air, the ineffable sadness of huge animals in zoos and abandoned toys. I found that people at Bread and Puppet don't talk much about this feeling. It evaporates when you try to describe it.

The Impermanence of Everything

- Luke Awtry

- Peter Schumann and puppeteers in front of his bedsheet murals

Since his stroke in May, Schumann has been uncommonly productive, even by the standards of a man who has populated an entire barn with puppets and made, by his own estimate, some 200,000 paintings. Some are no bigger than postage stamps; others cover a whole school bus. For the past few months, Schumann has been completing an average of two murals a day on white bedsheets, which he gets for free from local motels. This summer, Schumann's bedsheet paintings adorned the walls of the 160-by-60 foot former veal barn near the pageant field, which Bread and Puppet purchased last year.

One morning, I visited him in his studio, where he had just put the final touches on a bedsheet painting of an ochre sun rising above eight writhing figures. He told me that he had started and finished in the exact length of time it took him to listen to Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 5, or about 22 minutes. What Schumann paints is often less interesting than how, and how much, he paints. He told me he works like "a wild boar," ravenously and without looking back. His creative constraints are wall space and the speed at which paint hardens. "Drying periods are my main problem," he said.

Schumann insists that he never knows exactly what he's going to paint until he gets started. He begins with a few thumbnail sketches, on which he spends "about half a minute," and then he tacks the bedsheet up on the wall and goes to work, laying down one brushstroke after another in the same way that most people breathe, automatically and without beating themselves up about how shitty that last breath was. When he gets bored, he stops.

"I'm very good at dilettantism, at never feeling like I even need to complete something," he told me. "Art education is something that results in gallery art and commercial art and professionalism, and professionalism obliges people to continue to do what they do. And then they are bored stiff with themselves."

Schumann believes in ephemerality as the organizing principle of the universe, in the impermanence of everything, including his own art. The barn, teeming with his papier-mâché life, was never meant to become a monument.

"It's here, but it might as well not be here," Schumann said. "A lightning storm strikes, or someone puts a match to it — that's it." Not to mention the less cinematic indignities to which papier-mâché is heir — rain, mold, insects, careless puppeteers, time. If the barn went up in flames, Schumann said, he'd get over it. "Make new stuff. What else is there to do in life?"

In many ways, an act of God would radically simplify things for Schumann and the world he and Elka brought into being. As it happens, lots of people want to preserve his art, and there is much disagreement among those people about how it should be kept alive when its creator is gone.

Dolan, who was on the Bread and Puppet board of directors until last November, told me: "There is near-universal agreement — actually, I don't know if I can even say 'near-universal' — that if you continue to make new shows with Peter's puppets, but he doesn't direct the shows, you can't call it Bread and Puppet. Can you use Peter's work to make new shows and call that something other than Bread and Puppet? Some say yes; some say no. Can you repeat shows that have already been developed and call that Bread and Puppet? Some say yes; some say no. Who should even be the arbiter of what is and isn't Bread and Puppet? There's no agreement about that, either."

Max Schumann, Peter's son, said these machinations are torture for his father. "He was the charismatic leader, and now he doesn't have the bandwidth or the patience to deal with all the administrative stuff," Max said. "And he hates it. It's bourgeois bureaucracy." Nor is he constitutionally capable of retirement. "He doesn't differentiate between work and life," Max said. "He doesn't recognize the legitimacy of those kinds of capitalist categorizations."

Max is on the theater's board of directors, along with two of Peter and Elka's other four children, Tamar and Solveig. Bread and Puppet has become such a sprawling entity, with so many people invested in its future, that none of the Schumann siblings could simply take the reins, Max explained. "I'm pretty sure everyone would agree that no one can replace Peter."

Peter doesn't seem particularly optimistic about the fate of his enterprise. "Maybe the best thing is to throw it all overboard," he said. "But that has problems also. People rely on this. If you start thinking that you want to hang yourself, you would still have the burden of thinking that through."

Origin Story

- Luke Awtry

- Papier-mâché puppets in the museum

In February 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev, the last president of the Soviet Union, invited a special delegation of American artists and intellectuals to the Kremlin in an effort to foster understanding between the Cold War rivals. Among the passengers on the first-class charter flight from New York City to Moscow were the novelist Norman Mailer, the actor Gregory Peck, the artist and peace activist Yoko Ono, and Peter and Elka Schumann. As Schumann recalled, the in-flight beverage service featured "beautiful vodkas."

The Schumanns had found themselves in this rarefied company because of their friendship with Sergey Obraztsov, a famous Soviet puppeteer. At the Kremlin summit, the other luminaries in attendance wanted to know what the Schumanns did for a living in Glover, Vt. Peter told them: "Papier-mâché."

Peter and Elka founded Bread and Puppet in 1963 on the Lower East Side of New York City, where they often enlisted neighborhood kids to help make masks and participate in shows. The troupe rose to international prominence for its 1968 show "Fire," a slow, wordless pageant about the atrocities of the Vietnam War that ended with a puppet of a Vietnamese woman dying by allegorical self-immolation. Bread and Puppet moved to Vermont in the early '70s — first to Plainfield, where the Schumanns were artists-in-residence at Goddard College, and then, in 1974, to the Glover farm that had belonged to Elka's parents.

Few of the radical experiments in rural living and art-making of the 1960s and '70s remain as robust and influential today as Bread and Puppet. The troupe counts among its disciples and alumni a lengthy list of acclaimed artists, including Julie Taymor, whose Tony Award-winning adaptation of The Lion King for Broadway made use of puppets and papier-mâché. Many past and present Bread and Puppet performers have launched their own theater companies, inspired by Peter's defiantly lowbrow aesthetic. His "Why Cheap Art? Manifesto," a ransom note-style paean reproduced by hand at the print shop on the farm, can be found in museums, university libraries and bathrooms the world over.

Bread and Puppet owes its longevity, in part, to its inclusiveness — anyone can show up on the day of the circus and jump in — and to the influence of Elka. She turned the massive dairy barn filled with Peter's puppets into a public museum, oversaw the Bread and Puppet Press, and generally acted as a stabilizing force to the tempest of Peter's creativity.

"He's a real narcissist," Dolan said, not without love. "Not a fake, low-grade one, but a real, charismatic narcissist." Eddie Haynes, a former puppeteer who now works as the groundskeeper for the theater, thinks Peter is fundamentally uninterested in the social dynamics of Bread and Puppet. "The goal of this place is for Peter to work," he told me. "He's not a cult leader. He's not here to teach."

- Luke Awtry

- Inside the Bread and Puppet Museum

Peter was born in 1934 in Silesia, a region of eastern Germany that became part of Poland after World War II. When he was 10, his family fled their home under siege from Allied and Soviet troops and escaped to a refugee camp. They subsisted on turnips and Peter's mother's sourdough rye bread — the same bread Peter bakes today at Bread and Puppet, using his mother's 160-year-old starter. At night, no lights were permitted in the camp, so Peter and his four siblings sat in pitch darkness and recited stories to each other from Brothers Grimm fairy tales, the only book they had managed to bring from home.

By the time Peter met Elka, in 1955, he was an art school dropout with vague but grand ambitions. Their first encounter was in a hospital room in Munich, where Peter was recovering from a bike accident he suffered in a recruitment stunt for a dance company he'd started with his childhood friend.

Around this time, according to a two-volume history of Bread and Puppet by theater historian Stefan Brecht, son of playwright Bertolt, Peter talked a lot about mounting a pageant in the tradition of the Oberammergau, an open-air play depicting the life and death of Christ staged once a decade by some 2,000 inhabitants of a village in the Bavarian Alps. But there were some problems with this idea, not least of which was that Peter didn't have 2,000 Bavarian villagers at his disposal.

By summer 1961, Peter and Elka, married with two children, had moved to the United States and were living with Elka's parents in Ridgefield, Conn., a wealthy suburb of New York City. In Brecht's telling, Peter did his best not to fit in with his new surroundings. He spent his days making hundreds of little human forms out of cement and plastic and papier-mâché. When he ran out of surfaces in the house, he would stash his creations in the oven, where Elka's mother was not amused to find them.

"My parents really had a hard time with Peter," Elka told Brecht. "They thought he was a real irresponsible and strange man."

Overheard at Bread and Puppet

- Josh Kuckens

- A giant papier-mâché hand in the Sunday pageant

The scale and complexity of Bread and Puppet's work have provided occasion for sentences that probably have never been uttered before. Such as:

"There's a question from inside the whale!"

"Want to be a frog landlord?"

"I have sausages, a baby and a gas mask. I think I'm all set."

"Can anyone replace me as a gate of Hell this Saturday?"

Heart of the Matter

- Josh Kuckens

- Bread and Puppet's Sunday afternoon circus

By the first weekend of July, the circus was slowly coming together. This summer's show, which Schumann titled "The Heart of the Matter Circus," included a skit about the destruction of pollinator habitat, featuring a brief musical interlude of Beyoncé's "Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)," and an act about youth activists in Montana who sued the state — and won — for violating their right to a clean environment. Still, Schumann found the whole thing wanting. "The acts are pretty mediocre political statements, because they don't dare to say anything," he told me. "They say wishy-washy little generalities."

But he was fond of one act, set to an accordion ballad, in which the performers careened around each other in a freewheeling dance, flapping pieces of cardboard and singing: "We are going to die! We are going to die! Today or tomorrow, it's life that we borrow! We are going to die!" Repeat.

The puppeteers had debuted this act during one of the first circus rehearsals of the season, to acclaim from Schumann. He liked their inventive use of cardboard. "So much better this way than with actual wings," he said. Ben Stieler and Ludivine Hipeau, who had come up with the skit, told me they saw it as a celebration of life in the face of the inevitable.

"I think it truly gets to the heart of the matter," Stieler said. "Like, why should we make the world better if we're all going to die?"

On the Saturday before the troupe's first performance, a group of puppeteers rehearsed the act in the circus field while Schumann and Dolan watched. The performers leaped and spun in circles with their cardboard like a flock of demented birds, an unabashedly weird display of abandon. Stieler stood in the middle of it, wearing a cardboard donkey head. When they had finished the last chorus of "We are going to die!" Schumann looked pleased. "Best message ever!" he said.

Dolan thought it needed something more. "I feel like you can make just a brief tie-in to climate change," she said. "How about having a single kid come in at the end and say, 'I'm a kid, and I beseech you: Do something about climate change now! Mobilize!'"

"I like it better without this," Schumann said. "Very definitely without."

But as the puppeteers rehearsed the skit one more time, Schumann changed his mind. "You guys!" he yelled to the puppeteers. "At the end, say: 'No! We are not going to die! Change the climate!'"

Some people weren't thrilled about this late addition. "I mean, we are going to die. It's, like, the basic truth," Hipeau told me later. "Can't we say the truth?"

How to Be a Garbageman

- Josh Kuckens

- Bread and Puppet alumnus Paul Zaloom and a puppeteer playing a garbageman

The first time I put on a papier-mâché garbageman head, I discovered an essential truth about Bread and Puppet, which is that everyone wearing a puppet head in a performance is visually impaired. My view of the outside world was limited to a centimeter-wide slit, which caused serious problems for me in the arena of knowing what the fuck I was doing.

Mark Dannenhauer, who has been part of the theater since the early '70s, gave me some helpful tips. His first time performing in a Bread and Puppet show was at Emmanuel Church in Boston, in 1971. His role was to sit in one of the church's upper balconies with his arms outstretched, wearing a giant puppet head and gloves coated in talcum powder. Over the course of 20 minutes, he said, he gradually brought his hands closer and closer together. When they were about six inches apart, he clapped them, releasing a puff of white dust.

"You have to move slowly and deliberately," he said. "Anything sudden or jerky looks really weird with a giant puppet head."

As it turns out, most normal motions look sudden and jerky with a giant puppet head. You can't simply turn this way and that, or the mask might slip out of position, leaving you blind. You sure as hell can't scratch an itch. You must, at all costs, resist the urge to sneeze. If you don't, you will emit a terrible noise, like a bomb detonating underwater, and you will know the taste of your own sputum.

I told Dannenhauer I appreciated his advice. "I've never done anything like this before," I said. He shrugged. "Who has?"

The garbagemen look like they enjoy a beer or four after work. They are the folk heroes of Bread and Puppet. During the circus, they sit on the sidelines with their potbellies and dungarees, getting up occasionally to pick up props left behind by puppeteers. Other garbagemen, like Bobby Cleverdon, embody the spirit of the garbageman by striving to do as little as possible.

Cleverdon came to Vermont in the 1970s to avoid being drafted in the Vietnam War. He has brown, leathery skin and a brown, leathery voice. Whenever he can, he hitchhikes the 30 or so miles to Bread and Puppet from his home in East Charleston. One of his hobbies is perusing old dictionaries to study changes in word usage over time.

"I found a definition in a dictionary with a publication date of 1942 that defines 'fascist' as 'a government with close collusion between government and large corporations,'" he said. By this definition and several others, Cleverdon believes we're living in a fascist country. I asked him how he adapted to this reality. "I've dropped out as far as I could do conveniently," he told me. "And I do things like Bread and Puppet, which won't change the world, but it satisfies my conscience, to an extent."

It was Sunday morning, and Cleverdon and I, along with the other performers, were unloading puppets from the school buses in the circus field to get ready for the performance that afternoon. At the 9 a.m. meeting, Schumann had declared that the Mother Earth puppet would be incorporated into one of the acts.

Mother Earth is a puppet in the sense that a megalodon is a fish. She is a behemoth contraption — her arms are white plastic sheets that billow in the wind and measure more than 100 feet when fully extended; each of her papier-mâché hands is big enough to cradle LeBron James. No fewer than 20 people are required to successfully operate her.

Before I donned the faintly musty mask and pillow gut of the garbageman in the circus that day, my task would be to help carry Mother Earth into the circus ring at the start of the act and unfurl her arms around the perimeter. At the end, we would bring her hands together so that her arms would encircle everyone in the act, which involved half a dozen small children and 11 adults, several of whom would be lashed together with a rope and one of whom would be inside a 10-foot-tall evil Uncle Sam puppet. Then, with everyone thus trapped in our embrace, we were supposed to exit the ring together, at a brisk pace and, in the case of the Mother Earth puppeteers, backward.

Pulling this off would depend on our ability to communicate with our fellow Mother Earth operators, most of whom we would not be able to hear or see. We had one rehearsal to figure it out.

I ended up on Mother Earth's left wrist, where I had an unobstructed view of the hand's interior. The inside was hollow and roomy enough for a little kid to climb in, with a scrap-wood frame that appeared to have been hastily pieced together. There were five of us on this hand, and lifting it off the ground still took some effort.

"Watch out for the sharp nails," my hand partner Isabella Donati-Simmons warned me as I tried out several grips, all of them awkward in different ways. When she isn't at Bread and Puppet, Donati-Simmons travels around British Columbia and replants forests cleared by commercial loggers. "I love being uncomfortable," she told me.

Another puppeteer on our hand, Hugo Crick-Furman, leaned against Mother Earth's palm. "I feel so held right now," she said.

The Embrace of Mother Earth

- Josh Kuckens

- A circus performance

The music for the circus act began. Mother Earth's moment had come. I ran to my station and promptly disassociated from my corporeal form. Things I remember: feeling the sun on my cheeks, wishing I had applied more sunscreen, realizing I'd never taken off my sun hat, surveying other Mother Earth operators to see if anyone else was wearing a hat, realizing no one else was wearing a hat, feeling embarrassed to be the only person wearing a hat, feeling embarrassed at my own embarrassment. To be self-conscious while holding the left wrist of Mother Earth! I was nothing, a tiny cog in a glorious machine.

Then the act ended. As the hands of Mother Earth closed around the performers, the panic I'd managed to keep at bay flooded my body. The Mother Earthers were moving faster than the people corralled in her arms. I was in imminent danger of trampling the small child behind me, but if I stopped moving, I would be steamrolled by the hand of Mother Earth. As I reached back to push the kid out of my path, a gust of wind whipped Mother Earth's sleeve and knocked my hat over my eyes.

"Slow down! SLOW DOWN!" I yelled, to no effect whatsoever. I had a moment of sudden clarity. Damn, I thought. So this is what it's like to die in a stampede.

Then a series of small miracles happened. Another wind gust blew my hat off my face. Donati-Simmons, who had been next to me this whole time, let go of the hand and slipped away, ninja-like, under the sleeve, sparing me a few critical inches to avoid colliding with the kid. A puppeteer squeezed herself between us, and somehow she and the kid managed to duck out together unharmed.

Like a brief violent thunderstorm, it was over. I'd come within seconds of maiming a child, but there was no time to mull that over. I had to go be a garbageman.

A Grave in the Forest

- Luke Awtry

- A piano in the pine forest

A short distance into the pine forest above the circus field, just beyond the remnants of a Baldwin piano that has been left to molder in the elements, is a cluster of little wooden huts, sculptures and shrines dedicated to deceased members of the Bread and Puppet community. Elka is buried in a small clearing nearby, beneath a mound covered in wildflowers. At the foot of her grave is a bench, where Schumann often sits in the evenings and smokes a cigar. His grave, as yet undug, is next to Elka's.

Every Thursday after dinner, the theater observes a ritual of remembrance in the pine forest. There is no formal program. People simply sit in the woods, sometimes with a beer, and contemplate the dead. Occasionally, the theater holds services when someone close to Bread and Puppet dies. Toward the end of July, Dolan and two other alumni organized a memorial for Nabila Schwab, who was part of Bread and Puppet in the '90s and taught many people, including Dolan, how to walk on stilts.

- Luke Awtry

- Memorial for Elka Schumann

After rehearsal one morning, I went for a walk in the pine forest with Dolan and Schumann to scout a location for Schwab's memorial site. Here and there, Schumann stopped to size up a patch of earth. Being in the pine forest, he said, is overwhelming. "It's not just my wife. People who we knew since the early '60s — they're in here. People we depended on."

As we walked back toward the circus field, Dolan asked Schumann why he kept making shows. "You're right," Schumann said. "Why not retire? I have a beautiful porch. That's all you need for dying."

"For dying, or for retirement?" I asked. "Or is that the same thing?"

"Also interesting," Schumann said.

'He Can't Let Go of His Work'

- Josh Kuckens

- Peter Schumann playing violin

While most of the puppeteers were performing at an arboretum in the Hamptons in late July, the small group that stayed behind held a modest pageant rehearsal. That morning, Schumann had gone to a doctor's appointment. He told us he'd return by 3:30 p.m., but he never showed up.

Back at the farm, we learned that his doctors had discovered he'd likely had another stroke in the past couple of weeks, and they wanted to keep him overnight at Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital in St. Johnsbury. Schumann refused. The next morning he was back in his studio, painting another bedsheet. He was not in a good mood.

"Humanity is so stupid, it's unbelievable. At the hospital, they use plastic for everything, and everything they use, they throw out. Why not die in there? How beautiful that would be," he said, applying a shade of green reminiscent of mint toothpaste to the sheet. He was painting a village surrounded by rolling hills; above the hills and the village was a sky with red banners and the words "Heart of the Matter."

After Elka's death, Schumann said, he thought he was done living. "Finished," he said. "Bye-bye, Schumann." He picked out the trees and the telephone cords by which he would do himself in, and then he decided not to go through with it.

"Every time he talked about hanging himself, I'd say, 'I don't believe you,'" Dolan told me. "He can't let go of his work. He wants to work until he drops. He's just an animal that can't stop making things."

Schumann also feels some responsibility to the world he and Elka created, which he fears will implode without him. "Before I go into the graveyard, I should try to console some of the things that are pretty bad here," he said. "Make it so that it can reasonably continue. It's not so clear that it can be continued."

But what Schumann believes will endure is not a style of theater-making or a barn full of puppets but the accumulation of quiet, fleeting moments that make up a performance — the position of a cloud in the sky, the angle of the late-afternoon sun as the papier-mâché hands slowly move through the air above the meadow. "It's almost like saying, when a poet dies, is there a legacy besides his poetry?" Schumann asked. "Can the audience be part of the legacy?"

In one of the shows this summer, the performers lie on their backs on the dirt floor of the barn theater with a life-size cardboard body on top of them. They grab fistfuls of dirt and slowly sprinkle it over their puppets, an enactment of burial, filling the barn with the echoes of dirt trickling over cardboard. After a while, it sounds almost like rain, a requiem as they commit their puppets to the earth.

"That is a sound that doesn't exist culturally," Schumann said. "But that is a sound that this little audience deserves."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.