- Pamela Polston ©️ Seven Days

- Heidi Broner with a painting in progress

Heidi Broner nearly didn't become an artist. Chalk it up to teenage rebellion. Growing up on Long Island in New York, she didn't especially get along with her father, whom she described as "a really good abstract painter." Among four daughters, Broner said, he "picked me out" to follow his métier. She wasn't having it.

But luck — or fate or maturity — intervened and, in her thirties, Broner changed her mind. "I really did want to have a good relationship with him," she said, "and I did want to pursue art."

Today, the Calais-based painter, 69, is widely known for her depictions of people at work, particularly those in the trades. That interest has strong resonance now, a time of universal shortages in the labor force.

A large piece recently exhibited in the "20/20 Hindsight" exhibition at Art at the Kent is a stellar example. Titled "Spreading Cement," it features an African American man, clad in jeans, a white sweatshirt and a backward ball cap, doing just that. His face is in profile; he's intent on his job, not self-consciously posing.

The figure is exceedingly well rendered, from his posture to the drape of his clothes. But in a Broner painting, realism bumps gently into the transcendental. In this case, a void surrounds the worker, as if he's spreading cement at the edge of the world.

This mist of pastel hues suffused with light is painted so exquisitely that it cannot be called nothingness, though. Here, "absence" has a presence, if an ethereal one. Broner captures what being lost in thought looks like, as if her human subject produces a corona of concentration that only she can see.

"Heidi has been on our radar for a long time," said Nel Emlen, one of three cocurators who assemble the annual Art at the Kent exhibition. "We pool our ideas and go through them once we choose a theme. When we decided on the theme for this show [honoring makers from the historic site's past], Heidi immediately came to mind."

Emlen appreciates Broner's "ability to tell stories about the workers through the painting," she said. At the exhibition, "people kept circling back to Heidi's work and really enjoying it."

Emlen added that more men commented on the work than is typical. One gentleman even said, "I'd like to see a painting of me at work," the curator recalled.

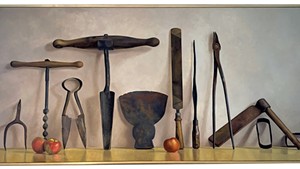

- Courtesy Of Heidi Broner

- "Order Out of Chaos"

Broner had 24 paintings in the "20/20" show — many of them measuring a few inches rather than feet. By no means does she paint only male laborers. A work called "Order Out of Chaos" freezes a waitress mid-bustle as she prepares tables for a lunch rush.

Like "Spreading Cement," this painting includes relatable details: red ketchup squeeze bottles, paper napkin rings and the server's practical Danskos. But Broner trades a cluttered café background for that celestial ether. The tables seem to float on a cloud.

Broner doesn't always paint workers. "I particularly like going to a roller derby," she said during a studio visit. "I like people in a parade, a balloon vendor." She also likes to paint rocks and animals.

That said, the work in progress perched on her easel last week features a young man bent over a pail and a small stack of bricks. Broner's photograph of the worker — she generally shoots first, paints with acrylics later — reveals a messy construction site. The painting eliminates that distraction.

"I kind of approach a painting as if it's an abstract," Broner said. "I'm not attached to the original photo; I can move elements in the space, change the colors. I know, to a lot of people, the face says a lot about the person, the personality. But I see the body — it says so much about who they are.

"I like people, seeing their vulnerabilities and strengths," she continued. "It's just delicious to look at people."

Broner herself is slender, graceful, composed. Greeting a reporter at the rural home she shares with her husband, Mason Singer, she claimed to be nervous but warmed to talking about her life's path — both to Vermont and to making art.

- Courtesy Of Heidi Broner

- "Free Pile"

Perhaps the nonchalant entrance of her cat broke the ice. Samson, a yellow-orange fellow, has a configuration of fur between his eyes that gives him a permanent don't-mess-with-me scowl. It's impossible not to smile in his presence.

Broner said she left high school early and eschewed college. She sang with a Renaissance music group and worked with theater companies — "I gravitated toward making props and set pieces," she said. She made puppets for an opera about Frida Kahlo. She worked at a macrobiotic restaurant in New York City.

After visiting a friend who was attending Goddard College, Broner moved to Vermont at age 22. "I felt like there was so much to do in New York, but it was about watching other people do stuff," she said. "I wanted to do my own stuff."

She landed a cooking gig at Montpelier's Horn of the Moon Café. Her theater experience led her naturally to Bread and Puppet Theater, the Glover-based company with which she would work for 20 years.

She also began taking life drawing classes in Montpelier. "I saw the models got paid, so I started art modeling, too," Broner said. "It put me in an environment that made me realize art was a legitimate pursuit — and that I already was [an artist]."

She worked for a time as a freelance illustrator but barely scraped by, she recalled. In 1999, a friend told Broner about a job that would pay better: granite etching. It's a profession she practices to this day, though she's gone from working for four granite sheds to just one.

Broner admitted that being the only woman in a male-dominated workplace has its challenges, but she likes the "straightforward, simple" task. And etching led to an epiphany: "Because I worked from photos for the gravestones' [portraits], I realized I could work from my own photos," Broner said. "It freed me up to realize I could make art that I liked."

Her experiences in the granite sheds also introduced Broner to the men-at-work motif. A recent painting titled simply "Granite Polisher" illustrates her ongoing fascination with the body language of a person focused on a job. We see an older man from behind, slightly slumped, clad in a long apron and sturdy work boots. Black, yellow, red and green electrical cords snake through the composition. Of course, the distance is a haze.

Broner remembers when she became attracted to scenes of laborers doing their thing. "One day I was going to work at one of the granite sheds, and there were these guys who were patching some asphalt. Steam was rising — it was a cold day," she said.

She had a camera with her, but it was out of film. "I went to the store, bought some film and took a lot of photos of them," Broner recalled. "I would watch them for a while to see what they were trying to do.

"I just really enjoyed the subject," she continued. "I still do."

- Courtesy Of Heidi Broner

- "Spreading Cement"

The cement spreader painting, it turns out, has a special significance to Broner. "When my father was dying in New York City — I was helping to take care of him — I wanted to show him a photo of the painting [in progress]," she said. "I couldn't get it to him before he became unresponsive."

Broner had a hard time returning to that painting after her father passed, but with encouragement from a friend, she eventually did. "I kept painting out more and more of the background; it was like my father's death, teetering on the edge, his experience of dying," she said.

Yet death is not what she has in mind when painting her figures today. "When I work from a photo, it's not a still. There's a stillness around them, but I like to see their focus," Broner said. "It's also an awareness. I think that we have an ability to focus on something but also an ambient awareness of what's around you."

If Broner's paintings effectively exalt workers — the people who fix our streets, climb utility poles, lay bricks — their point isn't just to witness these normally overlooked people, she suggested, but to show us something about them.

"You see the results [of their work,] but not how it gets done," she said. "This is how it gets done."

Correction, October 21, 2021: A previous version of this story misidentified Mason Singer's profession.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.