- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Russ Bennett

Russ Bennett sits on the small front patio of his modest mountainside house in Moretown. Strains of bebop jazz can be heard faintly from within, rolling down his gently sloping lawn and adding to the serenity surrounding him. That tranquility contrasts sharply with the difficulties of getting to his home, a journey that entails navigating a series of increasingly steep, winding and narrow dirt roads, inevitable wrong turns and one angry dog with an apparent thing for chasing lost journalists. Bennett is a hard man to track down. Wizards usually are.

That he is staring into the MacBook on his lap does little to diminish his mystical aura. He's probably Skyping with his twin brother, Gandalf. Bennett isn't wearing flowing robes. He's a jeans and T-shirt kind of guy. Still, his long white hair and matching beard make him a dead ringer for Tolkien's iconic mage.

You won't catch Bennett casting spells or battling ancient demons. But he is a magician of a high order, even if his sorcery is more of the man-behind-the-curtain variety. The founder of NorthLand Visual Design & Construction, Bennett, 66, is a master builder and a genius at morphing the ordinary into the extraordinary. His design work in Vermont has helped transform businesses. His work on Phish mega-festivals — as well as on the Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival in Tennessee — has served as an inspirational template for modern music-festival culture.

- courtesy of Russ Bennett

- Arch at Bonnaroo

Examples of Bennett's unique brand of architectural alchemy can be found all over the country, from the steampunk-chic aesthetic of the Magic Hat Artifactory in South Burlington to the rustic charm of Red Hen Baking and Nutty Steph's in Middlesex to the eclectic Outside Lands festival in San Francisco. Or you could just take a look around his yard.

Bennett's plain two-story house is, as mountaintop lairs go, unremarkable. The view of the eastern face of the Green Mountains from the patio, however, is spectacular.

"When I built the place, you could see Mansfield," he says, pointing to a stand of trees at the edge of the lawn. "Someday I should probably cut those down." As he waves his hand, I half expect the trees simply to vanish. Then his hand drifts slightly left. "Those are pretty cool, though."

A few yards in front of the woods stand two tall, straight trees. One appears to have died some years ago; at its top hangs a spherical metal contraption that calls to mind a gizmo from a 1950s sci-fi movie. Midway up the adjacent tree, hang-glider-size turquoise "leaves" circle the mostly limbless trunk.

The sphere and leaves are, Bennett explains, among his "leftovers" from various music festivals and installations — including all 10 Phish festivals. The leaves are from Coventry in 2004. Hidden all over the woods surrounding his house are "lemonheads," the semi-creepy lemon-topped masks from 1998's Lemonwheel in Limestone, Maine.* When you catch them in your peripheral vision, they almost seem to be watching you. Perhaps they are.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Russ Bennett in front of giant mirror ball from Super Ball IX

On the southern end of Bennett's property, large cartoon hands point the way into the woods. Or, perhaps, to Narnia. There's a funky outbuilding from some festival that Bennett uses as a bunkhouse. Its interior walls are covered in the scrawled signatures of past guests. There's a 20-foot-tall mirror ball from Super Ball IX, the 2011 Phish festival in Watkins Glen, N.Y. Members of Phish and other local musicians have been known to jam inside the sphere because of its near-perfect acoustics.

Elsewhere in the yard rests a 15-foot-long pencil that used to sit in front of Bennett's Waitsfield shop. And there's a hammock, which is just an ordinary hammock — even wizards need naps.

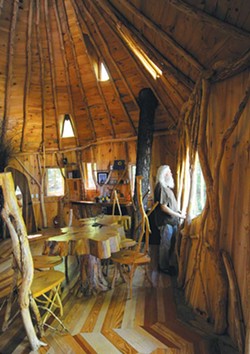

The crown jewel of this magical kingdom is Bennett's tree house, situated two stories up in a thick grove. When you encounter it in the woods, it takes a minute to register what you're looking at. With an aesthetic ripped from the pages of The Hobbit, the tree house is simply astonishing. And, in true Bennett fashion, it is both a product and a reflection of its surroundings. The structure was made almost entirely of lumber from his land. In an effort to "honor the wood," he processed the timber as little as possible, leaving natural bends and knots. There isn't a straight line or right angle anywhere.

While Bennett's projects are often whimsical and infused with style, the builder seems to have a functional principle in mind: facilitating social interaction. That, and making things look really cool. Those tenets hold whether Bennett is working on smaller projects, such as sprucing up the Ben & Jerry's scoop shop in Burlington, or larger ones, such as constructing city-size music festivals and designing and building lavish homes for clients throughout the Green Mountains.

Bennett even plans to make his woodpile a piece of functional art. As he leads a reporter around his property, he notes the huge mound of split logs piled on his back lawn.

"When I get around to stacking that, I'll do something fun with it," he promises. Then, inadvertently summing up his design philosophy, he adds, "If you're going to do the work anyway, you might as well put the effort in to make it interesting."

Crystal Balls

- courtesy of Russ Bennett

- Oompa Loompa buskers at a Phish show, circa 2004

Any discussion of Bennett's work should probably start with Phish and their festivals. Actually, it should start with Bread and Puppet Theater. Many artistic roads in Vermont seem to lead back to Glover.

Bennett grew up outside Manhattan and moved to Vermont in 1971. He worked as a builder and founded NorthLand in 1978. After seeing a Bread and Puppet pageant at Goddard College in the early 1980s, Bennett began working with the radical avant-garde theater troupe. He counts founder Peter Schumann as a crucial inspiration, both artistically and politically. On his website, Bennett describes himself as a "designer, builder, sculptor, social activist and planner within his community" — all qualities embodied by Bread and Puppet.

"Those influences are forever," says Bennett of his time with Schumann. "People use the word 'genius' all the time, like they use 'wow' and 'beautiful.' But he's a true genius."

- courtesy of Russ Bennett

- Bobblehead at Bonnaroo

Among the many lessons Bennett took from Schumann — and perhaps the most impactful on his own artistic worldview — is that confusing people can be a good thing.

"You hear people say oftentimes, 'I don't really know what that was about,'" Bennett explains. "What that means is, you've done some really good stuff. You've made people think about something."

Bennett is prone to digressions. Explaining how he got from puppets to Phish, he riffs on metaphors involving highway infrastructure, food systems and George W. Bush, among other topics. Honestly, it's a little confusing. But then, what are a magician's greatest allies if not deception and sleight of hand?

"The brain is an editor of information, and not just through your eyes," says Bennett. "We can really communicate so much faster and on many levels using different methods and senses." Baker-puppeteer-activist Schumann would no doubt agree.

- courtesy of Russ Bennett

- Windmills at Outside Lands, circa 2008

Bennett worked with the theater group until the mid-1990s, right around the time that Phish came calling with an idea for a music festival.

"They wanted to do something different," says Bennett. "I had no idea."

The idea was the Clifford Ball, a weekend-long fest at the former Air Force base in Plattsburgh, and the first of the band's 10 mega-festivals. It would draw more than 70,000 people. Bennett's task was essentially to create a temporary city on the base — one nearly four times the size of Plattsburgh and, for that August weekend in 1996, the ninth largest in the state of New York.

"We're going to have a city, so we thought we should have a park, a place for social congress to happen," says Bennett. He and his crew created Ball Square, a carnival-like city center. They populated it with buskers and street performers, some from Bread and Puppet. Bennett enlisted a veritable army of artists and builders to construct the city and give it what he likes to call "an artistic flavor."

Among those artists was Lars Fisk, a Vermont-born sculptor now based in Brooklyn. He has worked with Bennett on every Phish fest — one of his sculptures, titled "The Barn Ball," is the cover image of Phish's 2002 album Round Room. Over the years, Fisk and Bennett have developed a close working relationship. But it didn't start out that way.

- Courtesy of Russ Bennett

- Phish show, Atlantic City, 2012

"It was difficult at first," says Fisk of working with Bennett. "He has such a strong leadership sensibility. So for us to become collaborators on a more intimate level and become comfortable took a lot of work. Once we arrived at that point, it was a really great experience."

Perhaps the highest point of that experience was the 2003 festival in Limestone, Maine, named simply It. Fisk calls that fest "the pinnacle" of his Phish collaborations with Bennett.

"We developed an idea called 'the sunk city,'" Fisk says. The concept, he explains, was the postapocalyptic ruin of a city that had been allowed to sink back into the earth. "You had a commercial-minded society that was somewhat like Times Square or Las Vegas, all of which was half submerged in the ground, so you would only see the top portion of whatever was left of the city," he recalls. "It was pretty cool."

Fisk worked with Phish bassist Mike Gordon and designer Scott Campbell to develop nonsensical verbiage for Times Square-esque signage on the festival grounds. Bennett created a system of catwalks that wound through, over, under and around the recessed cityscape.

"It felt like nature had taken over again after civilization had sunk into the muck," says Fisk, who cites the half-sunken Statue of Liberty from the iconic final scene of Planet of the Apes as an inspiration.

"Russ is demanding," says Burlington sculptor Kat Clear. "But it's only because he has an overactive imagination. He sees possibilities where sometimes no one else does."

Clear is an acclaimed local metal artist. She's worked with Bennett on numerous projects, including three Phish festivals. Among her contributions to Super Ball IX was an after-hours club designed to replicate the innards of a human-scale pinball machine.

"Basically, it functioned as though you were the ball in the pinball machine," Clear says. "It was as close as you could be to being literally interactive art. Russ pushed me further in making this, the most epic thing I think I've ever made."

"Phish is like free-jazz collaboration," says Bennett, comparing his festival creations with that band to his work at Bonnaroo. He's served as the head of visual design for the latter since its inception in 2002. "Phish might have a particular viewpoint or direction that the name [of the festival] might be evocative of," Bennett notes. He and his crew try to represent that vision and play along by threading other artistic disciplines through the tapestry of a Phish festival.

At a festival like Bonnaroo or Outside Lands, featuring a wide array of bands of various genres, Bennett says the design might be more eclectic, less focused on a single theme.

- courtesy of Russ Bennett

- A firefly at Bonnaroo, circa 2003

"At Bonnaroo, we have a jazz tent — which, when you're in it, you would never believe you were on a farm. It's like going into a giant Vanguard experience," he says, alluding to famed New York City jazz club the Village Vanguard.

What these festivals have in common is another Bennett specialty: inspiring the suspension of disbelief.

"And that's a form of art, as well," says the designer. "In both instances, I think people are living at a higher level than they live the rest of their lives, and they are desperate to live that way."

Though his best trick may be world building, Bennett bristles at the suggestion that he's conjuring an alternate reality.

"I resist the notion of 'going back' to the real world," he says. "It's all reality. None of this is not real. Something might be aberrant from your day-to-day life. But it's all real."

Second Drafts

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Russ Bennett in his Moretown tree house

Bennett's tree house is emblematic of his best and most creative work, much of which can be found in Vermont. It is warm, welcoming, mysterious and awe-inspiring. And it is a place for "social congress," as he calls it. Bennett often invites guests from various parts of his life to come and sit on the tree house deck, have drinks and share ideas.

"You have to have bad ideas, and you have to let them out," he advises. "Because the more you try not to have bad ideas, the more they just get in the way."

Bennett also lets local community planning groups use the tree house for meetings. "The only stipulation is that they have to agree to have better ideas here than wherever else they would have met," he says.

The tree house is representative of Bennett's commercial work in yet another way: Impressive as it is, it is an eternal work in progress.

"There is always some way to make it a little better," he says, running his hand over a window frame made of boughs.

Bennett designed and built the original Magic Hat Artifactory, the brewery's retail store in South Burlington. Playing on the company's theme of melding "alchemy and science," the space, which he has since helped renovate, is cavernous, dark and esoteric. It contrasts starkly with the bright tasting room/gift shops that are a craft beer industry staple. The Artifactory features an extensive tour ramp that, after a number of twists and turns, deposits visitors directly above the production floor.

"He's creative as hell," says Magic Hat cofounder Alan Newman, a serial entrepreneur who is a bit of a wizard himself. Newman also founded or cofounded Gardener's Supply and Seventh Generation. He is currently co-owner of the nightclub Higher Ground.

"He has similar habits as me," Newman observes of Bennett. "Tell him it can't be done, and get the fuck out of the way."

Newman says Bennett's most important skill is often overlooked: execution. "Anybody can have cool ideas. But to execute them well, to bring them to life, is special," he says.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Foam Brewers, Burlington

Bennett understands that a project is never truly finished. He recently designed and built the interior of Foam Brewers on the Burlington waterfront. It's an eye-popping room dominated by exposed brick, wood beams and reclaimed metal — the last fashioned by Clear. The centerpiece is a bar that, unlike typical straight or horseshoe-shaped models, undulates from the back wall. The idea is to encourage socializing, a Bennett hallmark. If you're sitting at the bar — or at similarly shaped tables around the room — you don't need to lean in to talk to someone. Because of the curves, patrons are naturally situated to interact.

Though the brewpub opened in April, Bennett regularly checks in to see what needs improvement. "How a space behaves has a lot to do with how it succeeds," he says.

"Russ is in here constantly," says Foam cofounder Todd Haire, the former master brewer at Magic Hat. "He'll get off a red-eye [flight] and come straight here just to check in and see how things are going."

"The greatest paintings have been painted over many times," says Bennett, explaining his habit of following up with clients. "You're just looking at the last iteration."

Right now, he's in the development stage with another iteration: of the façade at the ECHO Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, just across Waterfront Park from Foam. Bennett also created an interactive exhibition for children called Champ Lane inside the science center.

"It's very much a hardscape, urban all the way around," says Bennett of ECHO's current exterior. "People walk by it, but they're not within it."

He won't divulge specifics of how the renovation will look. But, if his résumé is any indication, the results will be a marvel of both form and function.

"We can help through the use of art and good planning," Bennett explains. "So that when you look at the building and the things around the building, you have already entered it; so that the message about water and science and fish and all that stuff is more present on the outside.

"It's like stacking the wood," he continues. "You can just stack it. Or you can make it into different shapes and make your eye run across the landscape a little bit. You can take all the work that you're going to do and do it with an artistic flavor," Bennett concludes. "And it will return more."

*Correction, September 28, 2016: An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of the 1998 Lemonwheel Phish Festival. It was in Limestone, Maine.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.