- Caleb Kenna

- François Clemmons

Once upon a time, there was a nice man who lived in a nice town called Middlebury. He lived in a quiet little house on a quiet little street, which he shared with a dog named Princess, who was also little, but not always quiet. The man's name was François Clemmons. That's a fun name, isn't it? Let's say it together: Frahn-SWAH CLEH-mons.

Because he was so kind, Mr. Clemmons had lots and lots of friends all over the world. He also had many children. Now, these weren't his children like you are your parents' children. These were what he called his "cosmic children," who came from other mommies and daddies and were drawn to him because he had a talent for making people feel better.

A talent is something that you're good at doing. Mr. Clemmons was talented at many things, but especially at helping his cosmic children through hard times and lifting their spirits. Most of those children were barely children at all, but almost grown-ups. They were students at a school called Middlebury College, where Mr. Clemmons was an artist-in-residence for many years. Do you know someone who helps you when you're feeling blue? Stop and think about that person for a minute. Who did you think of?

Sometimes Mr. Clemmons made people feel better by telling stories. He had lots of stories, and he loved to share them. Mr. Clemmons could spend hours and hours telling stories, so sometimes you needed to give him a lot of time. But that was OK, because his stories were very entertaining. They were so good that he collected them in a memoir called Officer Clemmons that you'll soon be able to buy in bookstores. A memoir is a book in which someone tells you about their life. Mr. Clemmons had a very interesting life filled with lots of joy. But there were many sad times, too.

Mr. Clemmons spent a long time writing his book. But his favorite way to tell stories and lift spirits is by singing. He has a beautiful singing voice, a soaring tenor that he has shared with people all over the world, in places like New York City and Germany and Japan. He sang in famous concert halls and majestic churches and fancy theaters.

But he also might sing to you while you were just sitting there having a conversation in his living room. If you called his telephone and he wasn't able to answer, Mr. Clemmons might sing to you then, too, in an operatic outgoing message. Isn't that funny?

Once, in 1976, some nice people gave Mr. Clemmons a Grammy Award because he sang so well on a recording of an opera called Porgy and Bess. A Grammy is a special prize given to the best singers and musicians in the world. In 2019, a man named Phil Scott gave Mr. Clemmons the Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts because he helped so many people in Vermont by singing to them and teaching them to sing.

"I am pleased to name François as the winner of this year's Excellence in the Arts award," Gov. Scott proclaimed. "His renowned musical talent and years of service to his community made him the perfect choice. Congratulations, François, and thank you for making Vermont proud."

Isn't that nice?

Now, you might be wondering how Mr. Clemmons got to be so good at making people feel better. That's one of his favorite stories to tell.

You see, Mr. Clemmons once had a very special friend. His name was Fred Rogers. Almost every day for more than 30 years, Mister Rogers visited with millions of boys and girls through his television show, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." Mr. Clemmons was on that show, too. He played a singing policeman called Officer Clemmons. He was one of the first black regular cast members on an American children's TV show in history, something he is very proud of.

Not long ago, some creative people made two movies about Mister Rogers. One of them was a 2018 documentary called Won't You Be My Neighbor? A documentary is a movie that tells a true story by interviewing the people who lived it. Mr. Clemmons had very nice things to say about his friend Mister Rogers in that movie. And he looked very nice in his bright, colorful shirt and the turquoise jewelry that he always wears.

The second movie was called A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood. It came out in November, right around Thanksgiving, and starred a famous actor named Tom Hanks. It was not a documentary but a drama based on an Esquire magazine article about Mister Rogers called "Can You Say ... Hero?" by a wonderful journalist named Tom Junod. The style of the article you are reading right now is also loosely based on Mr. Junod's Esquire story. Can you say "pastiche"? (Please don't say "lawsuit," Mr. Junod.)

People liked both of the Mister Rogers movies. In fact, a lot of people think A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood will win Oscar awards — those are like Grammy Awards but for movies. Mr. Clemmons liked that movie, too. He said that Mr. Hanks did a good job pretending to be his friend Mister Rogers and that director Marielle Heller made a classic feel-good movie, a real tearjerker. If you saw it, you probably got choked up, too. And it's OK to cry, isn't it?

But, as much as he enjoyed the movie, Mr. Clemmons thought something important was missing: Officer Clemmons. And that made him sad. Because, to understand the story of Mister Rogers, it's important to know the story of Mr. Clemmons. And that, neighbors, is a very good story indeed.

I Like to Take My Time

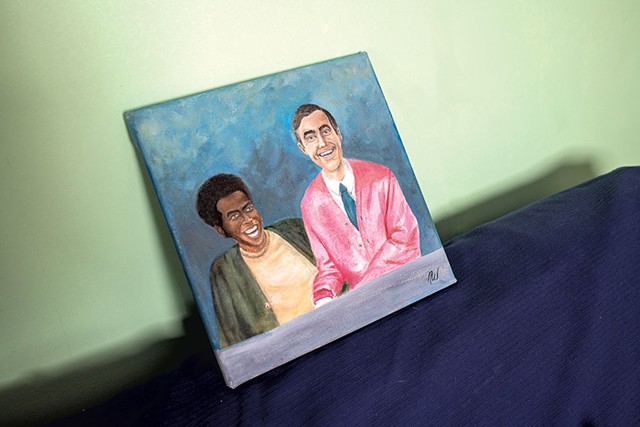

- Caleb Kenna

- Portrait of François Clemmons and Fred Rogers

François Clemmons isn't always great about returning messages. While he's not exactly a Luddite, the 74-year-old lacks a certain facility with modern tools such as cellphones and email. Fortunately, he's worth the wait.

Back in November, I had been trying to reach Clemmons for nearly a month. I'd worked any channel I could find, official and otherwise, with no real success. I came this close to giving up and telling my editors, tail tucked between my legs, that the profile we'd planned on the man was dust.

Then, lo and behold, one night around dinnertime, my phone rang, displaying a Middlebury number.

On the other end was a kind voice I'd heard countless times as a child. It had never occurred to me that I would still know — still feel — that voice more than three decades later, as a 41-year-old man. Yet here it was, as clear and warm as afternoon sun shining on the brown-and-orange hooked rug of my childhood living room in Bangor, Maine, where I'd first heard it on TV.

"Is this Ben from Seven Days?"

"It's Dan, but yes," I responded, grinning in recognition of Clemmons' voice but also because he'd called me Ben, and not for the last time. "Hi, François."

Clemmons proceeded to apologize profusely for taking so long to get back to me. The part-time assistant who helps him stay organized had noted my final Hail Mary email just that afternoon and urged him to call me. Even though Clemmons is retired, he's always busy, he explained. Between the award from the governor and the swell of Mister Rogers interest ahead of the Hanks movie, his phone had lately been ringing off the hook. I told him not to worry; I was just happy he'd called.

"Oh, good!" he said. "Now, what did you want to talk to me about?"

Befuddled, I paraphrased the raft of pitches I'd already sent him via email and voicemail but managed to explain that what I really needed at that moment was to arrange an in-person interview.

"Oh, sure, sure," Clemmons said absently. "I suppose you'll want to talk about Fred," he continued, without directing a shred of resentment or fatigue at one more nameless journalist — another Ben in a sea of Bens — who was calling to talk to him about Mister Rogers. In fact, he was almost laugh-singing: "They all want to talk about Fred!"

Then, without skipping a beat, he asked, "Can you come tomorrow?"

It would take some juggling, but I could.

"Wonderful!" he said. "And do you have some time now?"

I Like to Be Told

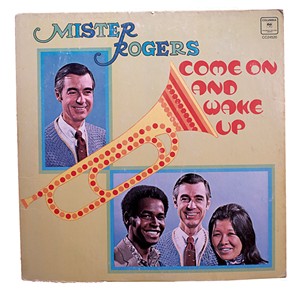

- Caleb Kenna

- A 1972 album

There's a scene in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood where Lloyd Vogel — the fictional stand-in for Esquire journalist Junod, played by Matthew Rhys — is dumbfounded to receive a call at home from Fred Rogers only hours after he submits a formal interview request to Rogers' handlers. When Vogel clumsily explains he called to arrange an interview time, Rogers responds matter-of-factly, "You have me right now. So what did you want to talk to me about?"

Watching that scene in the theater, I couldn't help but notice the similarities to my first call from Clemmons — minus Rogers' promptness. Later in the same scene, Rogers tells Vogel that the most important thing in the world to him in that moment is talking to Lloyd Vogel. That resonated, too.

Clemmons considers himself a devout Rogers disciple, a carrier of his legacy and, in his way, a successor. These are duties he holds solemnly, but also joyfully. It helps that he's immensely suited to the job, albeit in a more flamboyant fashion than the gentle, buttoned-down Rogers.

While Clemmons prefers bright, shiny kaftans to knit cardigans, he resembles his friend and mentor in striving to be present in his interactions to a degree that seems almost impossible. In conversation he's insightful and funny, and he asks questions with genuine interest. You don't interview François Clemmons; you converse with him. And when you converse with him, you're made to feel as though you are the most important thing in the whole world. Because in that moment, to him, you are.

"François has a sense of genuine kindness and unconditional love that seems to have no limits or boundaries," Adeline Cleveland, one of his hundreds of "cosmic children," wrote via email. "When I'm with him, I laugh hard, reflect deeply, listen closely and learn so much not only about his life and story but about how I want to be."

Cleveland, 28, spent her teen years in Middlebury and studied dance at the college, from which she graduated in 2013. She now lives in North Carolina but visits Clemmons whenever she comes home. "He reminds me not only through conversation but through example that we only have this one life to live," she continued. "There's no time to mess around or to hide your light from the world."

Clemmons' intense presentness can feel a little unsettling at first. But you'll have time to get comfortable, because conversations with him have a way of taking a while.

For example, that first phone call to schedule an interview lasted a solid 90 minutes. In it, we touched on everything from the scourge of emboldened racism under President Donald Trump to the sheltered worldviews and surprising personal struggles of some of Clemmons' Middlebury College students to my personal family history to, of course, Mister Rogers.

Clemmons is nothing if not thorough. Fun fact: The original manuscript of his memoir was 6,000 pages. With the help of colleagues at Middlebury and, later, professional editors, it's now a modest 288.

For every question you ask him, he provides context on top of nuance on top of the occasional dirty joke. Clemmons seems to view everything in his life as a series of long, interconnected roads on which all are welcome — and that all lead back, eventually, to a certain famous neighborhood and its most famous resident.

This Is My Home

- Caleb Kenna

- François Clemmons At Home

Clemmons lives in an unassuming house in a sleepy neighborhood a stone's throw from the college he served for 15 years. On the afternoon I visited him, the only indication of the eccentric resident within was the Toyota Prius parked in an open garage. Though he hardly drives it these days — Clemmons suffered a pair of strokes in 2018, which limited his mobility — the rear of the hybrid is festooned with colorful, politically progressive bumper stickers and sports a vanity plate bearing his well-earned nickname: DIVA MAN.

Inside, his home is busy and cluttered, but pleasantly so. Rare is the wall space devoid of some framed picture or memento from his past: an old black-and-white portrait of a skinny Clemmons in his twenties and another of his high school vocal group; glossy posters of the Harlem Spiritual Ensemble, the globe-trotting singing group he founded in the 1980s; flyers from numerous concerts at Middlebury College during his tenure as the director of the college choir and the Martin Luther King Spiritual Choir, the latter of which he founded. Plenty of Mister Rogers ephemera hang around, too, including photos and the odd handwritten letter.

Seated in a large, comfy chair in his living room with Princess, his pampered 10-year-old Tibetan terrier, at his feet, Clemmons carried himself with an air befitting the nickname DivaMan — or, as he's sometimes called, DivaBuddy. But his is a benign and calming sort of confidence, more ego-mystical than egotistical.

With little prompting, Clemmons launched into his life story, from his birth in Birmingham, Ala., to growing up poor in a rough neighborhood in Youngstown, Ohio; from singing in school and church to the growing realization that he was gay and his parents' rejection of him for it; from his troubled home life to his flight from Youngstown to study music at Oberlin College & Conservatory; from his quest to reach Carnegie Hall to his first encounter with the man who would change his life.

"I'll tell you what," Clemmons said, "when I first met Fred Rogers, I thought that man was hitting on me."

Let's Be Together Today

- Caleb Kenna

- François Clemmons

Once upon a time, a long time ago, a young Clemmons sang a Good Friday service at a Presbyterian church in a big city called Pittsburgh. It was an unusual program because Clemmons selected several spirituals to be sung alongside the usual scripture readings. Clemmons loved singing spirituals, and no one sang them quite like he did, especially not at churches in Pittsburgh.

"It was a magic time," Clemmons said. "When you're charismatic, something just happens. I open it up, knock at the door of heaven and say, 'What y'all want?' Everybody in the church stayed when it was over."

That included Rogers, who wanted to meet the singer.

"I looked over there, and there was the most boring, plain man," Clemmons recalled, laughing. "He was so plain. He defined the word 'plain.'"

Rogers also defined the word "sincere."

The two men stood and talked for a long while, Rogers asking Clemmons about his program of spirituals. "His sincerity touched me," Clemmons said. "He was sincere and humble, asking serious, interesting questions."

At the end of their conversation, Rogers invited Clemmons to lunch.

"My mind went Brrrt, brrrt!," Clemmons said. "Is he trying to go to bed with me?"

He wasn't. Rogers simply took an interest in a talented performer.

(Clemmons is often asked about Rogers' sexuality and has maintained for decades that the man was straight. "He was soft," he told Vanity Fair in 2018, explaining why so many people thought Rogers might be gay.)

That day at a church in Pittsburgh marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship, not to mention one that would permanently change television.

At the time, Clemmons was studying for his master's degree in fine arts at Carnegie Mellon University, working his way toward becoming a professional opera singer. Young, single and driven, he had no interest in television, let alone children's TV.

"I thought I was on my way to Lincoln Center," Clemmons said. "The Metropolitan Opera was calling me and, child, I was going to answer. But life had a different journey for me."

After their lunch meeting, Rogers invited Clemmons to his show's studio at WQED in Pittsburgh. He showed him the living room set, the trolley, the Neighborhood of Make-Believe.

"I thought, Why is he showing me this stuff? This is kiddie shit,'" Clemmons said. "Then he showed me the puppets. A grown man playing with puppets? You've got to be kidding me. I thought that man was crazy."

Clemmons left the studio that day thinking he'd never come back. But Rogers had different ideas.

After some time, Rogers began leaving phone messages for Clemmons. When Clemmons finally returned his calls, Rogers invited him to a taping.

"Watching them film, I got a different feel for him, for his seriousness," Clemmons said. "I still didn't like the puppets, but I saw that he had purpose, and I liked that about him."

Rogers asked Clemmons to sing on his show as a guest. Soon after, he invited Clemmons to join the show as a regular.

"I told him I would be very happy to be on his program as long as it didn't interfere with my singing career," Clemmons said. Later, he added, Rogers told him, "That was the moment I loved you. Because I knew you couldn't be that dumb. And I knew you were not going to kiss my ass."

"I was the dumbest country black boy in Pennsylvania in 1968," Clemmons said. "I could not have been dumber. He was handing me this treasure. It was just meant for me.

"So many good things happened to me because of that program," Clemmons continued, "and I didn't have to sleep with anybody."

Be Brave, Be Strong

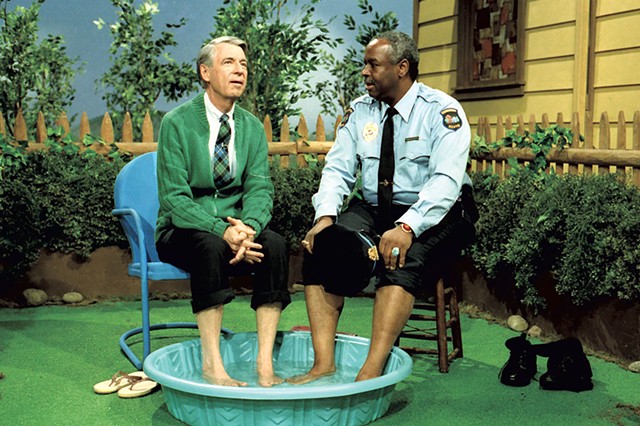

- Courtesy Of Focus Features/john Beale

- Mister Rogers with Officer Clemmons on the May 9, 1969, episode of "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood"

Officer Clemmons was a regular on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" for most of the late 1960s and '70s. He was always a popular character, but on May 9, 1969, he became an iconic one.

Though most of America had been legally desegregated by then, racial tensions still ran high. That was especially true at community pools around the country; in some places, black people were forcibly prevented from swimming. So, in episode 1065, Rogers and Clemmons staged a quiet but radical act of protest.

Rogers invited Clemmons to share a small wading pool with him to cool his bare feet. The image of the two men sitting together around a child's plastic pool is perhaps the show's most enduring; it's on the cover of Clemmons' book.

"Fred was for everyone," Clemmons said. "Black, white, Latino, Chinese, it didn't matter. His message was to humanity, not to color."

Clemmons was key to Rogers' reaching nonwhite audiences — and to helping change perceptions among white ones. That gentle message of inclusion is one that Clemmons feels A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood missed a golden opportunity to spread. Officer Clemmons is one of the only regular characters who didn't appear in the movie, perhaps because he doesn't show up in Junod's article. The Esquire writer reported his story in 1998, five years after Clemmons left the show.

Regardless of the movie's source material (which the screenplay semi-fictionalized), "You're not just telling the story of a reporter and Fred Rogers," Clemmons said. "You have the additional responsibility of being a social and cultural commentator on the highest level.

"Not having Officer Clemmons, a black policeman who went through all kinds of hell in that role, is avoiding black people," he continued. "Fred always comes off as a white savior. But he's not. He's for everybody, and the movie doesn't help people understand the totality of Fred Rogers."

Everything you've heard about Rogers being kind, gentle, loyal and full of empathy is true — and perhaps actually undersold, according to Clemmons. Rogers was protective of the neighborhood he'd built and what it stood for. In his quiet way, he championed kindness and racial equality on screen. He famously took on Congress when the government threatened to defund public broadcasting. (That hearing took place on May 1, 1969, shortly before the pool episode.) But when it came to Clemmons' sexual preference, Rogers drew a line.

Clemmons maintains that Rogers, a devout Christian, was privately supportive of him and never judged him. Still, he wouldn't allow Clemmons to wear an earring on screen lest the "wrong people" draw conclusions. When Clemmons was spotted with a friend at a gay bar in downtown Pittsburgh, he recalled, Rogers called a meeting to tell him he couldn't be publicly out of the closet and be on the show.

According to Clemmons, Rogers felt his open sexuality might bring controversy that could damage the show — and put Clemmons in danger. It was one thing to have a black policeman in the cast. But a black gay policeman? Clemmons conceded that parts of America probably weren't ready for that, at least not on a children's TV show.

That left him with an impossible choice. Officer Clemmons had commandeered cultural significance and had a national platform to change the world for the better.

"It can't be overstated how important it was for black kids to see black people on TV, especially at that time," Clemmons said.

But to keep that platform, Clemmons had to hide his true self. Worse, for a time he even tried to pretend to be someone else.

At the suggestion of both Rogers and Clemmons' own church, Clemmons married a woman and attempted to live like a straight, red-blooded American man. As he writes in his book, that meant washing his car by hand, taking trips to the hardware store on weekends, drinking beer at the neighborhood pub and (half-heartedly, he notes) ogling women, among other supposed manly pursuits.

As anyone who knows Diva Man today might guess, the experiment didn't take. His marriage was short-lived and, as Clemmons put it, "a complete disaster."

Though brief, the experience made a lasting impact. Clemmons believes that, coupled with his mother's condemnation of his sexuality when he was younger, being forced to hide it prevented him from learning how to have a real, significant romantic relationship with another man, which he says he's never had.

"I made a sacrifice because I knew the importance of what I was doing," Clemmons said. "And I've carried that burden every day since."

As Clemmons' music career picked up in the 1980s, he appeared less frequently on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." By 1997, he was working at Middlebury College full time as the Alexander Twilight Artist-in-Residence and held an honorary doctorate from the school. But he carried Rogers with him always, and still does.

Clemmons often refers to Rogers as a father figure. That's a role he himself has embraced for his legion — some 700 to 800, by his count — of "cosmic children."

Sometimes I Wonder If I'm a Mistake

Once upon a time, a young man named Daniel Houghton was having trouble. He was a 20-year-old student at Middlebury College who struggled, he said, "to build an identity after leaving home."

Though Daniel didn't quite understand it at the time, the problem was that he'd given up on the things he'd loved in high school, the things that gave him a sense of direction and self.

Before college, Daniel loved making movies with his friends. He spent most of his senior year of high school working on one. But one day, after months of filming, the footage was destroyed in a car crash.

"This year's worth of project just vanished in one night," Daniel said. "I felt responsible and sad."

Because he was only a teenager, Daniel didn't know how to handle those sad feelings. When he got to college, he was depressed and started doing other things, because "something about making movies was too hard to go back to," he said. "I was not myself for a period of years."

Have you ever felt like you weren't yourself? That's a scary feeling, isn't it?

One day, Daniel met Mr. Clemmons through mutual friends. Mutual friends are people you like who know other people you might like. Mr. Clemmons liked Daniel and offered him a job filming a TV show he was making called "Studio 104." Daniel would get to make movies again.

Daniel accepted the job. But not long after, he dropped out of college. Daniel had dropped out of Middlebury several times, but he always came back. When he returned to school this time, he sought out Mr. Clemmons.

"I had the nerve to call him back up and ask for the job back," Daniel said. Mr. Clemmons agreed, and he and Daniel became very good friends.

"I found him a great mentor who was willing to hear my grievances as a young and lost 20-year-old," Daniel said. He started making movies again, too, on which Mr. Clemmons would offer him "friendly and kind and productive thoughts and notes," he recalled. "It was really meaningful, because I was spiritually homeless at the time."

Daniel eventually graduated from Middlebury College. Do you know what he does now? He makes animated movies. Even better, he teaches other people to make animated movies, too.

Daniel runs the Animation Studio at Middlebury College. After he got the job, almost 10 years ago, he lived with Mr. Clemmons for about two years. He and Mr. Clemmons were roommates. Isn't that fun?

Daniel thinks Mr. Clemmons is a big reason why he was able to follow his dream of making movies. A great many of Mr. Clemmons' cosmic children feel that way about him — that he helped them discover, or rediscover, their true selves.

"I met him as a scared and lost kid and grew to respect him as a mentor," Daniel said. "Then I got to see him dressed head to toe in pink satin at my wedding. Then I got to see him working in a place that I had come to work at. Then I got to see him as I had kids.

"The relationship has been long enough now that it's become complex in a way that is kind of beautiful and meaningful," Daniel said. "He's not simply a nice guy who helped me out in college. He's become part of the family."

There Are Many Ways to Say I Love You

Clemmons isn't the only "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" cast member to receive an honorary degree from Middlebury College. In 2001, just two years before he died, Fred Rogers gave the commencement address at the school's graduation.

That morning, it was misty and threatening rain at the outdoor ceremony. When Rogers stepped to the lectern, he invited the assembly to sing a familiar tune.

As the strains of "A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood" filled the air, "I kid you not, the skies parted," recalled John McCardell, who was then president of the college.

McCardell was instrumental in bringing Clemmons to Middlebury. (The two struck up a friendship following several Harlem Spiritual Ensemble concerts at the college.) And he has a Rogers anecdote of his own.

On the evening of that graduation, as McCardell's family ate dinner, the phone rang. McCardell's son Jamie, who was 11 or 12 at the time, answered. It was Rogers. They chatted briefly, and Rogers thanked Jamie for having him in Middlebury. When Jamie asked if Rogers wanted to speak to his parents, Rogers said no; he'd called specifically to talk to Jamie.

To McCardell, who left Middlebury in 2004 and is currently the vice-chancellor and president of Sewanee: The University of the South in Tennessee, that phone call encapsulates what made Rogers special — and, by extension, what makes Clemmons special.

"He's able to speak in a language and with a tone that children understand and yet is not patronizing or condescending," McCardell said of Clemmons. "He's able to relate to them in a way that I think accounts for his success and Fred Rogers' success.

"So much of that either rubbed off on François or was so innate to François that he and Fred Rogers were kindred spirits," he continued.

Lately, Clemmons has been encouraging another man who shares a kind of spiritual kinship with Rogers: Chris Dorman. Dorman is the host of "Mister Chris and Friends," a Vermont PBS children's TV show whose relaxed pacing and gentle tone owes a great deal to "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." (Disclosure: The author's brother, Tyler Bolles, plays bass guitar in the Mister Chris and Friends Band and composed the show's score.)

Throughout 2019, Clemmons served as something of a spiritual adviser to Dorman. He appeared on the show's Season 2 finale in November, and he'll sing on an album by the Mister Chris and Friends Band later this year.

Dorman explained that while Clemmons has offered some advice on the show from his time with Rogers, his most profound lessons have been more philosophical in nature.

"He's taught me how to go about living your dreams," Dorman explained. "He said it's always important to advocate for your dreams, because no one else is going to tell the story like you'll tell the story."

That advice undoubtedly rings true with Clemmons' cosmic children.

Toward the end of his memoir, Clemmons recounts more of that 2001 graduation ceremony. At the close of his speech, Rogers thanked and praised Clemmons by name, both for his work on the TV show and his contributions to the Middlebury community and the world at large.

He then played a song over the loudspeaker that Officer Clemmons once sang on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." It's a song whose message Clemmons has been singing, in one way or another, to his cosmic children and anyone else with the good sense to hear it, his whole adult life. It starts like this:

There are many ways to say I love you.

There are many ways to say I care about you.

Many ways, many ways, many ways to say

I love you.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.