- Luke Eastman

The press is "the enemy of the American people"?

Federalist authorities made much the same claim when they arrested my great-great-great-great-grandfather, Anthony Haswell, for criticizing a thin-skinned American president in Vermont's first newspaper.

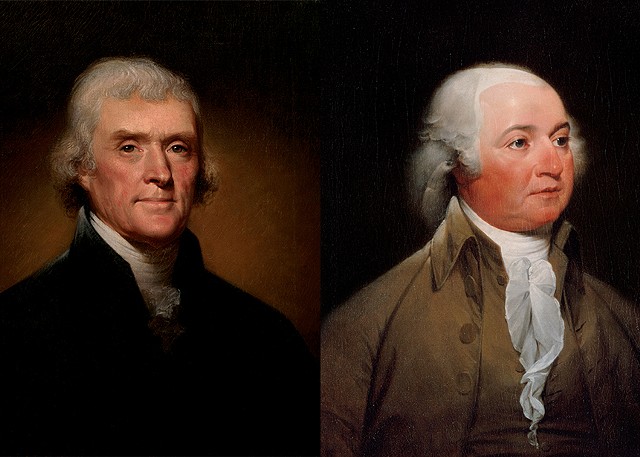

The year was 1799, and the new nation was in the darkest days of what then-vice president Thomas Jefferson called "the reign of witches." After narrowly defeating Jefferson in the first contested presidential election, John Adams and his fellow Federalists had exploited fears of a war with France to crack down on the immigrants and journalists they saw as sympathetic to the Democratic-Republican Party.

Congress soon passed the Alien Enemies Act, which granted Adams the power to detain and deport, without evidence or trial, any noncitizen he deemed a security threat. Then it approved the Sedition Act, which prohibited the publication of "any false, scandalous, and malicious writing" about the government, Congress or the president.

On a cold and rainy October morning, two deputy federal marshals came for my ancestor at his Bennington home. At first, they would not tell the 43-year-old publisher of the Vermont Gazette what crime he had committed — only that he was due in court the next morning in Rutland.

The marshals waited outside his abode, Haswell wrote years later, silent "as the midnight police officers of the French Bastile, the secret messengers of the Spanish Inquisition, or the Mutes of the Turkish bowstring for strangling."

Haswell, who was sick with a cold, mounted his horse to ride with his captors 50 miles over wet and muddy roads. When they arrived in Rutland at 1 a.m., the notorious federal marshal Jabez Fitch threw him in a dirty jail cell to await his arraignment.

Later that day, October 9, 1799, U.S. attorney Charles Marsh charged Haswell with two counts of printing "certain false malicious wicked and seditious libel" in the Gazette. The Bennington publisher had become one of 25 Americans arrested under the Sedition Act for criticizing the Adams administration.

The episode marked the first serious challenge to the First Amendment, which guarantees a free press — but it was hardly the last. As University of Chicago Law School professor Geoffrey Stone wrote in Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime: From the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism, the federal government "has attempted to punish individuals for criticizing government officials or policies" six times in American history. Each time, the nation was at war — or on the brink of it.

In an interview last week, Stone said he worried the U.S. may soon face another such test.

"I think it's important for people to remember that we are capable of doing things far worse than we think we are," he said. "So we should not be complacent."

Bennington Museum librarian Tyler Resch agrees. Following the 2001 passage of the USA Patriot Act, Resch set about researching the local publisher who had tested the limits of the First Amendment two centuries earlier.

"The Haswell story can be seen as the first chapter in a continuing saga of this nation's wrestling with the dichotomy of some very enlightened and venerable civil liberties versus recurring conservative curtailments of those liberties," he wrote in an address to the Vermont Humanities Council. "There always seem to be in our midst some duplicitous politicians and crafty bureaucrats who devise legal and extra-legal ways to subvert the First Amendment."

Reached last week at his North Bennington home, Resch said he saw "great parallels" between Adams' and President Donald Trump's disdain for immigrants and the press.

"I think there are great lessons to be learned here," he said. "Donald Trump would just love the Alien and Sedition acts."

The Spitting Lyon

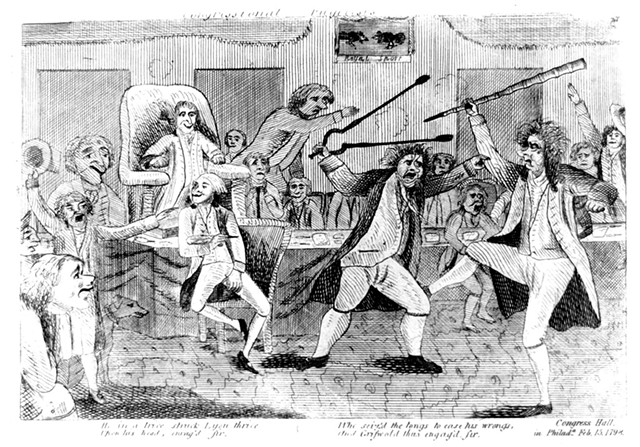

- Contemporary cartoon of congressman Matthew Lyon (left) fighting congressman Roger Griswold

U.S. congressman Matthew Lyon of Vermont, an Irish-born Democratic-Republican, was never one to shy from a fight.

Two years before Haswell's arrest, Lyon responded to an insult on the floor of the U.S. House by spitting in the face of congressman Roger Griswold, a Connecticut Federalist. Griswold escalated the matter by beating Lyon with his cane until the Vermonter's face was bloodied.

It was, perhaps, a sign of the times. Despite George Washington's admonition against the establishment of political parties, tensions were high between Adams' big-government Federalists, who represented the moneyed interests, and Jefferson's states'-rights-supporting Democratic-Republicans, a more populist group.

"Men who have been intimate all their lives cross the streets to avoid meeting, and turn their heads another way, lest they should be obliged to touch their hat," Jefferson wrote that year of the partisan divisions.

A diplomatic row with France, known as the XYZ Affair, only deepened the divide. Fearful of French aggression, the Federalists sought to root out the radical influence it saw in recent immigrants, the press and the Democratic-Republican Party. As Adams put it in a letter to Vermont Federalists in June 1798, "the exertions of dangerous and restless men" would mislead the public and "sink the glory of our country and prostrate her liberties at the feet of France."

While the Alien Enemies Act was ostensibly aimed at those involved in "treasonable or secret machinations against the government," it conveniently targeted immigrants — chiefly French, Irish and German — who largely voted for the Democratic-Republicans.

Similarly, the Federalists seemed to have in mind the opposition press when they approved the Sedition Act in July 1798. Democratic-Republican publishers, said Adams, went to "all lengths of profligacy, falsehood and malignity in defaming our government." The dishonest media's goal, added Federalist congressman "Long John" Allen of Connecticut, was to "ruin the Government by publishing the most shameless falsehoods against the Representatives of the people."

Democratic-Republicans argued that the Sedition Act was a clear violation of the First Amendment, but as Stone wrote in Perilous Times, even the framers "had no common understanding of [the] 'true' meaning" of a free press.

"It was an aspiration, to be given meaning over time," he wrote.

Lyon didn't wait long to test the Federalists' determination to enforce the Sedition Act. Upon returning to Vermont, the intemperate congressman sent a letter to the editor of Spooner's Vermont Journal, a Federalist rag based in Windsor, accusing Adams of a "continual grasp for power" and "an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation or selfish avarice."

On October 3, 1798, the same Rutland court that one year later would condemn Haswell indicted the congressman under the Sedition Act. Justice William Paterson of the U.S. Supreme Court, then presiding over the district court, sentenced Lyon to four months in jail and a fine of $1,000, plus court costs. Fitch, the federal marshal, dragged him away to a cold and squalid Vergennes jail.

It wasn't all bad for Lyon. Though he had lost three of his four previous bids for Congress, his trial and jailing made him a martyr — and he easily won reelection from his prison cell, defeating his Federalist opponent by a 2-to-1 margin.

Upon his release from jail in February 1799, Lyon set off for Congress in Philadelphia and was celebrated along the way. According to Haswell biographer John Spargo, the congressman "found an immense gathering of citizens awaiting him" in Bennington, "and right royally did they receive him."

"I heartily congratulate you on your escape from the fangs of merciless power," Haswell told Lyon, according to remarks published at the time.

Then the newspaperman led his fellow Vermonters in song:

Come take the glass and drink his health,

Who is a friend of Lyon,

First martyr under federal law

The junto dared to try on.

The Bard of Bennington

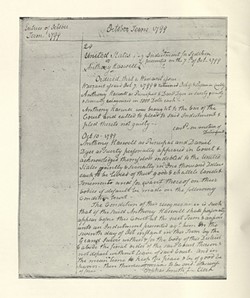

- Courtesy Of University Of Vermont Special Collections

Born in Portsmouth, England, in 1756, Haswell emigrated to Boston in his early teens with his older brother and their father, a ship's carpenter. The youngest Haswell first apprenticed with a potter but soon went to work for Isaiah Thomas, publisher of the revolutionary Massachusetts Spy.

As he recounted in an editorial years later, Haswell fell in with the Sons of Liberty and was present March 5, 1770, for the Boston Massacre, when the blood of patriots "stained the pavements of Kingstreet ... shed by the hands of British murderers."

After fighting in the Revolution, Haswell worked as a newspaper publisher in Worcester, Mass.; Hartford, Conn.; and Springfield, Mass., before accepting an offer from the government of the fledgling Vermont Republic. He would become its official state printer and postmaster general.

In the spring of 1783, Haswell loaded an ox cart with a handpress, type, his wife and two infants, and set out for Bennington. On June 5, he published the first edition of the Vermont Gazette, promising that "the freedom of the press [would] be inviolably preserved" on his watch.

Haswell did not have an easy go of it: Paper was scarce, a business partner bailed on him, circulation was limited and advertising rates were low. For decades, the publisher struggled to keep the Gazette afloat — and to stay out of debtors' prison. Attempts to found a Herald of Rutland and a Vermont Magazine both ended in failure.

But Haswell excelled at aggravating the Federalists. A month after Adams signed the Sedition Act, the newspaperman pointedly published its text along with Articles VII and VIII of the Constitution, which prescribe — and limit — the powers of Congress. In September he wrote that he had been "threatened with prosecution under the sedition law; with tarring and feathering, pulling down the house, etc." But, he declared, "their threats are void of terror." He promised his readers he would "conscientiously keep [his] post."

Days after Lyon's arrest in October 1778, Haswell felt compelled to announce in his paper that he was "attached to no party, but warmly engaged in the cause of liberty; an enemy to lawless power, and foreign and domestic tyranny, but a sworn friend to lawful authority and the federal constitution." He pledged to provide "impartial and true statements, to scorn the threats or grip of power, and detect the aim of despots when within the compass of his abilities."

In the end, it was not Haswell's own words that sent him to the slammer. In January 1779, a month before Lyon's prison sentence expired, the Bennington newspaperman published an advertisement for a lottery designed to pay the congressman's fine.

Lyon, the ad read, was "holden by the oppressive hand of usurped power, in a loathsome prison," where the "hard hearted savage" Jabez Fitch "can satiate his barbarism on the misery of his victims."

- Courtesy Of University Of Vermont Special Collections

- Bail bond issued after Anthony Haswell's October 1799 arrest.

After Fitch's deputies arrested him in October 1799, Haswell learned that he had been indicted for publishing the advertisement, though it had been written and paid for by Elias Buell and Lyon's son, James. (Neither man was prosecuted.) Haswell faced a second count for reprinting an article from the Aurora of Philadelphia questioning the loyalty of Adams administration appointees. Released on $2,000 bail, he spent the following months preparing for trial, in part by seeking evidence that the statements he had published, though not his own, were true.

As he set out for Windsor on April 29, 1800, to stand trial, Haswell documented his predicament in five stanzas of verse, reading, in part:

And if truth is a libel — Alas! and alas!

May the spirit of seventy-five,

Again be enkindled — A toast — let it pass!

For who would his freedom survive.

Like Lyon, Haswell never stood a chance at trial. The jury was stacked with denizens of the Federalist strongholds of Brattleborough, Putney and Westminster. And the judge, Justice Patterson, had little interest in Haswell's defense: that he had not written the words in question and that there was nothing false about them.

The passage he had cribbed from the Aurora had accused Adams of allowing into his administration Tories "who had fought against our independence, who had shared in the desolation of our towns, the Abuse of our wives, sisters and Daughters."

Secretary of war James McHenry had publicly admitted appointing Tories to the armed forces, but that wasn't enough for Patterson. To prove that the passage was not seditious libel, the judge said, Haswell must "identify the man holding commission, from whose hand the incendiary torch was wrested; who personally violated your females; or who personally discharged the murderous gun, that killed a citizen of America, or the proof is irrelevant to the point."

The jury quickly found Haswell guilty on both counts, and the judge sentenced him to two months in prison and a fine of $200.

"Of the trial it is hardly too much to say that a greater travesty upon justice has rarely, if ever, taken place in a court of law in the State of Vermont," Spargo wrote in his 1925 biography, Anthony Haswell: Printer-Patriot-Ballader. "Haswell stood that day before a political inquisition rather than a judicial tribunal."

But Fitch, the "hard hearted savage" the publisher had maligned in print, took mercy on Haswell. After holding his prisoner in Rutland for a day or two — far from his family and his newspaper — Fitch assented to Haswell's request to be lodged in a Bennington jail. The marshal brought him there after dark on May 13, hoping to avoid a scene, but word quickly spread of Haswell's return.

"Soon a small crowd of men gathered outside the prison and the keeper began to feel that trouble was brewing, when, to his great relief, the crowd began to sing one of Haswell's patriotic songs, which was followed by loud huzzas and other songs," Spargo wrote. "It was a humble tribute by humble folk to a neighbor and friend."

The tribute continued two months later, when the people of Bennington postponed their Independence Day celebration by five days so that Haswell could take part in it. On July 9, 1800, the publisher emerged from prison to a crowd of some 2,000 locals. The band fired up "Yankee Doodle," and the publisher marched through the streets at the head of a parade.

A 'Dishonest Press'

- Courtesy of the White House Historical Association

- Official Presidential portraits of Thomans Jefferson, by Rembrandt Peale, 1800 (left) and John Adams, by John Trumbull, circa 1792

So are we tumbling toward a second "reign of witches," with an abusive executive infringing on our civil liberties to punish his political foes?

While Trump's immigration executive orders indeed bear a resemblance to the Alien Enemies Act, he has yet to propose legislation curtailing the freedom of the press. Even if he did, he would face much greater obstacles than did Adams: namely, a firmly entrenched, popular understanding of the First Amendment and a Supreme Court inclined to protect it.

"Today the Sedition Act would be taken as unconstitutional, and that would hopefully be a check on the Trump administration," Stone says.

But the president has made clear that his understanding of and respect for the First Amendment is limited.

"We're going to open up libel laws, and we're going to have people sue you like you've never got sued before," he threatened the media at a rally in February 2016.

During Trump's rocky first months in office, he has continued to harangue the "dishonest press," accusing journalists of fabricating sources and refusing to report on terror attacks around the globe. He suggested on Twitter last month that the "FAKE NEWS media" was "the enemy of the American People." And he told Breitbart two weeks ago that the press was the "opposition party" and that the New York Times, specifically, was "so evil and so bad."

For Trump to succeed at cracking down on the First Amendment, Stone argues, he "would need to show there was a bit more of a crisis." That's how it has happened before — during the Civil War, both world wars, the Cold War and the Vietnam War.

The president has gone further than Adams in one respect: After U.S District Judge James Robart blocked one of his immigration orders last month, Trump appeared to lay the groundwork for blaming the judiciary — whose job it is to protect the First Amendment — should terrorists strike the country.

"If something happens blame him and the court system. People pouring in," Trump wrote on Twitter. "Bad!"

According to Stone, the most important lesson of the first attack on the First Amendment is that elections have consequences. As Adams prepared for a rematch with Jefferson in 1800, the president faced a backlash from his base for extending an olive branch to France. The Alien and Sedition acts, meanwhile, had alienated moderates and energized the opposition.

After Jefferson defeated Adams that year, the nation's third president allowed the Sedition Act to expire, and he pardoned Haswell, Lyon and the law's other victims.

"The reason we can tell the story we can tell today is because Jefferson won," Stone says. "If Jefferson lost, it would have been a different story."

Years after his pardon, Haswell made the same point in verse, as my great-great-great-great-grandfather was wont to do:

At length election came about,

And democrats were handy,

They plied their skill the land throughout,

Sing Yankee Doodle Dandy;

Then Thomas took the seat from John,

And dungeons lost their men, Sir,

Through Jefferson the grace was shewn,

Our press is free again, Sir!

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.