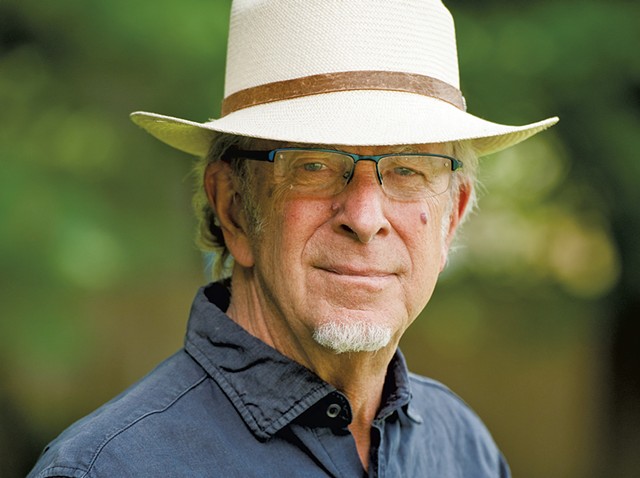

- Courtesy Of Jennifer Kiewit

- Christopher Shaw

Released in late summer 2020, Christopher Shaw's The Power Line escaped our attention until recently, but the book is an uncommon accomplishment that merits a belated review. Shaw, who lives in Bristol and has retired after 20 years of teaching creative writing at Middlebury College, preceded that career with a long stint in northern New York. His time on the other side of Lake Champlain, both as a guide and as editor of Adirondack Life, richly informs The Power Line.

The book declares itself to be a novel, and Shaw goes to some pains to support its status as fiction. He even prefaces his tale with a cautionary "Note to the Reader" that states:

The question of what constitutes truth in the printed word is of understandable concern to the careful reader, doubly so in these truth challenged times. It goes without saying that you should bring to your reading of this regional chronicle the same healthy skepticism you would bring to reading scripture, Shakespeare, or the New York Times.

Why does this matter? Because Shaw then proceeds utterly to confound his readers' grasp of the truthful and the apocryphal. The squirmy category of "historical fiction" will not do here, even though the author anchors his prose with real towns, rivers, lakes and peaks and sprinkles in real figures, from naturalist-turned-president Teddy Roosevelt to gangster Jack "Legs" Diamond.

The epistolary novel uses subtle but strategic point-of-view shifts to make the past feel present, just as a film narrator's voice-over might introduce a memory, only to fade out as viewers are immersed in the remembered experience.

Shaw's literary sleight of hand is particularly potent in the book's first section, which is ostensibly based on 1983 interviews with old-timer Alonzo "Lonnie" Monroe, recorded by would-be Adirondack historian Abel St. Martin.

Monroe is a riveting storyteller, and, as St. Martin puts it, "His story had too much inner consistency to be a total lie."

With growing enthusiasm and probable embellishment, Monroe recounts his escapades with his celebrated friend François Germaine, primarily in the years following World War I. The two endured combat in Europe and futile action against Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa before returning to the North Country. Like most self-sufficient locals of the Saranac region, they were skilled at hunting, fishing and navigating woods and waters, as well as guiding tourists who came to do the same for sport. Germaine, in addition, was an excellent fiddler in the French Canadian vein and a talented builder with a couple years of college behind him.

The men also really liked to drink — as, it seems, does just about everyone in this tale, with Prohibition perhaps serving as incentive. Monroe, Germaine and related characters soon find themselves working for Diamond, bootlegging liquor down from Canada. Monroe relates in vivid detail their escape from assassins in Montréal, with Germaine paddling the fearsome St. Lawrence River in the dead of a winter night.

This risky career builds to a shoot-out between the duo of Monroe and Germaine — renowned for his unerring aim — and a carload of gangsters from a rival operation. Along the way, both men develop relationships with women who show themselves to be more than flirtatious flappers.

These fictional events take place against a convincingly real backdrop. Monroe's tale spans the years that electrification arrived in the Adirondacks; he and Germaine work for real-life hotelier and developer Paul Smith (namesake of the college and town). Tuberculosis was real, too, and The Power Line deals with life and death in the local "san" communities. Not least, the book touches on the political and environmental machinations that led to the creation of the modern Adirondack Park Agency.

For all the fractious characters, rollicking anecdotes and colorful dialect, The Power Line is also steeped in the primal reality of geography and a near-reverential sense of place. Shaw's descriptions of nature can be incantatory. Readers unfamiliar with the region might want to keep a map handy, though; the naming of Adirondack towns and lakes sometimes comes at a dizzying pace.

Germaine disappears toward the end of the book's first section but reemerges in the second, which is based on the "discovered" diaries of fictional Rosalyn Orloff, a socialist and political theorist of the 1920s and '30s. Her well-connected circle of colleagues and friends, who visit her summer home at Lake Aurora, includes artists, philosophers, writers and even psychologist Carl Jung.

We'll not disclose what becomes of Germaine in part two, but suffice it to say there is a satisfying redemption. More cerebral in this section, the narrative is still studded with evocative observations such as this one:

Sheep laurel bloomed in patches of moss on the rock shore, along with the odd arbutus and clusters of bunchberries, partridge berries as they call them here, the stunted, wind-sculpted red pines and balsams like Japanese bonsai.

Shaw could have ended The Power Line with Orloff's final diary entry in 1938. But he goes on, in an afterword, to wrap up the biographies of the book's main characters — and continues to bend the parameters of fiction. If these characters' chapters are closed, Shaw promises that his writing about the Adirondacks is not.

From The Power Line

For Germaine and Monroe, the area had constituted an inheritance — a common birthright, even under Smith. They learned the ground by hearing it described over and over, even while in the womb, so when they got to a place for the first time, invited along to help and do chores at age ten or twelve, they already knew where they were and how it related to the whole. Part of that whole included Teddy and his exploits in the field and in politics. Later, to become one of the young hotel rowers and a registered guide meant ready cash, a name in the community, and a reputation among the swells (and their daughters), who might take a shine to you and render an important leg up in the world. You acquired standing, even without being Godfrey St. Germain's grandson or creating a distinctive style of log work all your own.

But your status undermined your equity in the place, your custody of it. No matter how acute your woodsmanship, or how deft your navigation of the minefields of class, you remained the help. Teddy, of course, always looked up to the woodsmen and guides, and used them as a model when picking his Rough Riders. This they knew implicitly.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.