- Courtesy

- Eric Rickstad

In Jewish folklore, Lilith was the first wife of Adam. The stories say God created them side by side, as equals. But Adam wanted a subservient wife. Unwilling to submit to her husband's authority, she was banished from the Garden of Eden.

The legendary Lilith has grown into an emblem of female liberation and male contempt. In southern Vermont author Eric Rickstad's seventh novel, a gripping thriller that bears her name, she becomes a national symbol for women no longer willing to put up with male violence.

Set in a small Michigan town, Lilith begins with the sort of violent episode that was once unthinkable yet has become commonplace. Elementary school teacher and single mother Elisabeth mentally prepares herself and thinks about her classroom for a monthly lockdown drill. She's come to doubt the efficacy of the shelter-in-place strategy now common in U.S. schools, and even her students poke holes in it.

If only she'd listened to her young son, Lydan, that morning. He told her that he had "an icky feeling" about going to school that day, but she shrugged it off, even though she'd rather have played hooky with him.

Elisabeth regrets that decision when an active shooter enters the school. Breaking school board-approved protocol, she flees with her class to the nearby town library, then returns to the massacre to search for Lydan. She finds him hiding in his classroom closet, bloodied and nearly unconscious. They barely escape with their lives.

The next few weeks are a blur. Elisabeth rarely leaves her son's hospital bed as he rests in an induced coma.

But she snaps out of her state of numb shock when she sees a televised interview with Iowa-based gun shop owner Max Akers. A national mouthpiece for the defense of the Second Amendment, he uses the tragedy at Elisabeth's school — and several subsequent ones — as a springboard to announce his candidacy for president. His genius idea for keeping public spaces safe: Give everyone a gun, especially teachers.

Akers' smugness enrages Elisabeth. When she discovers that the school district wants to punish her for defying the district's lockdown rules, her inner dumpster fire becomes an inferno.

At her hearing, Elisabeth's mind races. The attempt to suspend her seems like yet another instance of men punishing women for no good reason. She begins to see the school board blowhards, Akers and the shooter as part of the same problem, concluding that men have "a perceived right to violence."

"When trapped in a cage of facts that prove them wrong," she thinks, "they double down, triple down, quadruple down — instead of admitting fault, they lay siege to the facts and the messenger, retreat to defensive spite and self-righteous outrage."

If men perpetrate 99 percent of mass murders and sexual assaults, Elisabeth concludes, then men need to be punished — to be shown that their lust for guns and violence is unequivocally wrong, as is their insistence that more guns equal more safety. She decides the only way to make them understand is by committing her own act of violence, which she manages to secretly record. After she uploads the video to the internet under the pseudonym Lilith, she becomes a pop culture phenomenon, galvanizing both sides of the gun debate.

As pressure mounts to find the woman who started it all and bring her to justice, Elisabeth has to decide whether she can live with the anxiety of always looking over her shoulder. She's covered her tracks well, but even one missed fleck of dried blood could be her undoing.

Rickstad's prose, intimate and immediate in first-person present tense, regularly turns to a kind of poetry. His sentence structure collapses, and words float dreamily across the page. In the chaos of the novel's violent inciting incident, Elisabeth's thoughts devolve into clipped, dissociative ramblings:

Time fractures.

I am here but not here.

I am me but not me.

I have existed and never will exist.

I have existed for eternity.

This is real and not real.

It's an excellent method of encapsulating Elisabeth's wandering, unstable thoughts as she becomes a vessel for collective female rage.

Male violence is a running theme in Rickstad's work, whether he's writing serial killer thrillers (The Silent Girls and its sequels) or a gritty coming-of-age novel set in the Northeast Kingdom (his 2000 debut, Reap). Here, he expertly depicts a certain type of American man who, on the surface, is a family man, a pillar of the community, a "good guy" — but who, behind closed doors, makes jokes about murdered schoolkids and underage girls' genitalia.

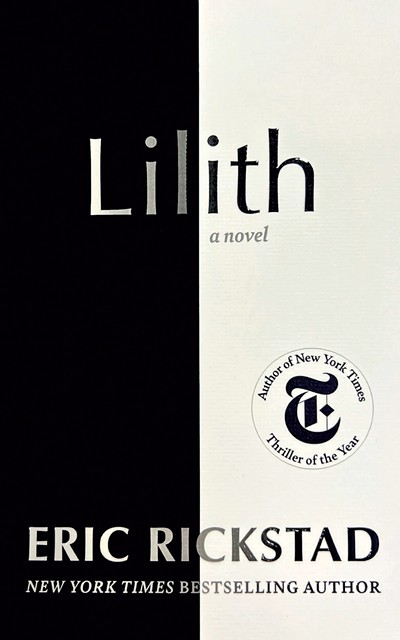

- Courtesy

- Lilith by Eric Rickstad, Blackstone Publishing, 245 pages. $26.99.

Rickstad only shows us the worst of these men, and the reader has little choice but to hate them as much as Elisabeth does. And he's not wrong in his underlying assertion that a deadly social disease infects many American men.

Through Elisabeth, the author conflates school shootings and other patriarchy-related woes. He reminds us that women (and everyone else) ought to be angry at men who try to manipulate, control and hurt women. But in the process, he skips over a crucial part of the mass shooting problem: mental health.

Elisabeth only fleetingly thinks of her school's massacre as an outcome of mental illness. She refers to the gunman as a "lunatic," an outdated and flattened explanation. Perhaps this is part of a pattern of deliberate character development. Against sound medical advice, Elisabeth refuses to take sedatives or antidepressants to ease her PTSD and anxiety. Mental health may be her blind spot. But since no character points this out or turns the conversation to the shooter's state of mind, the story lacks crucial nuance about what drives people — usually men — to commit mass shootings in the first place.

A few loose ends may also leave readers scratching their heads — for example, Lydan's convenient premonition about the shooting. But Rickstad offsets a few dangling threads with a wealth of details that recall real cases.

The children escaping to the library echoes the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Conn. The book's Michigan setting recalls that state's 2021 Oxford High School shooting, for which the perpetrator's parents were convicted of involuntary manslaughter in April. The message is clear: Rickstad could have set his story in many different places and still echoed reality.

An incredibly suspenseful and consuming novel overall, Lilith makes a memorable, bold statement about taking action instead of sending thoughts and prayers. Anyone even remotely tuned into social justice culture is likely to be fed up with "slacktivism." Much like the recent film Promising Young Woman, a story about a woman who takes her desire for vengeance against predatory men to an extreme, Lilith moves conversations about male power and female oppression further than the echo chambers of Instagram can ever hope to do.

From Lilith

Lydan's ribs rise and fall, shallow and weak, with the sound of a balloon leaking air. I don't dare put him down.

Carrying Lydan, I step toward the body of a man slumped in a chair at the teacher's desk. He's been shot in the head. Stan Taylor. He started his teaching career three weeks ago. Garrulous, creative, a teacher adored by students and teachers and parents alike. A natural. What was he, twenty-three years old?

"Close your eyes," I say to Lydan, even though his eyes are rolled so far to the back of his head that only the whites show. I don't know if he hears me or not. I rest him as gently as I can on a desk, beneath which lie two destroyed children.

The classroom doorknob rattles.

It knows someone is alive in here because I locked the door behind me.

I pick up a wooden chair and smash it against the window. The glass spiderwebs.

Poppoppop.

Wood splinters around the classroom door's knob.

I slam the chair against the window again. The glass shatters.

Pop pop. The doorknob blasts from the door.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.