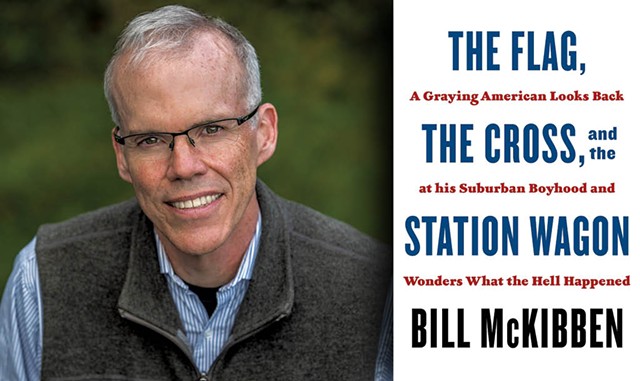

- Courtesy Of Nancie Battaglia

- Bill McKibben | The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened by Bill McKibben, Henry Holt, 240 pages. $27.99.

As a boy, Bill McKibben was exuberantly fascinated by the American Revolution. His family moved to the iconic town of Lexington, Mass., when he was 10. As a teenager, he served as a docent on the town's green, telling tourists about how colonial villagers confronted British soldiers in the first clash of the American War of Independence.

In his new book, The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened, McKibben offers a chapter on each of his title's resonant symbols. The book reads like a memoir but builds outward from anecdotes about his own evolving relationships with the flag, the cross and the station wagon to explore how patriotism, religion and consumerism in the United States since the 1960s have bequeathed us the society we now live in.

McKibben relates how, while still in high school, he began to work for the local newspaper, which would lead to a lifetime of reporting. Learning the observational and compositional skills of a writer compelled him to let go of an idealized rendering of historical events.

Not long after protests against the Vietnam War erupted in Lexington, the town held a watershed vote to prohibit multifamily (and more affordable) residences. These events forced the young reporter to think about the gap between his community's much-celebrated "revolutionary" origins (and self-congratulatory liberalism) and its increasing resistance to innovation and antipathy to newcomers, especially people of color and those of more modest means.

Annette Gordon-Reed's recent book On Juneteenth recounts experiences from her school days in Texas together with observations about the belated abolition of slavery in that state. Similarly, McKibben finds connections — and contradictions — between Lexington's role as the site of "the shot heard round the world" and the town's evolution into an enclave of privilege.

In these books, hybrids of autobiography and analysis, the authors' stories of their hometowns render hard-to-grasp societal changes more visible by viewing them through the lens of detailed personal memories.

Gordon-Reed distinguishes between history (which requires careful study of what she calls "change over time") and "myths and legends," which may be personally flattering and nationally glorifying but omit many truths about the past.

McKibben is interested in both history and myth, which are revealing in different ways. While describing his boyhood enthusiasm for those legendary, freedom-loving minutemen, he brings an adult's historical perspective to bear on specific ways in which America hasn't fulfilled its vaunted ideals for all citizens.

In the process and on the page, McKibben enacts an effort to understand the past from the wider perspective of now.

Author of 15 works of creative and topical nonfiction, two retrospective anthologies, and a novel, the Ripton resident has also contributed since his early twenties to the New Yorker and other publications. Early on, he cast off a journalist's postured detachment in favor of fervent advocacy. Outspoken for social justice and environmental action, he wrote the first book on climate change for general readers, The End of Nature, in 1989.

In 2007, McKibben cofounded the international environmental group 350.org, and in 2021, he cofounded Third Act, which aims to foster political activism among Americans ages 60 and over. He is currently the Schumann distinguished scholar in environmental studies at Middlebury College.

With disparities between wealth and poverty at an all-time high and participation in traditional civic and religious institutions at an all-time low, America is seen by many as a nation of extremes, including drastic differences in how government is perceived.

McKibben laments our culture's "hyper-individualism," a fanatical elevation of private over public in every realm of life, which "moved us as a nation from the expansive possibilities of the '60s to the cramped and grasping '80s idea that markets would solve all problems."

He has developed his own forms of patriotism (grounded in the egalitarian principles of the founders' writings, while not ignoring the flaws in their lives) and piety (based in what he considers to be a radically human Jesus, seeker of justice and humble decency). His many years of work with citizens, scientists, educators and entrepreneurs to avert catastrophic climate change have convinced him that a well-informed, thoughtful and determined citizenry can thrive while defending and improving democratic decision making.

The "Flag" and "Cross" chapters of this book are absorbing to read, though at times rather casual in manner. McKibben seems in some passages to be trying so hard to avoid sounding severe that he sounds garrulous, ingratiating.

Most memorable in the first half of the book may be his discussion of how Black families aspiring to move to suburbs were methodically excluded by zoning, lending practices, and disingenuous rules about "historic preservation" and "environmental conservation."

Also illuminating is McKibben's consideration of how Americans during the past 60 years have abandoned membership in churches, synagogues and mosques, a change that he says "dwarfs every other demographic shift in our country in my lifetime." During these decades, he himself has been a member of Presbyterian, Congregational and then Methodist churches.

The book gains greater verbal momentum and moral intensity when we come to the "Station Wagon" chapter, where McKibben probes deeper into the changes that led to our present-day climate collapse and economic devastation. Contemplating what he considers to be the pivotal year of 1970, he writes that by then "the car was the absolute unquestioned reality of our lives."

It took no time — a decade — for America to construct itself around the car. That was what the suburb was, a reflection in concrete and wood and brick of the logic of the automobile, designed for its dimensions, its turning radius.

Contemplating the rapid swing to car-centricity, McKibben notes that "More than three-quarters of Americans drove to work, and most of them drove by themselves. By 1970, there were more than 118 million cars and trucks on the American road — more than quadruple the number twenty years before."

Throughout this book, McKibben harnesses statistics that leap off the page. These have a very different impact from data in bureaucratic reports or a typical news bulletin, because he provides his documentation in combination with stories:

"Lexington's population was 1.3 percent African American in 2020, down from 1.5 percent in 2010, down from 3.1 percent in 2000. Boston's public schools, by 2020, were 75 percent Black and Hispanic."

"In 2000, Bangladeshis emitted 0.2 tons of carbon per person; Americans emitted 22 tons per person, or about a hundred times as much."

"If you're sixty, 82 percent of the world's fossil fuel emissions have occurred in your lifetime."

In the book's final section, McKibben muses on what might have been, if Americans had made different choices in the 1970s. Modern civil rights victories had led to surging hopes and new coalitions. The end of the war had freed up resources. Our energy systems could have been transformed by renewable technologies already viable at that time.

Then, turning to the present, he offers a challenge to older Americans, "the generations who have given us the troubled country we inhabit" — who now have the resources and time to give to a truly democratic movement of social change and who vote in large numbers:

I think the only way to make our heritage any better is to make our present and future better: if we change decisively in the direction of inclusion and fairness, then perhaps history — taking a very long view — will see something worth lauding in the promise that "all men are created equal," or in the Gospel injunction to love one's neighbor; perhaps if we install enough solar panels, the American science and engineering of the twentieth century (which birthed all those miraculous devices) will be remembered for more than making the comfortable more so.

From The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened

[I]n Lexington, I was confirmed into the United Church of Christ, the direct theological descendant of those Puritans, back through Reverend Clarke and Bishop Hancock. The UCC lists among its key "theological grandparents" Jonathan Edwards, often regarded as among America's greatest theologians, a stern figure remembered best for his famous sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." Edwards purchased several human beings — he traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, to buy the first, a fourteen-year-old girl named Venus, who had been kidnapped in Africa. Edwards, a frugal man, used the back of the bill of sale to write a sermon; in his will he described his slaves as "stock." As an adult I became a Methodist, again because that's what there was in the small and isolated rural town where I made my life. Methodism's British founder, John Wesley, was an opponent of slavery, and a brave one—he preached an antislavery sermon in Bristol, England's main slave-trading port, and indeed it caused a riot: "the terror and confusion were inexpressible; the people rushed upon each other with the utmost violence." But Methodism's first important American leader was a man named George Whitefield, who helped spark that first Great Awakening. Whitefield campaigned to allow slavery in Georgia, in order to maintain the plantation that supported an orphanage he had founded. He left fifty slaves in his will.

So: [religion was] poisoned at the source. Or: inextricably bound with American history, listing and lurching with the turns of that story, sometimes helping progress and sometimes holding it back.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.