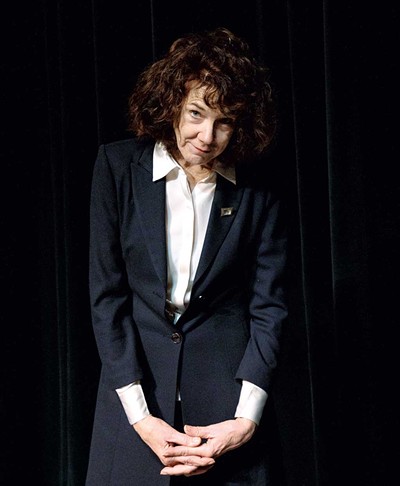

- Courtesy Of Libby Lewis

- Mary Ruefle

When Mary Ruefle of Bennington was chosen in 2019 as Vermont's ninth poet laureate, she followed the lead of many of her predecessors and devised a special project. Instead of vowing to give a reading at every library in the state, as Sydney Lea did, or coediting an anthology of Vermont poets, as Chard deNiord did, Ruefle pursued an even more old-fashioned aim. During her tenure, she has been mailing handwritten poems to Vermont residents, with a goal of delivering a thousand of these unexpected gifts.

In 2020, Ruefle told Seven Days that she was choosing her recipients from the names listed in telephone directories "using a proprietary dowsing method, a private game of conscious association and instinct." This combination of whimsy and earnest human solidarity is a reliable feature of Ruefle's own writings, which are both shrewd and generous.

Her new volume of prose poems is demurely entitled The Book. But the contents are bristling with surprises, as the poet orchestrates collisions between divergent topics and perspectives.

Ruefle's 22 previous volumes include Dunce, a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize that was also long-listed for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics' Circle Award; and Madness, Rack, and Honey: Collected Lectures, a finalist for the 2012 National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism. She has also published a comic book called Go Home and Go to Bed! and an illustrated, chapbook-length essay called On Imagination, now hard to find but delightful and worth tracking down.

Ruefle is also a visual artist who specializes in expressive "erasure," producing new pieces by erasing segments of existing work by other authors. Her erasures of 19th-century texts have been exhibited in galleries and published in the collection A Little White Shadow.

In The Book, Ruefle can be commonsensical and wily, mournful and comic, friendly and roguish — all within the same poem. Here's the entirety of "The Bark":

In these latest works, Ruefle embraces the long, international tradition of prose poetry. Some readers may find the term paradoxical. Isn't a poem by definition made of lines? Why would a writer forgo the audible power of musical measures in verse?

- Courtesy

- The Book by Mary Ruefle, Wave Books, 112 pages. $25.

The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics describes prose poems as a "controversially hybrid and (aesthetically and even politically) revolutionary genre." The entry observes that "with its oxymoronic title and its form based on contradiction, the prose poem is suitable to an extraordinary range of perception and expression." Tracing the older sources of prose poetry to biblical versets and folk and fairy tales and its modern origins to mid-19th-century French innovators such as Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud, the encyclopedia praises the form's "high patterning, rhythmic and figural repetition, sustained intensity, and compactness."

Ruefle has excelled in writing agile, syncopated free verse, but her prose poems are even more unusual. Her investigations in the genre have yielded a sound all her own. You hear in these new poems how poetic prose can absorb and parody the regular prose of daily life: articles, advertisements, letters to the editor, legal documents, business correspondence.

Ruefle is also terrific at incorporating dialogue. Here's the opening of "A Lesson in History," which has the impetus of an overheard outburst:

Throughout the book, Ruefle's narrator adopts various postures, sounding at times like a professor professing, a sketch comic spinning out scenarios, and a logician testing propositions about the nature of language and reality.

The plot and theme of these poems is thinking — thinking aloud. Ruefle believes, as she says in On Imagination, that reading is "a form of listening." Listen to the mind's voice in the opening to "The Color," where her vignette meanders and swerves, seeming to drift but then pouncing.

While Ruefle's subjects are often ordinary, her way of seeing — and of watching herself seeing — is anything but banal. Her point of view is steadily, insistently odd. The effect is to accentuate how improbable everyday existence can be.

At the center of The Book is a longer piece, "Dear Friends," a 22-page rumination on friendship with a recurring refrain: "I have a friend who..." Ruefle has a knack for reenergizing words, for instance the well-worn "love":

I have a friend who is not a person I could ever be, even if I tried, nor would I want to be, and I love being with her.

Many readers of this gentle, whip-smart and ingenious writer will "love being with her" — and will finish The Book feeling less alone. Strange as life is, we're in this together.

"The Translator"

Excerpt from The Book, © 2023 by Mary Ruefle. Used with permission of the author and Wave Books.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.