- Courtesy

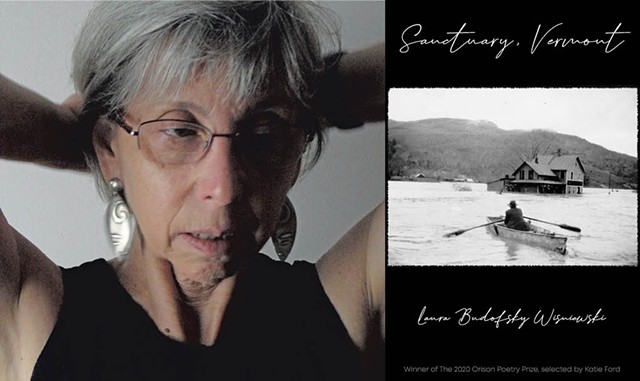

- Laura Budofsky Wisniewski | Sanctuary, Vermont by Laura Budofsky Wisniewski, Orison Books, 64 pages. $16.

Bob Brown walks 13 miles from Starksboro just to court Bea, a fiery resident of Sanctuary, Vt. "After I saw her beat the rugs in Spring / I'd toss my hat in first / before entering her kitchen," he says.

Good luck trying to find Sanctuary on a map: It exists solely in the poetic geography of Laura Budofsky Wisniewski. Winner of the 2019 Poetry International Prize and the 2020 Janet B. McCabe Poetry Prize, Wisniewski lives in Hinesburg, where she founded Beecher Hill Yoga. Sanctuary, Vermont, selected by author Katie Ford for the 2020 Orison Poetry Prize, is her first full-length book; Red Bird Chapbooks released her chapbook How to Prepare Bear in 2019.

The premise of Sanctuary, Vermont recalls the late David Budbill's Judevine. Like that locally revered rural poet, Wisniewski creates a fictional small Vermont town and populates it with a shifting cast of characters who tell us their stories in first person.

The book is divided into two sections, "Then" and "Now." The poetic history of Sanctuary begins in 450,000,000 B.C.E., when the Green Mountains are still forming. "Our Main Street runs the fault line like a scar," the poet tells us.

After this intriguing prologue, the book zooms ahead to the early 19th century, skipping over the region's indigenous history and bloody colonial period and landing squarely in what we might call mythical Vermont. That is, the Vermont of hardscrabble farmers living and letting live in God's pristine wilderness.

Readers who are eager to see literature deconstruct that whitewashed mythos, fret not. Wisniewski proceeds to do just that, presenting a collection of stories designed specifically to air all the Green Mountain State's dirty laundry.

Instead of affirming the neighborly, abolitionist vision of Vermont history taught in schools, Wisniewski populates her poems with voices speaking of economic subjugation, the forced sterilization of Abenakis, murdered Jewish peddlers and the years when "the Klan sprang up like mushrooms after rain." The effect is every bit as delightful as watching someone pop the balloons at a smug birthday party you didn't want to attend in the first place.

In "The War of the Rebellion. 1864," for example, instead of foregrounding the gallantry and sacrifice of Vermont men fighting to end slavery, the poet gives us the perspective of a desperately poor farmer's wife. "I begged my Frank to decline," she tells us. Her husband didn't enlist voluntarily, nor was he drafted; a wealthy citizen paid for Frank to fight in his place. Frank returns with one leg and "not right in his mind," and every market day, the wife tells us, the rich man who bought his way out of the war "smiles at me / and tips his hat."

The poems in "Then" proceed chronologically, leaping through history like a time machine. The townspeople recall the advent of electric fences on farms in a poem that also evokes barbed wire at the Dachau concentration camp. We see Cold War duck-and-cover lessons at school; the arrival of hippies and communes in the 1960s; veterans returning from Vietnam with PTSD; the Twin Towers falling; Tropical Storm Irene.

The "Now" section shows us parts of living in Vermont that usually go uncelebrated in poetry. The Tears & Fears Café is a Hopperesque diner that provides both a setting and a recurring motif throughout the book. We also find ourselves at an assisted-living facility, a wood shop, a deer hunt and a dairy farm where undocumented workers elude U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Wisniewski makes effective use of persona poems — written from someone else's perspective, in the form of a dramatic monologue — to broach difficult subjects and get her points across without railing from a soapbox. Occasionally, however, this strategy can backfire. At several points in the book, the author, who is white, writes from the perspective of Black, Indigenous, Québécois and Latino characters in ways that are well-meaning but don't quite work.

In "On my Marriage Prospects. 1888," for example, the poet speaks in the voice of a young Black woman: "I told my Daddy, No, I will not wed / a bag of bones. I do not care / if he is blacker than obsidian." While poems like these enrich the collection's array of voices, there's something that induces queasiness about white poets speaking on behalf of people of color and speculating about their struggle.

Sometimes, too, it's not clear who is voicing a poem. A few poems later, the speaker describes an attack by the Ku Klux Klan: "Their faces torch lit. / Among them, my own beau, Augustus Bannister." This poem seems to be depicting the terrorization of a Black family, but the notes in the back of the book indicate that the poem's speaker is actually of French Canadian descent and Catholic. This makes historical sense, since Catholics were one of the main targets of the KKK in Vermont, but there's nothing in the poem to indicate this beyond a French spelling of Maman.

These poems have a scavenger hunt aspect, requiring clarifying notes to establish their basic context, and there's something to be said for making readers do that work. If you weren't aware that Vermonters with certain backgrounds were forcibly sterilized well into the 1960s, for example, you will be frantically googling by page 13 of Sanctuary, Vermont.

Wisniewski seems to be aware of the discomfort and tension inherent in voicing others' experiences. Late in the book, "Her Story" presents the voice of a woman with a Black child, who warns the poet: "don't make / black and white photography / of the blood fear I feel / for my child's black body / in this tight white town. / Don't take my story / for your poetry."

However, these uncomfortable moments are few and don't overshadow a book that is otherwise thrilling to read. The author is most successful in confronting racism when she assumes the voice of a participant in it. "After Watching That Show on DNA and Race," for example, depicts a white married couple. The husband remarks, "If that was you / had that blood, I'd a never / married you." The wife, who narrates the poem, is both horrified by her husband's overt racism and too paralyzed by fear to do anything about it, even when he swerves his "size-matters Chevy" to frighten a Black mother and her baby in a parking lot.

We can't chalk up the wife's passivity to pure fear of her husband's reaction: She also simply doesn't care. Or rather, she cares only enough to feel "spun up inside myself, / like feathers in a dryer." What makes the poem so effective is how Wisniewski sneaks in a hint that this character may be on the verge of changing her life. Those feathers in the dryer have "floated down, / but not into the same old / what-do-I-know shoes."

There are two ways of dealing with uncomfortable history. We can sweep it all under the rug, or we can take the rugs outside into the sunshine and beat them. Sanctuary, Vermont is a rug beater of a book.

'The Great Flood. 1927'

Here at the bend,

Pond Brook has overrun its banks.

A man in a thin black tie and high black boots

slogs from shack to shack warning us to seek high ground.

And you with your fine wife, your clean sons, your house

of high calm from which you can look down

from Buckthorn Hill, you see us, the swamp

of our town, the roads tracked out like tears

to the farmlands, some by now deep under water,

livestock bawling, drowning in rain,

rain that kills the air, leaving only itself,

more and more of itself.

I can smell your skin on the good quilt, feel

your baby swim hard in me

as if there were a river

that led all the way to the sea.

Copyright 2022 by Laura Budofsky Wisniewski. Reprinted from Sanctuary, Vermont by permission of Orison Books, Inc. All rights reserved.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.