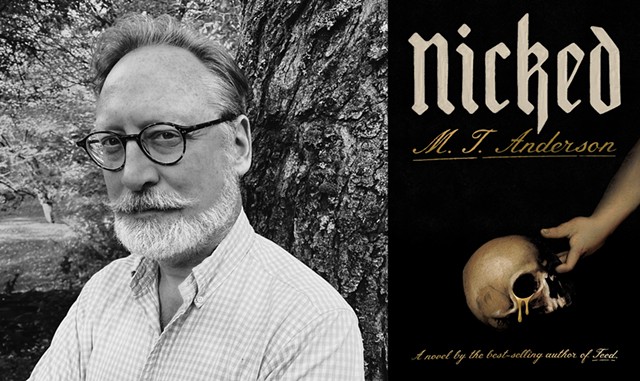

- Courtesy Of Erin Thompson

- M.T. Anderson | Nicked by M.T. Anderson, Pantheon Books, 220 pages. $28.

Readers who know St. Nicholas primarily as a figure of yuletide folklore may be surprised to see a book named for him released in July. But don't expect a Christmas tale from Nicked. The debut adult novel from Vermont author M.T. Anderson, a winner of the National Book Award for his young adult fiction, is not about the giving spirit. It's about the taking spirit — specifically how, in the year 1087, a crew of pious Christians ripped the corpse of St. Nicholas from its sarcophagus and rowed it back to ornament their city.

Nicked is a succinct historical heist story that evokes its setting in cinematic detail. We are in the multicultural turbulence of the fraying Byzantine Empire, itself built on the ruins of Rome. The thieves hail from Bari, a Byzantine city recently conquered by the Normans; the saint's remains reside across the Mediterranean in Myra, another Byzantine city that recently fell to the Turks.

The plot to steal St. Nick begins with a dream. In his slumber, a young monk named Nicephorus hears the saint insisting: "We must leave our nest." Having an "irritatingly pure and generous heart," Nicephorus interprets this as a call to minister to the plague-ridden populace. But the ambitious Abbot prefers to think that the sacred corpse is unhappy in its resting place. Soon the city's leaders hire a "saint hunter" named Tyun to nick Nick from his basilica.

Also described as a "Tartar pirate," Tyun is a grifter and medieval Indiana Jones in one, making his living off Christians whose eagerness to own a holy relic — that is, a lucrative tourist attraction — outweighs their faith. He's the polar opposite of Nicephorus, who can't even tell a lie. When the monk comes along on the expedition to give the theft legitimacy, these two opposites clash — and then attract, in ways both physical and spiritual.

A satirist in the George Saunders vein, Anderson uses his omniscient narrator to tell the story in shifting registers and sometimes even to break the fourth wall. He opens with a traditional poetic invocation to the saint that seems to situate the narrator in the 21st-century pandemic era:

In an age of sickness; in a time of rage; in an epoch when tyrants take their seats beneath the white domes of capitals—I call upon Saint Nicholas, gift giver, light bringer ... to tell us a tale to pass a winter night, so that when we rise in the morning, we may feel resolute in the new dawn.

A few sentences later, the narrator clarifies his own position vis-à-vis religion: "Though I am an unbeliever, I pray for faith." Undergirded by this earnest yearning to believe, Nicked takes a comically irreverent approach to Christian doctrine and historical facts alike.

In an afterword, Anderson explains: "I wanted to write a historical novel with the love of a good story, incidental detail, and willful inaccuracy demanded by the European Middle Ages themselves." Like much medieval and Renaissance literature, Nicked treats social realism as perfectly compatible with fantastical elements. So Tyun's sidekick, Reprobus, is a cynocephale — a man with a dog's head who speaks with the eloquence of a philosopher.

For the most part, Anderson adopts a wry, modern voice, sometimes deliberately juxtaposing the language of different eras. (One character replies to a long-winded question, "I guess yeah.") His dialogue can have the rhythm of cerebral sketch comedy:

"It is clear you are not Christians," said Nicephorus.

"We are the very soul of the Nazarene," said Reprobus, scratching his ear with his toes.

"More than half of the crew performs exercises five times a day facing Mecca."

While Nicked is funny, it isn't glib. Nicephorus is no buffoonish naïf but a full-fledged protagonist, learning from his worldly comrades even as he struggles with the ethics of their quest.

The novel's action scenes sometimes get a little overly cinematic in their blow-by-blow presentation. But most of Anderson's descriptions are marvels of compression, whether he's offering a vivid snapshot ("The sun fell aslant the channel and made helms blush the color of meat") or evoking the history of the Mediterranean landscape, studded with relics of fallen civilizations.

The author uses his setting to suggest that our sense of historical dread is far from unique; medieval folk, too, were obsessed with humanity's decline. In one memorable scene, Nicephorus and Tyun encounter an assemblage of heads salvaged from statues of various eras, stripped of glory and even significance: "Their eyes were holes or blank marble, glaucous, staring." An empty Roman amphitheater "felt like the last human building still standing at the end of time."

For the Barese and their Venetian rivals, to possess the bones of St. Nicholas (which reportedly ooze a healing ichor) is to transcend the march of time. Anderson has fun with the macabre lore surrounding saints' corpses, reminding us that the medieval attitude toward death and bodily functions was less decorous than our own. But he's also interested in the questions raised by that lore: Why do we still seek the essence of a deceased human being in their remains? Will we ever get past the Christian body-spirit duality? "We are all our own icon, our own avatar; an idol made in our shape," the narrator declares at one point, "haunted by a spirit longing to intervene in the calamities we witness."

That's heady stuff for a book featuring pratfalls and a dog-man. But we see similar tonal shifts in premodern classics such as Don Quixote, which the serious clowning of Nicked recalls.

There's a supreme irony in stealing the bones of a saint who was renowned for his generosity. Yet Anderson ultimately suggests that there are generous ways to take the world's bounty, as well as to give it. Nicephorus likes to repeat a saying he attributes to Alexander the Great: "When you are lost in the Land of Darkness, you must reach down and grab whatever objects you can find." Like Alexander, novelists are opportunists, turning the detritus of culture into their inspiration. To the gloomy mood of our current moment, Anderson brings an optimistic, rollicking tale lifted from the so-called Dark Ages, with imaginative additions. Foreign and familiar at once, this small book is a gift.

From Nicked

The treasure hunter was now prowling between the men, restless with the energy of expertise. "Everyone has a relic. Rome's burial grounds have been picked clean. The tombs of the Via Labicana, the Via Appia—they're barren now, gentlemen. Not a bone left. All the Roman saints are spoken for. Don't even ask. The monastery at Fulda has Sebastian and Cecilia sewn up. One pierced by arrows, the other burned to death and then beheaded while playing the hydraulic organ. Sure, Fulda only has a few shreds of Cecilia, but they also have Urban, Felicity, Felicissimus, and Emmerentina. They have Boniface, Cornelius, Callistus—who was buried right next to Cecilia—and Columbana." He spoke these names directly into the faces of the astonished merchants, smacking his hands together with each martyr. "Agapitus, Georgius, Eugenia, Maximus, Vincentius, and Emerita. I got them Columbana."

"Fulda is a most prosperous abbey," said the Archbishop, in a fever of longing.

"Constantinople," continued the saint hunter, "seat of great Byzantium, has the True Cross, of course—and also the two more disappointing crosses the thieves hung on. They have the body of the Prophet Daniel, the robe and girdle of the Virgin Mary, the hair of John the Forerunner, and the rod of Moses.

"Gentlemen, if you wish Bari to remain a great port city, you need a saint. And you need a saint with draw. I can get that for you."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.