- Matthew Thorsen

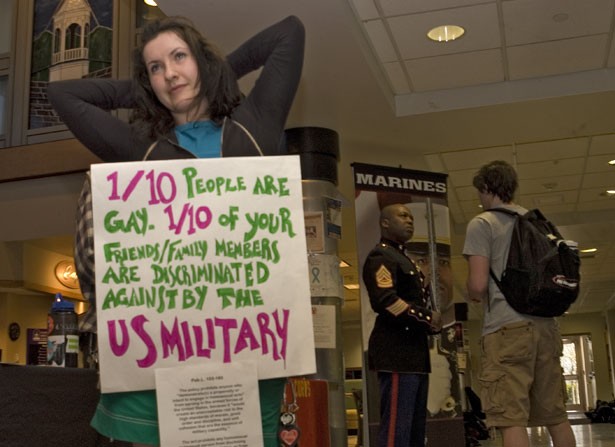

- Julia Blackeneiy-Hayward

Last Thursday, as Pope Benedict XVI addressed a few hundred Catholic educators in Washington, D.C., a Marine Corps recruiter in full dress uniform set up shop outside the St. Michael's College cafeteria.

For a couple of hours the recruiter, an officer named Will Morgan, shook hands and took down the names of a few interested students, then packed up his pamphlets and headed for the door. "Not bad," he said on his way out.

Meanwhile, a few feet away, a handful of St. Michael's students opposed to the Iraq war stood gathered around a cardboard sign: "Fight America's WARS," the sign read. "Sign up Here (straight folks only please)."

The contrast reveals a subtle tension: St. Michael's is one of the more progressive Catholic colleges in America, and antiwar students say most of their classmates, like the pope, oppose the war. Earlier this month, however, the college's Student Association rejected two pacifist resolutions.

The first, which proposed to ban military recruiters from campus, was axed by a margin of four to one. Since the college must host recruiters to qualify for federal funding, the anti-recruiter measure would have been non-binding.

The second resolution, "Students are [sic] Against the War," was also non-binding but had deeper implications. It called U.S.-sanctioned actions in Iraq "diametrically opposed" to the college's legacy of Edmundite pacifism. That resolution received a slight majority of yeas, but not enough for approval.

Student protestors offered their own views on why the antiwar resolutions didn't fly with elected reps. Julia Blackeney-Hayward, a junior political science major, said that Iraq isn't "relevant" to the college's affluent student body. On Thursday, she stood outside the cafeteria wearing a cardboard sign that criticized the military's policy on sexual orientation. Added senior Dillon Klepetar: "It's, like, a sin to talk about the war."

Klepetar introduced the controversial antiwar resolution to the Student Association back in March. That it sat for a month, he claimed, "is testament to how uncomfortable people are with taking a position."

At the peak of Thursday's lunch rush, Klepetar greeted David Landers, a psychology professor who has worked at St. Michael's for more than 20 years. After the resolutions failed to pass, Landers presented student leaders with casualty statistics at a meeting. Perhaps, he thought, their political apathy was a function of misinformation.

Fifteen years ago, students rallied behind Landers to challenge the armed services on their sexual-orientation policy. But now, he claimed, campus pacifist energy is so faint you'd be hardpressed to know there's a war on.

Not all of Landers' colleagues agree with that assessment. Toward the end of lunch, the antiwar crew greeted Laurie Gagne, director of the college's Edmundite Center for Peace and Justice. St. Michael's students are vocal advocates for humanitarian causes such as fighting HIV/AIDS, she said, and their lack of interest in the Iraq war is indicative of a national trend, not a campus-specific apathy.

But Catholics can and should take an antiwar stance, Gagne believes. The previous evening, she told an audience at St. Joseph Co-Cathedral in Burlington that the Iraq war can't be reconciled with "just war" theory. Unlike NATO's 1994 bombing of Kosovo, she said, Bush's pre-emptive 2003 invasion wasn't sanctioned by the United Nations.

Catholic doctrine holds that wars are only "just" if they are ethically sound in cause, intention and conduct, Gagne explained. Pope John Paul II, Benedict's predecessor, employed "just war" theory to oppose the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The same theory informs education on the St. Michael's campus. The college's Peace and Justice Studies minor, for example, pays homage to a 1983 pacifist manifesto, "The Challenge of Peace," which was penned by American Catholic bishops. On March 5, Gagne's Center for Peace and Justice sponsored a symposium entitled "Our War, Our Responsibility - Iraq at Five."

But on Thursday outside the cafeteria, Gagne admitted that the wording of the antiwar resolution - which asserts that American troops have been coerced into defending "empire" - was a bit strong for her taste. She disagrees with Matt Howard, Burlington chapter president of Iraq Veterans Against the War, who feels the resolution accurately reflects student opinion on the conflict. Howard, an outspoken Burlington activist, said he thinks the measure failed for lack of student leadership.

As Howard and Gagne lingered by the cardboard sign, Student Association President Alex Monahan grabbed a chair outside the cafeteria entrance. Monahan resists Howard's assertion that the Student Association didn't show enough leadership on the antiwar resolution. He speculates that the "majority" of St. Michael's students are against the war, but that the resolution's "empire" reference made student senators apprehensive to sign on.

Monahan, a senior accounting and business major from Massachusetts, has short hair and a well-trimmed beard. His older brother is a former Student Association president. "It's not our place to be there right now, and we need to get out," he said of Iraq.

That same day, Pentagon researchers were admitting that the war was, officially speaking, "a major debacle." A suicide bomber killed 50 at a funeral in eastern Iraq, and the U.S. military compound in Baghdad was strafed by rocket fire.

A few miles from the Pentagon, Pope Benedict told his audience that young people are losing sight of the connection between faith and civic life. It's up to Catholic educators to help reinforce that bond, he said. Only then will students see that knowledge "opens up the vast adventure of what they ought to do."

Alex Monahan admits that students today aren't as indignant about the Iraq war as their parents were about Vietnam. Perhaps for that reason, he's satisfied that the antiwar resolution prompted thoughtful discussion before it was struck down.

"Some feel that students live in this bubble, and I think that's true," he said. "But I also think they're more informed than people think. It might be that they're active in other things, but they do still care."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.