- Glenn Russell

- Robin Lloyd

As guests arrived at the Saturday afternoon party to celebrate the 80th birthday of Burlington activist, philanthropist and filmmaker Robin Lloyd, they were greeted at the garden gate by a wooden bowl filled with origami birds tied to strings. A handwritten sign suggested, "Hang a peace dove somewhere!"

This small, symbolic gesture was just one of several acts of solidarity that guests could undertake to honor Lloyd's milestone. At one end of the dinner buffet, a card table was lined with political pamphlets, including pledge cards to support one of Lloyd's latest projects: a forthcoming documentary by Massachusetts filmmaker Robbie Leppzer, titled Theater of the Possibilitarians: The Story of Bread & Puppet, which chronicles the Glover-based political theater troupe.

It was classic Lloyd: One doesn't visit her longtime home in Burlington's Hill Section and expect to be a passive observer. Once you enter her sphere of influence, everyone steps up and plays a part, no matter how small.

Doreen Kraft, executive director of Burlington City Arts, is one of Lloyd's oldest friends and collaborators; for more than a decade, the pair traveled together through Haiti and Central America making films. At the birthday party, Kraft shared the story of how, upon meeting Lloyd in Rochester, Vt., in the early '70s, Lloyd asked her to help give an arts presentation at a local church. Five months after the event, the two were still there, sewing banners with church members.

"That's one of the most magical things about Robin," Kraft said. "You go somewhere new, and you can end up ensconced in a new adventure."

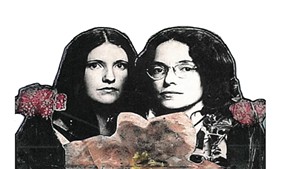

- Courtesy Of Jesse Lloyd Guma

- Doreen Kraft (left) and Robin Lloyd

For most of her adult life, Lloyd has thrown herself into all kinds of adventures, hanging her "peace doves" across the land. A documentary filmmaker could recount the history of the American social justice movement in the last half century just by tracing the many projects, organizations and grassroots campaigns in which she's been involved.

The fruits of Lloyd's labors were well represented at her party. The 60 or so guests, who sipped wine and nibbled appetizers in her garden, hailed from a cross-section of organizations that she either founded or has supported.

At one table sat a group of white-haired activists from the Women's International League of Peace and Freedom, a peace organization cofounded in 1915 by Lola Maverick Lloyd, Robin's paternal grandmother. Robin has long been a financial contributor, board member and activist for WILPF.

At another table sat Wendy Coe; she and Lloyd cofounded Burlington's Peace & Justice Center (initially the Burlington Peace Coalition) in 1979. Nearby was James Haslam, executive director of Rights & Democracy. Previously, he ran the Vermont Workers' Center and, before that, PJC's livable-wage campaign. Lloyd has contributed to all three.

Haslam noted that Lloyd was one of the first people he met when he joined Vermont's social justice movement in 1999. Since then, he's been impressed by the breadth of issues in which she's been involved, he said, "building an infrastructure" that's endured for decades.

"It's not hard to get wealthy people to invest in heartstring issues," Haslam added. "Robin invests in justice."

And her investments aren't just monetary. Time and again, Lloyd has proven her activist cred through nonviolent civil disobedience. In February 2012, as part of a campaign to close the Vermont Yankee nuclear power station in Vernon, Lloyd was one of nine women who donned death masks and were arrested for trespassing in the Brattleboro offices of the plant's owner, Entergy.

That wasn't her first, or most consequential, arrest. In November 2005, Lloyd was taken into custody outside the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation, formerly known as the U.S. Army School of the Americas, at Fort Benning, Ga. Since 1990, antiwar activists have held annual demonstrations there because the facility trains counterinsurgents, some of whom have been linked to human rights abuses. Lloyd served three months in a federal prison for her civil disobedience.

"She crossed the line," said Chris Lloyd, Robin's younger brother, referring to the now-ritualized process of how protesters get arrested at the annual marches. "She's always crossing the line."

At an age when most of her contemporaries have long since retired, Lloyd still seems to have an unquenchable thirst for the good fight. Admittedly, friends and family say, she's not as spry as she used to be. Lloyd now walks with a cane, speaks slowly and occasionally pauses mid-sentence to recall a name or detail from a protest, conference or project she worked on decades ago.

Nevertheless, those who know her assert that Lloyd's passion for her causes — opposition to war chief among them — burns as brightly as ever.

Ben Dangl is editor of Toward Freedom, the progressive international news journal founded in 1952 by William Bross Lloyd Jr., Robin's father. Dangl, who's worked for Robin since 2005, described her as "a visionary" who continually pushes the online magazine's freelance writers and board members to think and act as idealistically as she does.

"She's always off to another teach-in or march or demonstration," Dangl said. "It's incredible to see that level of energy sustained the whole time I've known her."

Journalist Greg Guma, Lloyd's onetime romantic partner and father to their son, Jesse, said that if Lloyd's political activism has waned in recent years, "I don't see any sign of it."

On June 27, the Vermont International Film Festival honors Lloyd with its 2018 VTIFF Community Champion Award, both for her own cinematic work and for supporting other local filmmakers for decades. The occasion allows Vermont's film community to celebrate one of its most generous and prolific patrons.

"Robin stands tall for her decades-long commitments to the arts and a potent and enduring progressive social vision," said filmmaker Jay Craven, of Kingdom County Productions in Barnet, in an email. "She has supported my work for nearly 40 years and has been a dear and appreciated friend through thick and thin."

Craven's partner and fellow filmmaker, Bess O'Brien, echoed that sentiment. She marveled at Lloyd's accessibility and willingness to support groundbreaking projects without expecting people to jump through the hoops of a laborious grant-application process.

"Filmmakers don't always have people who understand their work," O'Brien added, "but Robin totally gets it."

Lloyd's activism is often close to home, literally. Since the 1980s, she has routinely opened her house to refugees, asylum seekers and others in need of shelter — for days, weeks, even months. Garry Davis, the international peace activist who created the World Passport, was among her more famous houseguests.

At times, Lloyd has welcomed those shunned by others. In 2004, she hosted newly released parolee Steven Buelow. In August 1988, the then-14-year-old had raped and murdered his 7-year-old step-cousin, Crystal Sumner, in a Bristol cornfield.

"It was a terrible thing," Lloyd recalled of that horrific, high-profile crime, "but we just felt that he was an underaged kid who deserved a second chance, despite the sadness of the act he performed." He only stayed a short time — perhaps a few days to a week — and then moved out of state.

As a lifelong Quaker dedicated to compassion and nonviolence, Lloyd occasionally takes positions far removed from the political mainstream. As Burlington attorney, activist and longtime friend Sandy Baird pointed out, Lloyd was a vocal supporter of the rights of the Palestinian people years before that was an acceptable position to express publicly, even among fellow progressives.

But Lloyd has never shied away from alienating potential allies. In May 1999, she condemned then-Rep. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) for his support of NATO's bombing of Yugoslavia. "We had depended on you to speak truth to power in Washington," she told him before a crowded public forum in Montpelier.

Peter Clavelle, Burlington's seven-term Progressive mayor who hosts this week's VTIFF Community Champion Award event, once called Lloyd "the conscience of our community." But he admitted that she also could be "a pain in the butt sometimes."

Why? As Guma put it, Lloyd is a "true believer" who cleaves to positions, including unpopular ones, that she believes are moral and just. In May 2011, she and Baird called a press conference to condemn the assassination of al-Qaeda cofounder Osama bin Laden as "an act of murder" by the Obama administration. As Lloyd explained recently, "The rule of law either applies universally, or it doesn't."

She has even questioned whether it's morally defensible to kill Islamic State militants. In an op-ed piece published in the Burlington Free Press on April 16, 2017, Lloyd wrote: "Do they hate us, or do they simply want us to get out of their space? ... Perhaps some of them are simply poor farmers who have been given a good salary for the first time in their lives."

Critics might roll their eyes at Lloyd's idealism and seeming naïveté, but Baird sees Lloyd's principled stances not as weakness but as her greatest strength.

"Robin is consistently antiwar," Baird explained. For her, "there are no excuses."

If Lloyd has an Achilles' heel, Guma suggested, it's her unwillingness or inability to say no to people who need help.

Her son, Jesse Lloyd Guma, noted that his mother often pooh-poohs suggestions that she be more generous to herself when, say, she needs a new appliance.

"She'd rather give the money to the Haitian relief fund," he said. "She's always been that way."

Mavericks and Muckrakers

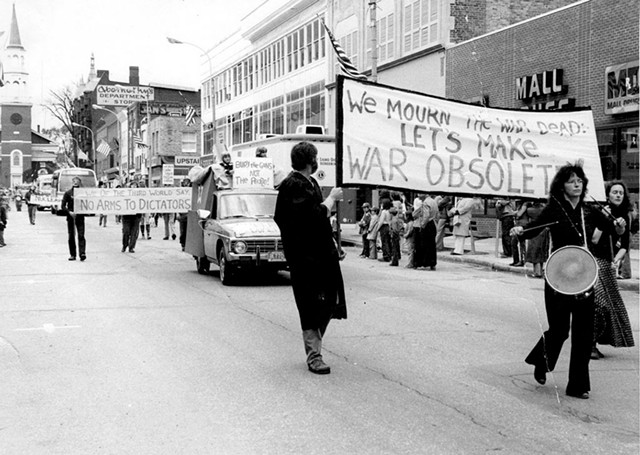

- Courtesy Of Greg Guma

- Robin Lloyd banging a drum on Burlington's Church Street with the Peace & Justice Center's Wendy Coe in the background, circa 1980

Lloyd's storied history began, as she told Seven Days in 2001, with the "anarchist cows." That's what she called the cattle that her paternal great-great-grandfather, Texas rancher Sam Maverick (1803-1870), refused to brand because he considered the practice inhumane. Through that small kindness, the San Antonio lawyer and land baron introduced the word "maverick" into the American lexicon — and the maverick identity into his bloodline.

In many respects, Lloyd has most closely followed in the footsteps of her paternal grandmother — Sam Maverick's granddaughter — Lola Maverick Lloyd (1875-1944). Lola's father was Henry Demarest Lloyd (1847-1903), the famed Chicago Tribune journalist and progressive. He was a muckraker long before president Teddy Roosevelt popularized that term, writing searing exposés about John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil.

Lola was a suffragist, pacifist, feminist and philanthropist. She cofounded the Women's International League of Peace and Freedom and the Woman's Peace Party in 1915, and was among dozens of women who risked the perilous crossing of the Atlantic Ocean that year in an attempt to stop World War I.

"She became convinced that war was a terrible violation of human rights and justice," Lloyd explained, "so she stuck with that for the rest of her life."

Lloyd herself grew up in the tony Chicago suburb of Winnetka, Ill., one of four children of writers William and Mary Lloyd. Robin's father was a conscientious objector to World War II; he moved the family to California for two years so that he could perform alternative service as a firefighter. In 1949, the family relocated again, this time to Switzerland, while William completed his book Waging Peace: The Swiss Experience.

In 1957 and '58, Lloyd attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. As part of the school's foreign studies program, she traveled to Africa with her father, an anti-colonialist campaigner.

Lloyd dropped out of Antioch in her junior year to marry Dan Papish, and then followed him to Brandeis University in Massachusetts. He enrolled in graduate school, and Lloyd earned a bachelor's degree in art history. In 1961, the couple moved to New York City, where Papish became a stockbroker and Lloyd fell in with Manhattan socialists. The marriage didn't last.

In the late '60s, Lloyd earned a master's degree in fine arts from Columbia University. In 1970, while she was working on a film about her then boyfriend, an artist, he took his own life. Devastated, Lloyd finished the film and then moved to Rochester, Vt., where her parents had bought 250-acre Wing Farm.

While teaching art in Rochester schools, Lloyd met Doreen Kraft. The two friends later relocated to Burlington and eventually bought the house on Maple Street where Lloyd still lives. In 1974, they founded Green Valley Film and Art, now the nonprofit Green Valley Media.

- Courtesy Of Jesse Lloyd Guma

- Robin Lloyd with son Jesse at a "die-in" during a renovation of Church Street. Her sign reads, "We are all Hibakusha" (Hiroshima bomb survivors).

In the early '70s, Lloyd and Kraft traveled repeatedly to Haiti and Central America to make documentary films. Their 20-minute animated folktale "Black Dawn" recounts the story of Haiti's liberation from French colonial rule.

In 1976, while working on that film, Lloyd met Greg Guma. At the time, he was an instructor at the Vermont Institute of Community Involvement, which later evolved into Burlington College. (For years, Lloyd was a major donor to the now-defunct college and served on its board of trustees until 2013.) Guma, who'd studied journalism and the history of the muckrakers, said he had read Henry Demarest Lloyd's 1894 book Wealth and Commonwealth but didn't make the connection to Robin until years later.

Guma eventually moved into the Maple Street house. Jesse was born in 1978. Though Guma and Lloyd never married, and ended their romantic relationship, they've remained close friends. Guma has lived in the Burlington home off and on over the years.

In 1979, Lloyd launched the Peace & Justice Center, which focused initially on nuclear nonproliferation.

"The birth of Jesse was a turning point," Guma recalled. "Robin was always a progressive type of person, but ... that really catapulted her into the peace movement."

Now 39, Jesse is married and lives in Manhattan. He recalled that when he was young and his mother went to protests, he was "pretty much at her hip through most of it." In the early '80s, the Burlington Free Press ran a photo of Jesse as a toddler standing over his mother at a no-nukes "die-in" on Church Street.

But he noted that the most seminal experiences of his youth resulted from the near-daily stream of exotic travelers his mother invited to stay in their home.

"Sometimes people stayed for three days. Sometimes people stayed for three months," Jesse recalled. "You never knew what you were going to get, but, amazingly, there was never a bad experience ... As a kid, you don't know that this is not normal."

'Moral Compass'

- Courtesy Of Robin Lloyd

- Left to right: Robin Lloyd; Robin's mother, Mary Norris Lloyd; Jesse Lloyd Guma in the arms of Bernard O'Shea; and Greg Guma at the Nuclear Freeze Rally in New York City on June 12,1982

In 1980, Lloyd ran for Congress on the Citizens Party ticket against incumbent Republican representative Jim Jeffords. Though she was a single-issue candidate, advocating for a nuclear weapons freeze, Lloyd garnered 14 percent of the vote statewide — and 25 percent in Burlington.

In March 1984, Lloyd was one of 44 local activists who staged a three-day occupation of the Winooski offices of Vermont's Republican senator Robert Stafford to protest U.S. military involvement in Central America. At the time, Stafford served on a committee that controlled military funding. In all, 26 protesters were arrested, including Lloyd.

The "Winooski 44," as they were known, included a young peace activist who went on to make her own mark on Vermont: Deb Markowitz, the former six-term Vermont secretary of state and former secretary of natural resources under governor Peter Shumlin.

Markowitz had met Lloyd as a teenager through the Burlington peace movement while attending the University of Vermont. With Lloyd's help, she traveled to Europe to protest first-strike nuclear weapons at "peace camps" that WILPF erected outside of American military bases. Upon her return, Markowitz and her husband, Paul, helped organize the Winooski sit-in.

In a sense, the arrests and ensuing court case put the Reagan administration's foreign policy on trial. Ultimately, a jury acquitted all 26 defendants charged with trespassing, who'd argued that their sit-in was necessary to end the bloodshed in Central America. And, as Markowitz pointed out, the protest convinced Stafford to change his vote to end the military funding.

"Robin was an incredibly important presence because she held the moral compass," Markowitz explained. "She's a quiet, unassuming person. And yet, her leadership in those years was really important."

In the 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Lloyd shifted her activism to other global issues. In 1995, to mark the 80th anniversary of WILPF, Lloyd was among 240 women from 42 countries who rode a chartered "peace train" from Helsinki, Finland, to Beijing, China, to attend the United Nations' Fourth World Conference on Women.

Six years later, she flew to Durban, South Africa, to attend the 2001 World Conference Against Racism. The global progressive movement was feeling optimistic, Lloyd remembered, buoyed by the success of the "Battle of Seattle" in 1999. There, environmentalists, labor organizers and human rights activists had marched together and successfully shut down a meeting of the World Trade Organization.

In Durban, the cause for Palestinian rights and African American reparations took over the agenda. When attendees introduced language that equated Zionism to racism, the U.S. and Israel delegations withdrew from the UN-sponsored event in protest. Nevertheless, Lloyd recalled feeling a sense of accomplishment when she returned home.

She landed at New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport on a clear September morning. As Lloyd got off her plane, the news was just breaking that another airplane had flown into the World Trade Center. On her drive home to Vermont, she listened on the radio as the towers collapsed.

"We knew immediately that everything that had happened at our conference, all the ideas ... were probably going to be buried by the World Trade Center [attack]," Lloyd recalled. "Since 9/11, it's been a battle to even regain a sense of moving forward with the kind of justice structures that are needed."

Crossing the Line

- Courtesy Of Jesse Lloyd Guma

- Robin Lloyd handing out flyers on Church Street with Juan Carlos Vallejo in 2016

After the reelection of George W. Bush in 2004, which Lloyd called "disastrous," she decided to get away from U.S. politics for a while — by going to prison.

On November 20, 2005, at the age of 67, Lloyd was one of 40 protesters who "crossed the line" at Fort Benning. Specifically, she crawled under a wire-mesh fence to issue a "citizen's-arrest warrant" to Col. Gilberto Perez, then-director of the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. Her warrant cited the Universal Declaration of Human Rights — adopted by the UN in 1948 — which states in part, "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."

Lloyd was arrested, charged, fined $500 and sentenced to three months in the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury, Conn. She described it as "a very middle-class way of getting arrested."

As Burlington attorney Baird recalled, "She's the first client I've ever had who wanted to go to jail and didn't want me to help her get out."

What did Lloyd expect to accomplish from her incarceration?

"In part I was doing it to say to people, this isn't such a bad thing," she explained. "Unfortunately, I didn't convince anyone in Vermont to follow in my footsteps."

Perhaps she didn't on that issue. But Charlotte Dennett, a Vermont investigative reporter, attorney and longtime friend of Lloyd's, credits Lloyd for giving her a copy of The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder, by Vincent Bugliosi. Famed prosecutor of Charles Manson and coauthor of Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders, Bugliosi suggested that Americans had a tool to end the war.

"It suddenly hit me that what we could do about it was try to prosecute Bush for this illegal war in a state court," Dennett explained. "So, I decided to take up Bugliosi's challenge."

In 2008, the Progressives recruited Dennett to run for Vermont attorney general. Her platform: If elected, she would prosecute Bush.

"Robin was right there for me, and her [home] office was turned into our campaign headquarters," said Dennett, who later wrote a book about the experience. "It was really a blast!"

Of all the organizations that Lloyd has supported over the years, the one that didn't survive was perhaps the most surprising: Burlington College. As a longtime board member, she endorsed moving the campus to the former Catholic Diocese building. That land-purchase deal eventually resulted in the school's financial collapse.

"Looking back, it probably was an overextension of what we could have managed," Lloyd conceded. "We thought that Jane [Sanders, the college's last president] would have the contacts to make it happen."

Ever the idealist — or optimist — Lloyd suggested recently that the school could yet be resurrected. After reading a recent Seven Days story about arts faculty cuts at UVM, Lloyd and Baird have talked about raising money to hire some of those lecturers to teach classes in a Burlington community center. The model would be similar to a course they organized at Burlington College in 2013, taught by local migrants, former refugees and scholars. Though still a nascent idea, Lloyd cautioned, "Maybe it could rise from the ashes."

At a time when much of America's political attention has turned inward, nationalist and xenophobic, Lloyd said she's kept her activist gaze focused on global solutions. Over the last 15 years, she's participated in five World Social Forums — in Brazil in 2003, Kenya in 2007, Michigan in 2010, Tunisia in 2013 and Montréal in 2016.

Lloyd described World Social Forums as "global think tanks of progressive/radical politics that seek to create an alternative future from capitalist globalization."

How does she keep from becoming disheartened in the age of Trump, when so many of her progressive values are under attack?

"Because of my connections and involvement with people's movements around the world, I don't sink into depression too much," Lloyd explained. "As the Indian [author and activist] Arundhati Roy says, 'Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.'"

'The World Pulls Her'

- Glenn Russell

- Robin Lloyd joining in a song during a Vermont Poor People's Campaign rally at the Vermont Statehouse

About a year and a half ago, Lloyd informed Kraft that she planned to take a one-year hiatus from politics to focus on her art. Kraft was thrilled. As she explained, many Vermonters don't realize that Lloyd is an accomplished visual artist. Soon thereafter, Kraft said, Lloyd enrolled for a residency at the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson.

"And then, a month later, I see my inbox is filled with political messages [from Lloyd]," Kraft said. "I thought, Well, that didn't last long. It's so hard for her to not be an activist. The world pulls her."

Baird agreed.

"She's tried, at times, to stop [her activism], but it's too much in her blood," Baird said. "Somehow, Robin's never been able to give up politics."

"I keep trying to, but it keeps not happening," Lloyd confessed with a laugh.

Currently, she's got plenty of projects on her plate, including the Bread and Puppet documentary. And, as part of her ongoing work with WILPF, Lloyd plans to bring two hibakusha, or Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors, to Burlington for the UN-sanctioned International Day of Peace on September 21.

A cynic might argue that Lloyd is still waging many of the same battles as her storied ancestors did, against war, racism, corporate hegemony and, now, environmental degradation.

What pushes her forward? The recognition, Lloyd noted, that these battles often aren't won in a single lifetime. "And just waking up to the amazing beauty of the world," she added.

Toward the end of her birthday party, Lloyd shared with her guests a dream she'd recently had. In it, she climbed a staircase in a Winooski building still under construction. She arrived at a space where people were lying on the floor with their heads pressed together, forming the shape of a star.

"So, I laid down with them and we put our heads together and had a common dream," Lloyd told her guests. "The trouble was, I don't know what the dream was, because that's when I woke up!"

To interpret its meaning, Lloyd drew from her knowledge of Haitian culture. In Haitian Creole, she explained, the phrase tèt kole translates as "heads glued together" — used to describe people collaborating on a common goal. She then looked around her lush gardens and gave shout-outs to the many friends and organizations she's helped cultivate over the years.

"We're all here," she said with a smile, "with our heads glued together."

Correction, June 27, 2018: An earlier version of this story misspelled Ben Dangl's name.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.