- courtesy of Zack Ekasala

- Terry Ekasala

The Vermont Prize is a collaboration between Brattleboro Museum & Art Center; Burlington City Arts; the Current, a contemporary art center in Stowe; and the Hall Art Foundation, which has a campus in Reading. The prize jury is composed of one juror from each organization, along with one guest juror.

The Vermont Prize is open to individuals and collaborating artists working in any visual medium and living in Vermont. Brandon-based visual artist, graffiti scholar and educator Will Kasso Condry won the 2022 Vermont Prize, the first awarded. Winners receive $5,000, and their work is showcased and archived at vermontprize.org.

Ekasala is an abstract painter who works in oil on linen and acrylic on paper. This year’s guest juror, Chrissie Iles, the Anne & Joel Ehrenkranz curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, noted that in Ekasala’s paintings, subjects are suggested but never fully revealed. “Suspending the image somewhere between abstract composition and storytelling, Ekasala creates interior, psychological spaces that evoke memory and place,” Iles wrote.

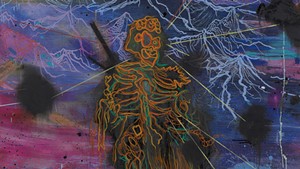

- courtesy of Terry Ekasala

- "Backyard" by Terry Ekasala

So, how does she start?

“I can’t say, 100 percent,” she told Seven Days on Friday. “I don’t think about it.”

At the outset, she can’t know in what direction she will go, she said: “I just start with layers of paint. Like, when I'm doing oils, I just work with layers and kind of make forms. And I just randomly choose colors. And I know it sounds kind of mysterious, but it just starts happening, little by little.”

A big oil painting can take months, she said. “Sometimes it comes pretty quick, but because I like layers and the texture, I tend to work on it for quite a while,” she explained. “I can come to an aesthetic I kind of like, but I don't like the fact that there's not enough texture or paint on the linen, so I have to keep on going.”

- courtesy of Terry Ekasala

- "Making a Run for It" by Terry Ekasala

Ekasala started posting them on social media “just for the heck of it,” she said, and people asked to buy them. “I didn’t intend on sharing them with the world.” But now, when she fills a notebook, she separates the pages and sells them. “They’re literally paying my bills,” she said.

Her other work helps, too, she said, but it’s the notebooks that have allowed her to quit her day job and, after more than 40 years as a painter, work in her studio full time.

Ekasala was born and raised in Weymouth, Mass., where she started drawing when she was very young, she told Seven Days. She attributed “the catapult” of “getting obsessed with drawing” to wanting “to be really good at something in my parents' eyes, in people’s eyes.” Her grandfather orchestrated drawing contests between Ekasala and her cousin.

Ekasala studied commercial art at the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale in Florida. “But I quickly realized that wasn’t for me,” she said. “I did freelance illustration and logos, things like that, but I'd rather waitress or bartend and do my own painting on the side.”

- courtesy of Terry Ekasala

- "Passage" by Terry Ekasala

She set up a studio in Miami Beach in 1983 and moved to Paris in 1987, where she lived, painting and selling her work, for 14 years. While living in Paris, she had an art show in New York. She stayed in Brooklyn for a month and decided to move back to the U.S. She thought she’d live in New York, “but prices were so extreme. Believe it or not, Paris was cheaper,” she said.

A longtime friend who was from the Northeast Kingdom suggested she move to Vermont, which she did in 2001. “I didn't know there were moose up here. I didn't know there were bears,” she said. “I didn’t know it was so isolated. I literally cried when I got off the highway at Exit 23.”

But she stayed. These days, she said, “I want to say that I absolutely love it here.” She works in the studio that British abstract painter Norman Toynton built for himself about 50 years ago. “It’s got great lighting, great space,” Ekasala said, calling it “a dream” to have found it.

Ekasala’s work has been exhibited in Paris, Berlin, Brussels, Sydney and New York, as well as in Vermont. It is on display July 1 through September 3 at the Bundy Modern in Waitsfield as part of “Nor’easter: Terry Ekasala, Rick Harlow, Craig Stockwell.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.