- Courtesy Of Sundaram Tagore Gallery In Nyc/bca Center/sam Simon

- "Hidden Diamond-Saffron" by Anila Quayyam Agha

In 2016, shortly after Heather Ferrell became curator and director of exhibitions at the BCA Center, Seven Days asked her whether she found it important to bring in outside artists. Having spent the previous four years consulting for two major art museums in Doha, Quatar, Ferrell said, "I think we have a responsibility to look locally as well as internationally, while always keeping ourselves grounded in our community."

The Burlington gallery's current exhibition, "Transcendent: Spirituality in Contemporary Art," cocurated by Ferrell and Shelley Warren, fulfills that promise impressively. Of the seven artists included, four are internationally prominent; the rest have national reputations, including two locals. One of the latter is Warren, a University of Vermont senior lecturer in sculpture and drawing whose multimedia installations occupy the lower-level gallery space.

Aside from the local connection, the exhibit is grounded in community concerns in another way. Despite Vermont's reputed indifference to religion, Ferrell suggests that matters of spirituality are coming to the fore here. "I think all of us are searching for something in response to what's going on in the world around us," Ferrell says in a phone interview, be that faith (in the sense of belief) or the divine.

That's happening in the art world, too, she notes. Overturning a long-standing taboo on faith-based art, institutions have lately begun to feature artists whose work is spiritually inflected. In 2019, Hilma af Klint's early 20th-century spiritualist paintings had a major show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago mounted an exhibit on the Crucifixion.

"There's a reason for that growing prevalence," Ferrell says. "Spirituality is something that brings us all together — like art brings us all together."

The art in "Transcendent" doesn't reflect particular religious beliefs, she adds. "It's about the kinship between spirituality and the creative process."

In this case, a focus on the spiritual, sacred and divine in art makes for an exhibition of unusual beauty.

As viewers open the BCA's front door, their gaze is immediately drawn to the light-based installation in the back room. Anila Quayyum Agha's "Hidden Diamond — Saffron" consists of a white room in the center of which hangs a four-foot lacquered-steel cube. (The windows facing City Hall Park have been covered.) The cube is laser cut on all sides with an intricate, bordered pattern inspired by Islamic architectural latticework. Lit from within by a bright yellow bulb, it casts repeated patterns of light and shadow on every surface — ceiling, floor, walls and visitors.

Agha is a Pakistani American artist living in Indianapolis, Ind.; her light-based installations have been exhibited in more than 20 solo and 50 group shows around the world. Among the many dichotomies this work explores is that of inclusion/exclusion. The artist was raised and spent her formative years in Lahore, where women's access to sacred architecture and spaces is restricted; by contrast, "Hidden Diamond" welcomes and includes all who approach.

- Courtesy Of Bca Center/sam Simon

- "Archangel Uriel" by Sandy Sokoloff

If a glimpse of "Hidden Diamond" doesn't lure in viewers, the exhibition's engrossing soundtrack surely will. Two works of video animation by Shahzia Sikander feature scores composed by Du Yun, who won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in music. While Sikander's three-and-a-half-minute "Singing Suns" is experienced with headphones, the soundtrack of her 10-minute "Disruption as Rapture" fills the gallery. It must be the most hauntingly beautiful piece a BCA volunteer docent has ever had to hear on continuous loop.

The animation of "Disruption," reminiscent of Indo-Persian miniature painting, is equally entrancing. According to an exhibition label, the work is "based on the Gulshan-e Ishq (The Rose Garden of Love), a 17th-century poem and manuscript written by Nusrati, who was court poet to Sultan Ali Adil Shah II of Bijapur (Vijayapura, India)." Illustrations of the love story — an originally Hindu tale that was recast as Sufi by the Muslim writer — change and fade into swirls and bursts of petals and other shapes as the music plays. This disruption indeed invites rapture, even dazzlement. Pakistani American Sikander is a 2006 MacArthur fellow based in NYC.

Leonardo Benzant is a Dominican American artist with Haitian heritage who was born and raised in Brooklyn. His suspended tubular sculptures explore a different kind of transcendence: the spiritual practices of the artist's Afro-Caribbean ancestors. Benzant calls his method of applying sheaths of tiny colored glass seed beads to large-scale cardboard tubes "meditative," according to a label.

Two columnar forms, "Encoded Memories" and "Black and Yellow," have a totemic presence. "The Chameleon's Journey" is a bafflingly looped composition 70 inches tall that incorporates coffee grounds.

Benzant, a 2017 Joan Mitchell Foundation award winner, says on the foundation's website that his artworks "draw from the uniquely shared history of code switching, double-consciousness, and multiple narratives that people of African descent have inherited and are compelled to adopt as a survival strategy for daily life."

Two older artists explore spirituality through geometry. Of the three starkly spare works in the show by Zarina Hashmi (born 1937 in Aligarh, India), her woodcut "Fold in the Sky," a half star-speckled, half void-black composition on paper, most evokes another dimension. Zarina, as she is known, made her mark as a major post-Partition practitioner of non-European abstraction. NYC's Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, among other major institutions, have acquired her work.

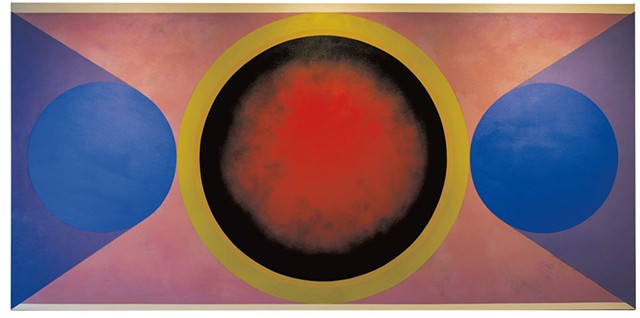

Grand Isle resident Sandy Sokoloff (born 1944 in Brooklyn) explores mystical Judaism — the Kabbalah — in two 46-by-93-inch acrylic paintings in his "Archangel" series. "Archangel Uriel" and "Archangel Raphael" have identical abstract compositions in different combinations of colors. The symmetrical composition features a central sphere with a fiery, turbulent center flanked by two smaller circles that emit rays like flashlight beams, extending precisely to the four corners of the canvas.

- Courtesy Of Bca Center/sam Simon

- "Red Trampoline" by Maïmouna Guerresi

Sokoloff exhibited often in NYC and Boston from the 1970s through the early '90s. He worked in isolation for two and a half decades after that, moved to Grand Isle in 2014 and returned to the exhibiting world with a solo show at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center in 2019. Simultaneously vibrant and tranquil, his paintings explore sacred geometry and the idea that the Archangels represent indirect access to the divine.

Five photographs by Maïmouna Guerresi, an Italian-born artist who converted to Sufism after moving to Senegal, are visually stunning. Two, from her "Aisha in Wonderland" series, show young women covered head to toe in vibrantly colored abayas, made by the artist. They stand at the ends of seemingly free-floating platforms that bring to mind diving boards. Assuming positions that are at once precarious and assured, the women are captured as if in the moment of achieving balance, their graceful hands still slightly outstretched.

Cocurator Warren's work explores Buddhism's spiritual tenets through a combination of sound, projected images and sculpture. In "Pradakshina: A Devotional Practice," a monk walks from right to left across a screen until his image traverses a plain white stupa, or round-tiered monument often used as a reliquary, which the artist has placed between the screen and the projector. His movement thus imitates pradakshina, the practice of circumambulating a stupa to achieve a healing state of mind.

"My motivation is that we live in pretty dark times, with a lot of anger, anxiety, conflicted minds. [I want] to create a space that's peaceful, like a sanctuary," Warren says during a phone call. She has shown work in Washington, D.C., and Kathmandu, Nepal. "One woman says [the room containing Warren's installations] puts her in a really kind state of mind," she adds, "and I think that's what the whole show is about."

Ferrell agrees. "Hopefully, you'll encounter the work and make a connection to it in a way that transcends your everyday experience," she suggests. "It elevates you."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.