- Courtesy Of Stephen And Eve Ogden Schaub

- Rokeby Museum installation

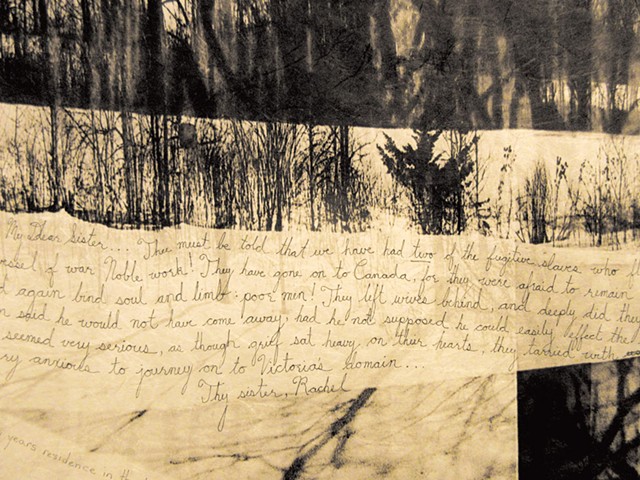

Handwritten on a contemporary, 30-foot-long, black-and-white photograph on display at the Rokeby Museum is the following sentence: "Not a particle of the productions of slave labor, whether it be rice, sugar, coffee, cotton, molasses, tobacco, or flour, is used in her family, and thus her practice corresponds admirably with her doctrine."

The quote comes from a letter written by the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879). He was writing about second-generation Rokeby owner-farmer Rachel Gilpin Robinson (1799-1862), who, with her husband, Rowland Thomas Robinson (1796-1879), sheltered dozens of fugitive slaves at Rokeby. The Quaker couple's work led, in 1997, to the Ferrisburgh property's designation as a National Historic Landmark. It is one of the best-documented Underground Railroad sites in the country.

That quote has a surprisingly contemporary ring, too: Vermonters today still wield their purchasing power for political good. Some buy food from only organic or Vermont farmers, for instance, out of concern for the environment, the treatment of animals or the local economy. Others buy only used clothing in order to lessen the impact on landfills or to avoid supporting exploitative labor practices.

The nexus between past and present created by the photograph — an in-camera collage of Rokeby's buildings and grounds by Pawlet-based photographer Stephen Schaub, inscribed with quotes by his wife, author Eve Ogden Schaub — aligns with the aim of the exhibit it anchors.

The photograph is part of "Rokeby Through the Lens," one of two contemporary art shows that curator Ric Kasini Kadour is bringing to the history-oriented museum. Both exhibits, writes Kadour in his pamphlet "Contemporary Art at Rokeby Museum," "demonstrate how contemporary art can pick up the unfinished work of history and foster civic engagement in social, economic and environmental justice issues." (The second art exhibit, "Structure," opens August 24 and includes sculpture by Vermont artist Meg Walker.)

Former Vermonter Kadour is a self-described "cultural worker" who currently splits his time between Montréal and New Orleans. A collage artist himself, he publishes and does much of the writing for the quarterly magazine Vermont Art Guide, and he produces the monthly Art Map Burlington in conjunction with First Friday Art walks. In the last three years, Kadour has proposed and curated three exhibits with the Vermont Arts Council in its Spotlight Gallery in Montpelier, involving dozens of artists' work, and another at the S.P.A.C.E. Gallery in Burlington.

The idea of bringing contemporary art to the Rokeby came to Kadour a year ago when he visited the museum to research the Robinson family's two artists — illustrator-writer Rowland Evans Robinson (1833-1900) and painter Rachel Robinson Elmer (1878-1919) — for his blog, according to Rokeby executive director Catherine Brooks. Delving into the museum's archives inspired him to explore the origins of the "hundreds" of photographs the Robinsons accumulated over four generations.

When Kadour proposed the novel idea of an art exhibit that integrated his own archival research, Brooks recalls, "We said yes, with no funding." The museum has since applied for funding from the VAC and the National Endowment for the Arts. And Kadour's idea has grown in scope: He has organized a one-day symposium on how artists can engage with history, on June 8, and a four-day Rokeby Artist Lab in late September that will teach other artists how to use the museum's site and archives.

"Rokeby Through the Lens," meanwhile, places past and present photography side by side to encourage today's image-inundated citizens to look more slowly and closely.

The subtext here seems to be nostalgia for a time when photographic images weren't deletable but treasured and preserved. "Today, digital photography has become disposable," Kadour writes in an extensive catalog for the show. "Ironically, there may be less photographic documentation passing to future generations [now than ever before]."

The exhibit includes two contemporary works: the Schaubs' wall-length photograph and Middlebury photographer Corey Hendrickson's set of five enlarged prints of photos of Rokeby farmhouse interiors. The latter were originally published in Yankee Magazine in 2014, accompanying an essay by Leath Tonino; the writer grew up on Robinson Road behind the Rokeby.

- Photo: Amy Lilly

- Detail of "Rokeby" by Stephen and Eve Ogden Schaub

Hendrickson's photos are stark and quiet. Slanting daylight falls on roughly whitewashed walls punctuated by a single painting or on a rifle hung on white-painted bricks. Any visitor who tours the Rokeby house would see the same objects, but in Hendrickson's framing, the simplicity and utility of the décor becomes painterly art in a limited palette of whites, browns and blacks.

Five archival projects by Kadour round out the one-room exhibit. On a small table, a 19th-century stereoscope sits in front of a stereograph of a white-bearded Rowland Thomas Robinson, made in 1874, five years before his death. Kadour writes that an amateur or itinerant photographer likely took the twin-image photo. Viewers can peer (without touching) through the scope to see the two slightly different images resolve into a three-dimensional one.

The curator dubs stereographs "the original virtual reality"; similarly, he invites visitors to think of selfie culture when viewing paired portrait photos of Rowland Evans Robinson. One, taken by the subject's friend in 1887, shows the Walt Whitman-like artist and writer seated in the woods and carving on a fungus with a knife; the other is a commissioned publicity photo taken at a Barre studio in 1893, showing him in tinted glasses — either to hide or emphasize his blindness.

Two vitrines display selections Kadour made from the photographic archives. One contains 10 photos by Robinson's friend Jack Hawley (1843-1922), who "approached photography as a professional," though he worked as a judicial officer and town clerk. Locals will appreciate Hawley's winter shot of the Brick Academy, founded by Rowland Thomas Robinson and others in 1839, with Mount Philo in the background. (The multiracial Quaker school closed in 1846, long before the photo was taken; it was dismantled for its brick in the 1940s.)

Kadour's final display is a collage of prints he made of historic snapshots held together by red yarn looped through their corners. Here the eye wanders from one ordinary scene of local 19th-century daily farm life to another — the prize horse or favorite sheep, a logging scene, a wagon being loaded for a Future Farmers of America Vergennes Chapter event.

But the work that jolts viewers into an immediate understanding of Rokeby's significance is the Schaubs' inscribed, 30-foot-long photo, printed on a roll of Japanese Haruki paper. The couple selected the 16 quotes that are written in the photographed white spaces of Rokeby's preserved buildings and timeless winter wood scape. (One by Kadour, a declaration about artists, can be found among the otherwise historical or history-oriented quotes.)

It's startling to read Rachel Gilpin Robinson's thrilled mention of hosting "two of the fugitive slaves who have fled on a vessel of war," or an announcement that Frederick Douglass would be speaking at an abolitionist convention down the road in "Ferrisburgh Centre" in July 1843. (Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century, a fact Kadour doesn't mention, though it would seem germane to such an exhibit.)

Kadour hopes the show will help viewers "consider the nature of photography" and "think differently about the images they come into contact with on a daily basis," as he writes in the catalog introduction. Whether or not viewers do that, "Rokeby Through the Lens" succeeds in an altogether different arena: enlivening a gem of a museum and the family history it commemorates.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.