- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

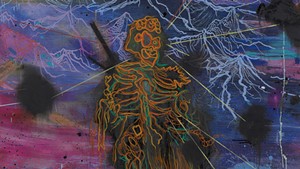

- "Shadow Portrait" by Clark Derbes

Reading, a one-road town in Windsor County with a population of 666 and mainly farms nearby, happens to host one of the best places in Vermont to see international contemporary art.

The Hall Art Foundation, founded by Andy and Christine Hall, consists of a group of five buildings: a 19th-century farmhouse, its three barns and a clapboard house across the road. It is one of three unusual venues the British couple has purchased and meticulously restored to display a collection of some 5,000 works. The others are an industrial shed on the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art campus in North Adams and a castle in Germany.

The Hall in Reading has hosted guest-curated exhibitions drawn from the collection every May through November since 2012. Last year, director Maryse Brand added "Made in Vermont," a show featuring seven Vermont artists' works. Selected by Brand and Andy Hall, the works were offered for sale; Hall added one, by Bennington painter Mark Barry, to his collection.

The second installment of "Made in Vermont" is now on display, this time featuring work of five artists: Arista Alanis, Steve Budington, Clark Derbes, Jason Galligan-Baldwin and Sarah Letteney. Mounted once again in the clapboard house that serves as the foundation's welcome space, the show is the first stop on a guided tour (requiring reservations) that includes in-depth exhibitions of paintings by Malcolm Morley and Richard Artschwager.

- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

- "Switchbacks #17" by Arista Alanis

This year's selection of Vermont works emerged, like last year's, from a pool of artists either known or recommended to Brand and Hall. There appears to be no particular curatorial vision, but certain artists' intentions resonate with others'.

Budington's two paintings and four works on paper explore the implications of translating three-dimensional surfaces into two-dimensional ones. An associate professor of studio art at the University of Vermont, Budington was inspired by the American inventor and idealist Buckminster Fuller's 1954 world map — a flat projection of the globe, centered on the north pole, that took the shape of a long spread of adjoined triangles.

In a Yale University radio interview, Budington notes the impact of Jasper Johns' two paintings of Fuller's map. The abstract expressionist artist painted a faithful copy for display at Expo 67 in Montréal, where it hung inside the Fuller-designed dome that comprised the U.S. pavilion (now known to visitors as the Biosphère). But in 1971, harboring misgivings about the project's assumed factual representation, Johns painted a darker, more ambiguous, 30-foot-long version in charcoal on encaustic.

- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

- "Partial Map With Cloud" by Steve Budington

Budington's 50-inch-tall oil paintings, "Partial Map With Rain Jacket" and "Partial Map With Cloud," echo Fuller's triangular forms and Johns' scale of them while similarly questioning any two-dimensional representation's claim to accuracy. "Cloud" forms a vertically oriented diamond from two triangular wood panels, each painted separately. The lower depicts blue water and a strip of greenery, while the upper affects another dividing line in paint, with a blue sky and cloud sliced off by a shadowed triangle in gray. Each section is depicted from a different perspective, as if the very idea of a flat plane were anathema to mapping.

Budington's 14-by-11-inch works on paper reference a different sort of mapping: medical drawings of the human body's internal organs. Collage renders these works as "partial" as the paintings. In "Folded Figures" and "Fenestration," jumbles of organs (trachea, small intestine, liver), realistically drawn in pencil, are partly hidden by watercolor collage elements: a netlike overlay or a pattern of colorful triangles.

Derbes' distinctive wood sculptures equally subvert visual expectations. The Charlotte-based artist creates his works from locally felled sections of tree trunk that he chainsaws into polygonal forms — sometimes hollowing them out — and paints in geometric patterns. His six pieces at the Hall average 17 inches in height. The visual tension comes from the interplay between the carved surfaces and their painted patterns: Often the latter make it difficult to grasp the form of the work itself.

That trompe l'oeil effect is evident in "Shadow Portrait," whose plaid pattern in a grisaille palette continues around some edges but elsewhere appears to create an edge within a surface. Derbes often makes use of a hunk of wood's natural fissures in his painted patterns or highlights the rough finishes his chain saw leaves behind. An example: "Quilting Bee," a hollowed-out cubic structure whose gouged swirls of sawtooth marks enliven a pattern of colorfully painted triangles.

If there is a playful humor in Derbes' work, Burlington line-drawing artist Letteney has a much blacker one. Her contributions to the New Yorker, such as "The Best Pets for Personal Growth," include humorous text. The Hall's selection of five line drawings gets no help from the written word save in their titles — spelled-out numbers ranging from "Nine" to "Six hundred and three."

- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

- "One hundred and nineteen" by Sarah Letteney

Letteney appears to be as influenced by the unsettling humor and visual economy of Edward Gorey as by surrealism. (One series on her website, "A Is for Accident," is an abecedarian of blood-soaked accident scenes.) "One hundred and nineteen" depicts a couple of human hands prying their way out of the open beak of a blackbird. In "Nine," a hand dangles an eyeball from its skein of veins above the open beaks of three hatchlings. The iris and pupil are trained on the hungry birds, increasing the sense of terrified alertness that the drawing conveys.

Alanis' six small oil paintings, each six inches square, reach for the opposite emotion: jubilance. A staff artist at the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson for the past 24 years, Alanis encapsulates landscapes in bold daubs and rough brushstrokes of brilliant color. Though abstract, her paintings are identifiable compositions of water, sky, orchards, setting suns and other features. Alanis has completed plenty of 6-foot-high paintings; these 6-inch-square selections are part of a series she began in 2014.

- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

- "Let Her Choose Her Own Adventure" by Jason Galligan-Baldwin

Three collages by Galligan-Baldwin round out the show. The Montpelier artist uses vintage illustrations from magazines and his own childhood books to create open-ended narratives. Cues such as the direction of a gaze, an arrow or a strip of text serve to lead the viewer around the composition, but the effect is impressionistic rather than expository. "Let Her Choose Her Own Adventure" appears to empower the figure of a little girl with a still-empty dialogue bubble, while the tiny figure of a woman flees from a pursuing man toward the giant, Roy Lichtenstein-esque face of a crying woman.

As at the Hall itself, it's the adventure that counts.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.