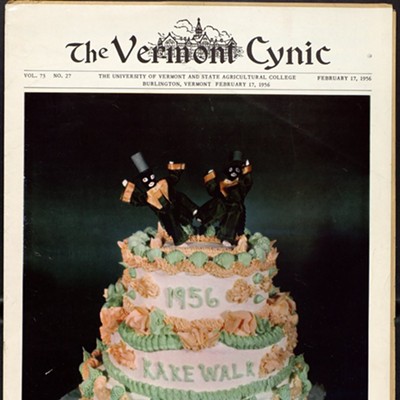

- University of Vermont Special Collections

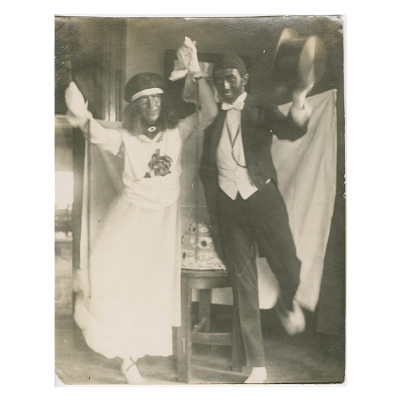

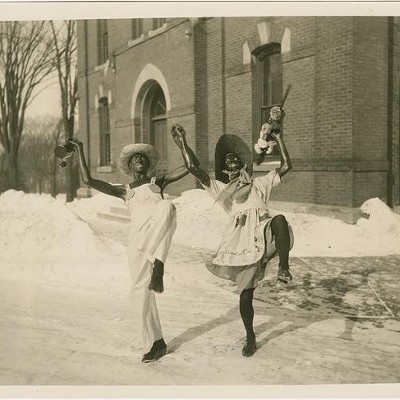

- Kake Walk competitors

When “Meet the Press” needed a guest to counter Alabama governor George Wallace’s segregationist views in 1964, the NBC show called on a progressive leader from Vermont. The late governor Phil Hoff delivered, supporting the new Civil Rights Act “while projecting Vermont’s self-image as a racially enlightened society,” according to the 2011 biography Philip Hoff: How Red Turned Blue in the Green Mountain State.

Yet the governor also appeared more than once before thousands of people gathered at the University of Vermont to watch a popular annual blackface show called “A-Walkin-’Fo-De-Kake,” or Kake Walk. The event was so significant — and accepted — that local and state elected officials handed out trophies and cake to the fraternity brothers who performed best.

The 1963 Kake Walk program listed Hoff, lieutenant governor Ralph Foote, Burlington mayor Robert Bing and UVM president John Fey among the dignitaries scheduled to present awards.

Today, many Americans’ mouths are agape at revelations in Virginia, where the Democratic governor and attorney general both admitted this month to having darkened their faces as young men to portray African Americans. Their admissions followed news stories about Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s 1984 medical school yearbook page, which includes a photo of two beer-clutching men, one in a Ku Klux Klan hood and another in blackface. Northam denied being in the photo, but admitted he did blacken his face when he dressed as Michael Jackson for a dance competition.

The incidents behind the political crisis in Virginia pale in comparison with the blackface tradition at UVM. And though it’s been publicized, and the university library has made Kake Walk materials readily available online, it’s not always remembered quite accurately.

“There was something called ‘cakewalk’ at u of Vermont in the 50’s which involves black face,” former governor Howard Dean tweeted last Thursday. “It was outlawed by the University in the late 50,s [sic] or early sixties because it was seen to be racist.”

Dean, who did not attend UVM, was mistaken on the details. Kake Walk did not end until 1969 — a year after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and president Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law.

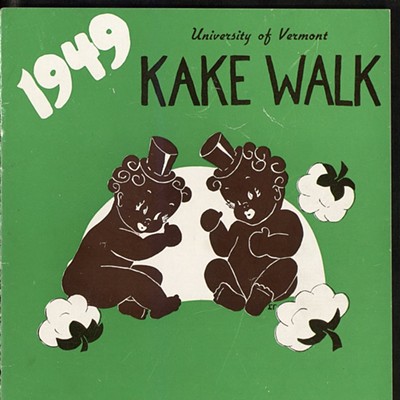

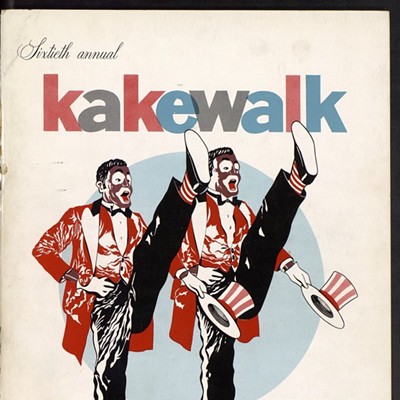

For 80 years, the Kake Walk winter carnival was the heart of the university’s social scene — a winter homecoming of sorts, complete with the crowning of a king and queen. It culminated in pairs of students in blackface performing an exaggerated strutting dance before a cheering audience to the tune of a song called “Cotton Babes.” The best dancers won trophies and multitiered cakes.

“The Kake Walk was an institution at UVM,” one alum, a fraternity brother, recalled in 2016 in the Vermont Cynic student newspaper. “It was legendary.”

The show, and the term itself, had roots in slavery. Before the Civil War, plantation owners organized slave competitions for entertainment and awarded cake to the best dancers. The cakewalk was later incorporated into Jim Crow-era minstrel shows. The blackface performances became wildly popular across the U.S. and reinforced racist perceptions of African Americans.

White Vermonters’ geographic distance from the South did not serve to enlighten them on race, UVM sociology professor James Loewen wrote in 1991 in the first academic essay on the Kake Walk. If anything, the minstrel entertainment made a deeper impression.

“In Vermont, where few blacks existed to correct this impression, the stereotype provided the bulk of white ‘knowledge’ about African Americans,” Loewen wrote. He traced UVM’s Kake Walk to a series of “nigger shows” put on by students in the late 1880s. By 1897, the event had been formalized and dubbed “Kulled Koon’s Kake Walk.”

The inclusion of three Ks in its alliterative name “was no accident,” Loewen wrote.

Fraternities organized the Kake Walk, but the school sanctioned it and Burlington embraced it. The Friday of Kake Walk became a campus holiday, and the event itself grew into a fundraiser. The final performance, in 1969, cost the equivalent of $250,000 in 2016 dollars, the Cynic reported. Local businesses cashed in on the weekend’s crowds. Newspaper editorial boards mostly celebrated it.

“For some students who were there, alums, that’s how they identified with the institution,” said Pat Brown, a retired campus official who has given presentations on the history of social justice and diversity at UVM.

In 1950, the NAACP wrote a letter to UVM’s president protesting the use of blackface, according to Loewen. In 1955, the Cynic, long a booster of the event, called for eliminating blackface and kinky wigs. The paper’s position changed that year after staff interviewed all six black students enrolled at the time. Each of them objected or said the Kake Walk made them uncomfortable.

Walkers were ordered to switch to light green, then dark green makeup in the 1960s. But it wasn’t until the fall of 1969 that an increasingly activist student body was able to halt the event. Black Vermonters, including physiology professor Larry McCrorey and student Linda Patterson, helped lead the charge.

“[A]s late as 1975-76, my first year at the university, I was asked to speak with fraternities that were still trying to bring it back,” Loewen tweeted as the Virginia blackface scandal unfolded this month.

Decades later, the Kake Walk is largely forgotten, and UVM is better known for campus activism in defense of diversity. Student protesters, led by a group called NoNames for Justice, occupied campus buildings last year to demand that UVM do more to eliminate racism. They succeeded in persuading the university to remove the name of eugenicist Guy W. Bailey from what is now the Howe Library.

“That kind of hard work is an example of trying to honestly grapple with history and the past and determine how we want to move forward,” said Beverly Colston, director of UVM’s Mosaic Center for Students of Color.

Nonwhite students now make up about 12 percent of UVM’s undergraduate enrollment. A more diverse campus may be one reason the university is more actively engaged in pursuing racial justice today, Colston said.

In 2010, Robin Katz, then a UVM librarian, organized a course during which students helped curate a digital collection of artifacts and records related to the Kake Walk. The photos, newspaper articles, posters and documents are now accessible on the library’s website. The collection was also used as part of a critical retrospective piece the Cynic published in 2016 that grappled with the racist tradition. The piece won a national award.

Some UVM classes incorporate the material into the curriculum, special collections librarian Prudence Doherty said. Novelist and ’13 UVM grad Simeon Marsalis believes every student should be instructed on the history of the Kake Walk.

“I would like to see it taught,” he said. “Certainly, the community needs to heal, and in order to heal, it needs to have a conversation.”

The Kake Walk figures prominently in Marsalis’ 2017 debut novel, As Lie Is to Grin, about a black UVM student who learns about the school’s former tradition. The novel parallels Marsalis’ own experience: He only heard of the Kake Walk from a roommate during their senior year.

The book, he said, explores what representations of black identity in contemporary culture might have in common with blackface.

“Have we just reproduced the same cultural expression?” he asked. “Can you actually interact with black culture if you’re always interacting with it at its face?”

The Kake Walk still “occupies a controversial position” in UVM’s memory, Katz wrote in an article about her 2010 course. The defunct tradition represents “for some, a hallowed legacy of creativity, school spirit and leadership,” Katz wrote, “and for others, overt racism.”

UVM recently removed Kake Walk committee plaques from the Howe Library entrance. Yet some alums still speak of their participation with fondness. Last fall, for instance, one alumna empathized with former NBC host Megyn Kelly after she was axed over an on-air comment in which she questioned whether blackface Halloween costumes were racist.

“Megyn, I feel so upset at the treatment you are getting from the do gooders,” the alum wrote on the public Facebook wall for Megyn Kelly TODAY. “I graduated from UVM (Vermont) and participated proudly in Kake Walk. This BS going on hurts people like you and me.”

Unlike some other blackface events, the Kake Walk did not have repercussions for people, including politicians, who took part or attended. The event happened in front of crowds of thousands who packed Patrick Gymnasium and cheered in approval.

“It seems like it would be hard to pull out one individual,” librarian Doherty said. “It was a collective bad decision for years.”

Correction, February 14, 2019: An earlier version of this story misquoted Simeon Marsalis. The quote has been fixed to read: “Have we just reproduced the same cultural expression?”

Related Stories

-

The Charlotte Blues: Small Town Paper’s Editor Departs After Reporting Zoning Dust-Ups

By Dave Gram March 23, 2021

-

Superintendent Sean McMannon Is Teaching Winooski About School Spirit

by Molly Walsh May 1, 2019

-

Vermont Senate to Vote on Amending Slavery Clause in State Constitution

by Taylor Dobbs April 12, 2019

-

Letters to the Editor (2/27/19)

by Seven Days Readers February 27, 2019

-

Letters to the Editor (2/20/19)

by Seven Days Readers February 20, 2019

Related Slideshows

Speaking of...

-

UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza

Apr 28, 2024 -

Records Show UVM Professors Questioned Decision to Nix Palestinian Writer’s Appearance

Dec 20, 2023 -

UVM Strikes Deal With Burlington That Could House More Students on Campus

Dec 18, 2023 -

Burlington Area Selected as Semiconductor 'Tech Hub'

Oct 25, 2023 -

UVM Students Protest Cancellation of Palestinian Writer's Appearance

Oct 24, 2023 - More »

Comments (15)

Showing 1-15 of 15

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.