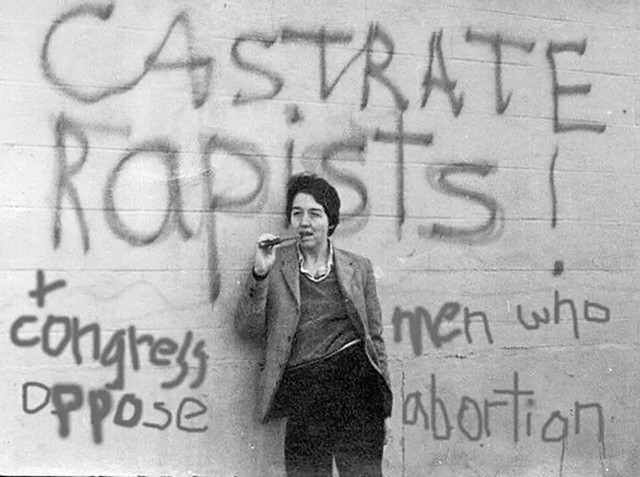

- File: Courtney Lamdin

- Peggy Luhrs in June 2021

Throughout most of her 76 years, Peggy Luhrs appeared to relish conflict. "My enemies certainly make me feel good about myself," she declared to the marchers assembled in City Hall Park for Burlington's first Pride celebration in June 1983, of which Luhrs was a key organizer. "If the warmongers, witch burners and moral majority types who don't mind starving children but hate gays are against us, we must be doing something right."

For Luhrs, who died last month of pancreatic cancer, doing something right meant being a public agitator for causes that mattered to her. In more than half a century of activism, she helped build some of the institutions that still support women and the LGBTQ community in Burlington. HOPE Works, formerly known as Women Against Rape, began in 1973 as a nighttime hotline for survivors of sexual violence that Luhrs and her fellow volunteers operated out of a living room in the Old North End; Steps to End Domestic Violence was originally conceived, by Luhrs and others, as a peer support network called Women Helping Battered Women.

From 1985 to 1995, Luhrs put feminism on the city hall agenda as the first executive director of the Burlington Women's Council. She was paid a modest stipend to have an opinion, and when she spoke, people generally listened, even when they didn't like what she had to say.

"Peggy raised the consciousness of this community about women in a way that very few people have done," said Sandy Baird, a lawyer and former Democratic state representative who met Luhrs in the '70s through a feminist group.

By the time she died, Luhrs had only grown fiercer in her conviction that the opprobrium of her enemies affirmed the rightness of her thinking. But in her final decades, the targets of her vitriol increasingly resembled the marginalized groups for whom she'd fought decades earlier. As the culture around her warmed to the idea that womanhood might mean something more than chromosomal inheritance, she became convinced that trans people were out to colonize women's enclaves.

When her political allies began to turn against her, she seemed to project her personal sense of embattlement onto the whole fragile ecosystem of women's bars, women's bookstores, women's solidarity networks and, above all, women's freedom to exist apart from patriarchal interference.

On her Facebook page and in her weekly television series for the Center for Media and Democracy, "Feminist Media Review With Peggy Luhrs," she would rail against trans activists who, in her mind, were attempting to subvert the gay and lesbian rights movement she had created in Burlington. In one 2017 segment, she referred to them as "twerps who don't even know whose shoulders they're standing on"; during the same episode, she compared former president Donald Trump's self-aggrandizing rhetoric to gender-neutral vocabulary, suggesting that both kinds of language were instruments of totalitarianism.

In 2020, she attempted to hold an event at the Fletcher Free Library on "the unforeseen consequences of the transgender agenda," which she canceled due to backlash. When she ran for Burlington City Council the following year, she lost to Perri Freeman, who is genderqueer and an outspoken advocate for trans rights, by more than 1,700 votes.

As a result of her public crusades, Luhrs won the admiration of some Republican men in the last chapter of her life. She was an ardent supporter of Christopher-Aaron Felker, a gay Burlington City Council candidate who was widely condemned for his transphobic social media posts. After Luhrs died, Bradford Broyles, a right-wing impresario and TV producer who managed Felker's campaign, tweeted a fond remembrance of her. "Biological males, trans women, competing in sports, I believe, harms women's sports, because I think it infringes on the ability of biological women to succeed in their own endeavor," Broyles told Seven Days. "We were kind of lockstep in support of those sorts of causes."

Over the last decade, Jackie Weinstock, an associate professor in the University of Vermont's gender, sexuality and women's studies program, tried to engage Luhrs in discussions about her resistance to recognizing trans women as women. To Weinstock, Luhrs represented a case study in the growing pains of the lesbian movement and the ideology of trans-exclusionary radical feminists, or TERFs, a vocal minority within the feminist movement that uses scare tactics to advocate for banishing trans women from women's spaces.

According to Weinstock, Luhrs was deeply preoccupied with what she perceived as societal pressure for people to come out as trans or nonbinary rather than as a butch lesbian. (Luhrs was personally fond of the term "dyke.") Luhrs also voiced the fear, amplified within her social media echo chamber, that lesbians would be denounced as "terrorists" if they weren't attracted to trans women.

"She was expressing a lot of hatred, and then she got hatred back, and I think that just reinforced for her that all of this work towards equality and social justice for women and lesbians was going backwards," Weinstock said.

When Weinstock would point out to Luhrs that her moral panic over the inclusion of trans people in the LGBTQ community mirrored the pious indignation of the Christian right over the gay and lesbian marriage equality movement, Luhrs would always insist that she supported "trans rights," as if trans rights were somehow distinct from the validity of trans existence.

"I'd tell her, 'Do you understand that you're aligning yourself with the anti-trans folks on the right?'" Weinstock said. "And she'd say, 'We make strange bedfellows, but I'm not coming at it from that perspective. I'm coming at it from the feminist perspective of protecting women as an identity and as a group.' She had these essentialist notions about women, and biology was a core part of that."

Dana Kaplan, the executive director of Outright Vermont, declined to be interviewed about Luhrs. "Her anti-trans views were hurtful, but not in a vacuum — and reflect the work we have to do towards progress," Kaplan wrote in an email.

Shay Totten, whose son is trans, said he couldn't understand why Luhrs, a lifelong champion for human rights, would dedicate so much energy to attacking one of society's most marginalized groups.

"I hope that her loved ones and family have time to grieve," said Totten, a former Seven Days columnist who now works for the American Press Institute. "But at the same time, she was a very angry and hurtful person who was doing serious harm, and that can't be lost. I mean, the last few years of her life, she was really on a mission."

Born, again

- Courtesy Of Lynn Vera

- Peggy Luhrs

Luhrs, the eldest of four sisters, was born in Los Angeles in 1945, just before the end of World War II. Her family moved around for her father's post in the Merchant Marine before they settled in Saugerties, N.Y., where Luhrs grew up.

Her father was hard on all the women in the house, according to Oak LoGalbo, Luhrs' longtime friend and former partner of more than 15 years, but he saved his sharpest rebukes for Luhrs, of whom he seemed to expect the passive good manners of a future housewife. "He'd threaten to cut off all her hair if she was acting tomboyish," LoGalbo said.

In high school, Luhrs met her future husband, Terry. After she graduated, she studied architecture and design at the Pratt Institute in New York City before she and Terry moved to St. George, Vt., in 1969, for his job at IBM. The following winter, Luhrs gave birth to a son, Justin. (He declined to be interviewed for this story.) Luhrs had dabbled in feminist circles in New York City, said LoGalbo, but in the loneliness of caring for a child in a small trailer home, hemmed in on all sides by snowdrifts, she underwent a radical awakening.

In 1971, she and several other young mothers in the Burlington area started a weekly consciousness-raising group to process their personal and political frustrations in the absence of men.

For Luhrs, this kind of unfettered communication with other women was a revelation. "Peggy felt very isolated, and many of us did, because the men in our lives were working," said Baird, who was part of the consciousness-raising group. "We formed our own daycare groups. We talked about our lives. We formed political action groups."

Luhrs and Baird soon got involved in Wages for Housework, an international movement that originated in Italy, in the early '70s, to demand compensation for the unpaid domestic labor of women. In 1972, the year before the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade, Luhrs and Baird helped launch the Vermont Women's Health Center, the first clinic in the state to offer safe, legal abortions. (The clinic would later become the target of the anti-abortion campaign Operation Rescue, whose flyers described the Vermont Women's Health Center, according to a 1990 New York Times article, as "a coven of lesbian witches.")

Around that time, which Luhrs has chronicled in various essays, she read "The Woman-Identified Woman," a manifesto that first made the rounds at the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City, in 1970. The authors, who called themselves the Radicalesbians, argued that heterosexuality stunted women psychically and politically, and that the solution to the whole patriarchal mess lay, ultimately, in purging their beds of men.

Luhrs, who had already left her husband, embraced the assignment. By 1973, she had come out as a lesbian.

"In a dream I had at the time I rode a motorcycle and then jumped over a fence and ran through an open field," Luhrs wrote in a 2019 essay for Vermont Woman. "I understood so much of my past angst, and I was happier than I could remember."

Defining the front lines

- Courtesy Of Lynn Vera

- Luhrs and her son, Justin

Over the next few decades, Luhrs molded herself into one of the more truculent fixtures in the Burlington lesbian-feminist scene. She joined a women's collective in the late '70s that published a monthly-ish newspaper, called Commonwomon, deliberately misspelled so as to rid the suffix of any lingering testosterone. In essays and articles, Luhrs refined what would become her signature brand of polemical diatribe. Her primary subjects were the patriarchy, capitalism, militarism, colonialism, and any other ism she found repugnant, oppressive or lacking in rigor.

In her June 1979 report on a women's conference, Luhrs dispatched the marquee presenter, Betty Friedan, as if she were reviewing a particularly underwhelming Woody Allen movie: "She was a poor speaker, something I didn't expect, rambling and confused. In a room full of a thousand women, it felt like she addressed the four men in the front row."

Luhrs' incendiary style caught the attention of Bob Bolyard when he was visiting Burlington in 1985. "I passed city hall, and there was a political protest with a short, angry woman yelling about something," he said. "I don't recall what the topic of disagreement was, but I remember the energy of the woman and the crowd and thinking, I want to move here."

Bolyard did move to Burlington, and in the mid-'90s, he and Luhrs clashed over inviting then-lieutenant governor Barbara Snelling to speak at Pride.

"There was an uproar from the feminists, led by Peggy," Bolyard wrote in an email. "Yes, Mrs. Snelling was a woman...but she was a REPUBLICAN!!! And we can't have a Republican speak at Pride!" In the end, Luhrs prevailed, and Snelling was canned as a guest.

"Peggy was never boring," said Bolyard, who performs in drag as his alter ego, Amber LeMay. "Peggy got people to follow her or speak out against her — either way, it made for a more lively community."

Luhrs enjoyed being provocative. In 1986, she and a group of radical feminists, who called themselves, spoofishly, Ladies Against Women, showed up at a Memorial Auditorium event featuring Phyllis Schlafly, a national leader in the conservative effort to thwart the women's liberation movement and the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. At one point, Luhrs, dressed as a 1950s housewife in a matronly blouse and frilly hat, went up to the microphone to ask Schlafly a question.

"I know that Mrs. Schlafly is against abortion, but I'm very concerned about birth control. Right on every street corner in America, in our drugstores, are little rubber concentration camps in which sperm die every day!" Luhrs shrieked, waving a condom in the air. "I'd like to know what Mrs. Schlafly wants to do about this!" Schlafly responded dryly: "It's a free country. You can do whatever you want."

Whenever there was a political action in Burlington, Luhrs usually would be on the front lines, said Joy Livingston, her friend of several decades. "If she wasn't in charge of whatever was going on, she'd have a speech to make or an analysis to offer that was always right on," Livingston said. "She was not afraid of women's anger, which was an amazing gift she gave to all of us."

Luhrs' anger occasionally got her into legal trouble. In 1990, when anti-abortion demonstrators barged into the Vermont Women's Health Center and chained themselves to filing cabinets, Luhrs started a fight with a protester and ended up being charged with simple assault.

Several years later, Luhrs got into a heated spat with Jennifer Matthews, who succeeded her as executive director of the Burlington Women's Council. According to LoGalbo, Luhrs' former partner, Luhrs felt that Matthews was too moderate in her views and that her appointment had been a rebuke of Luhrs' politics. Following one particularly testy council meeting, as Seven Days political columnist Peter Freyne reported at the time, Luhrs allegedly charged at Matthews and shouted at her, "You scared? You scared, you fucking bitch? Are you scared of me?"

Glo Daley, who met Luhrs through the Burlington lesbian community in the '70s, remembers Luhrs' anger as a sharp instrument that she often wielded indiscriminately. "I respected her, but I didn't always enjoy her company," said Daley, 81.

Luhrs, a skilled carpenter, built Daley's first house, and the two often attended protests and demonstrations together. During a rally in Burlington some years ago, Daley said, Luhrs lost her temper at a speaker.

"I can't remember what it was about, but Peggy started screaming and yelling because she thought they were off a tiny little bit," said Daley, who was with her in the crowd. "And she was furious with me, because I didn't agree with her screaming at this guy, who I thought was saying something pretty compassionate."

On the outs

- Courtesy Of Lynn Vera

- Luhrs and Lynn Vera at the Phyllis Schlafly protest

As Luhrs got older, her militancy took on a paranoid fervor. In 2013, Rachel Siegel, who had recently become the executive director of the nonprofit Peace & Justice Center, bumped into Luhrs at City Market, Onion River Co-op. According to Siegel, Luhrs launched into a tirade about the lack of literature and programming focused on "women" — by which Luhrs meant cisgender women — at the Peace & Justice Center, where Luhrs attended meetings of the local chapter of the Women's International League for Peace & Freedom.

"She was really angry, ranting and raving that we didn't have more stuff on lesbians and gender issues, and that we only had stuff on trans people, which just wasn't true," recalled Siegel, who left her job at the Peace & Justice Center last year.

In August 2018, Luhrs organized a special gathering of WILPF at the Peace & Justice Center to discuss, in the words of the event description, "today's feminist movement and the possible erasure of females within the movement."

When Siegel and her staff saw the meeting agenda, they panicked. "We were like, 'Oh, shit. We're hosting an event that's anti-trans,'" Siegel said. She called Robin Lloyd, one of the founders of the Peace & Justice Center and a member of WILPF, and asked the group to hold the discussion elsewhere. Instead, Lloyd said, WILPF members took a vote and overwhelmingly moved to proceed with the event as planned.

Lloyd, 84, a longtime anti-war activist who has been friends with Luhrs since the late '70s, was puzzled about why a discussion of "female erasure" might be considered anti-trans. She said she feels, perhaps less vehemently than Luhrs, that the gender-neutral lexicon has eroded the specificity of her own experiences.

"Now you can't talk about women being pregnant. You have to talk about people being pregnant," she said. "I think, and the others in WILPF agree with this, that that's carrying it too far. We are proud to be women, and it's just very hard to accept that what women have fought for is now being kind of diminished by calling us 'people' instead of 'women.'"

After the female erasure talk, Siegel and her staff members decided that Luhrs should be barred from attending the Peace & Justice Center's March 2019 gala at the ECHO Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, where Lloyd would receive a lifetime achievement award.

"We had staff and volunteers who didn't feel safe around Peggy," said Siegel. "She had written enough scary things online and carried posters at Pride parades that said, literally, 'Fuck t— rights.' It would be like if you were a Black person and there was an active white supremacist in the community. You wouldn't have to be targeted directly to be scared."

Siegel called Luhrs and asked whether she would be willing to celebrate Lloyd's award at a different time. According to Siegel, Luhrs responded by storming into the Peace & Justice Center's headquarters on Lake Street and shouting at unsuspecting volunteers that the entire organization was fascist. Fearing that Luhrs might create a disruptive spectacle at the gala, Siegel said, the staff and board collectively decided to call the police if Luhrs tried to get in.

"As an abolitionist organization, we were hesitant to utilize the police for anything," Siegel acknowledged. "It's the most conflicting thing I've ever done. And I still don't know if I did the right thing."

On the evening of the gala, Luhrs rolled into the ECHO Center with her camera-wielding friend, Bill Oetjen, a prolific vector of transphobic propaganda on social media. Oetjen's 12-minute video of the encounter, which had received 43 views on YouTube as of Monday, shows Luhrs approaching the entrance to the auditorium, where several people had blocked her way.

"What are they afraid of?" Luhrs asked, addressing no one in particular. "I've done no harm to anyone."

"Yes, you have, Peggy," someone answered somberly. "You know you have."

"No, I haven't!" Luhrs retorted. "If you think speech is harm, if my having a different opinion is harm, that's ridiculous, and that's why I'm so against this." After a beat, she added: "Stalinism! Stalinist Left is what we've got here!"

Eventually, another person told Luhrs that he was the proud father of a trans child. "I'm sure you are," Luhrs said derisively. She proceeded to make an obscene reference to the genitalia of transgender rights advocate and reality TV star Jazz Jennings.

"You do understand that that's hurtful speech, don't you?" the person said calmly.

"Well," Luhrs replied, visibly wounded, "the way you're keeping me out is hurtful."

One of Luhrs' longtime friends, Lynn Vera, was in the auditorium. When Vera got wind that Siegel had called the police on Luhrs, she said, she came out and confronted Siegel. "I said to her, 'You never call the police on another woman," recalled Vera. "That's not how community works. That's not how women's community works."

A few minutes later, a police officer arrived. After a brief exchange with the officer and a few more indignant outbursts ("I started the LGB community here, before the hostile takeover by the T!"), Luhrs finally left with Vera, flanked by a small entourage of supporters.

'Terrific sadness'

- Courtesy Of Joy Livingston

- Peggy Luhrs

For almost two years, Lloyd assumed that Luhrs was angry with her for not boycotting the ceremony. The whole incident left a bad taste in her mouth, she said, and she withdrew her annual contribution to the Peace & Justice Center.

When Lloyd visited Luhrs at the McClure Miller Respite House the day before she died, Luhrs was in a coma. But Lloyd was relieved to learn from Vera, who was also at Luhrs' bedside, that Luhrs had supported Lloyd's decision to accept her award that night. "When someone dies and you feel that something has been unresolved...," Lloyd trailed off. "Anyway, I have the feeling now that it's more resolved than I thought."

Siegel's relationship with Luhrs, however, was broken beyond repair. "The last time I saw Peggy, which was maybe two months ago, she flipped me off," Siegel said wearily. "I've known Peggy since I was a teenager. Her son and I are the same age and grew up in adjacent towns. And I've had a lot of respect for her. I did for a really long time. And I still have a lot of respect for the work that she did in the '70s and '80s. She had a big impact."

"There are a lot of what I consider Peggy apologists, and I consider myself as having been part of that group for a while," Siegel continued. "Those people might not have agreed with her, but they thought her behavior was excusable because she had done so much good. But now, I don't think it's excusable. I think we can hold both truths. She did good, and her behavior became unacceptable."

In Luhrs' final days, said Baird, her compatriot in the Burlington women's movement, she didn't seem to be at peace. On her deathbed, Luhrs told Baird that she was afraid — but what she feared, precisely, Baird couldn't decipher.

"She told me she feared violence, but I think the main feeling she had was terrific sadness, feeling cut off from people that she felt were her friends," Baird said. "That's how she died. Except that she knew many, many people — women and men — who supported her. Many, many people, but they don't want to speak out about it."

Correction, March 14, 2022: A previous version of this story mischaracterized a social media posting by Christopher-Aaron Felker, which was transphobic but did not contain a slur.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.