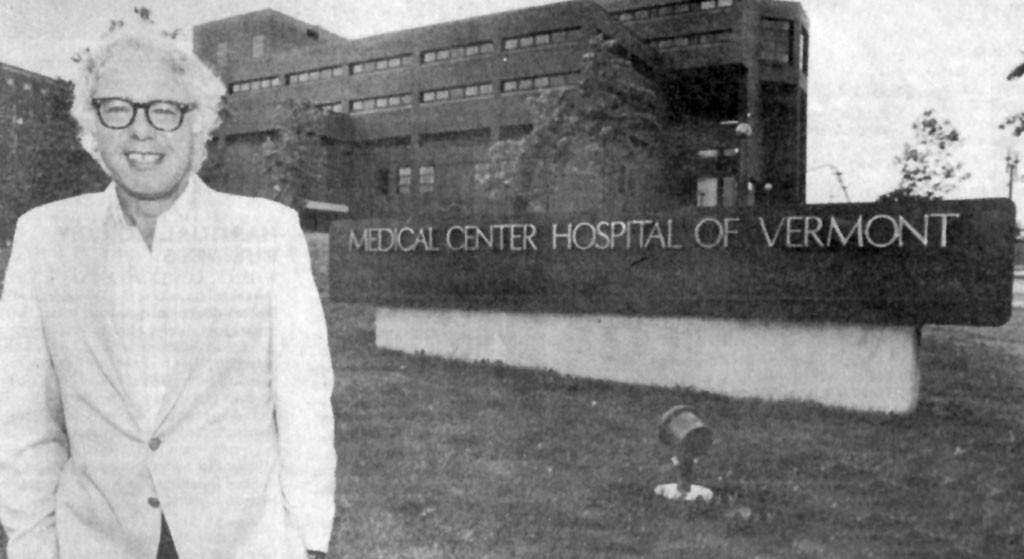

- photo courtesy of Vanguard Press

- Bernie Sanders circa 1987

Burlington Mayor Bernie Sanders didn't attend the June 1987 press conference that opened with a bombshell. Assessor Rosaire Longe did his bidding, announcing that the city had sent a tax bill to the Medical Center Hospital of Vermont, the venerable institution on the hill now known as the University of Vermont Medical Center. The amount the Sanders administration sought from the hospital, which, as a charitable institution, had been considered tax-exempt: $2.9 million.

Spencer Knapp, the hospital's legal counsel then and now, was in the president's office when the hefty bill arrived. "Our jaws dropped to our chests," he recalled.

A couple of hours later, hospital president James Taylor stood before news cameras to denounce the Sanders' plan to "put us on the tax rolls." He vowed: "We will not pay the bill. We will pursue all the channels proper and appropriate to protest it."

Sanders himself publicly weighed in with a press conference the next day. He argued that seeking taxes from the medical center was about fairness for taxpayers. The hospital had a $100 million budget, he said, but paid "nothing in taxes, nothing in lieu of taxes and nothing for the services they receive," meaning fire, police and other municipal protections.

He threw jabs about the hospital trustees meeting behind closed doors and administrators' salaries: "There are a heck of a lot of people up there making a heck of a lot of money," he said pointedly.

A reporter asked Sanders if taking on a respected institution was politically risky. After squeaking out a 10-vote victory to capture the mayor's office in 1981, he had been reelected mayor twice by comfortable margins — but Sanders had statewide ambitions.

He replied, "I have to do what I think is right."

In a telephone interview nearly 30 years later, Taylor said what was upsetting about the tax bill was "having it show up without any prior discussion." He recalled that hospital officials appreciated that Burlington had a significant percentage of tax-exempt properties. At the time, however, the concept of hospitals making payments in lieu of taxes wasn't an established practice, he said, adding, "We did have some reluctance to do anything that would put pressure on others."

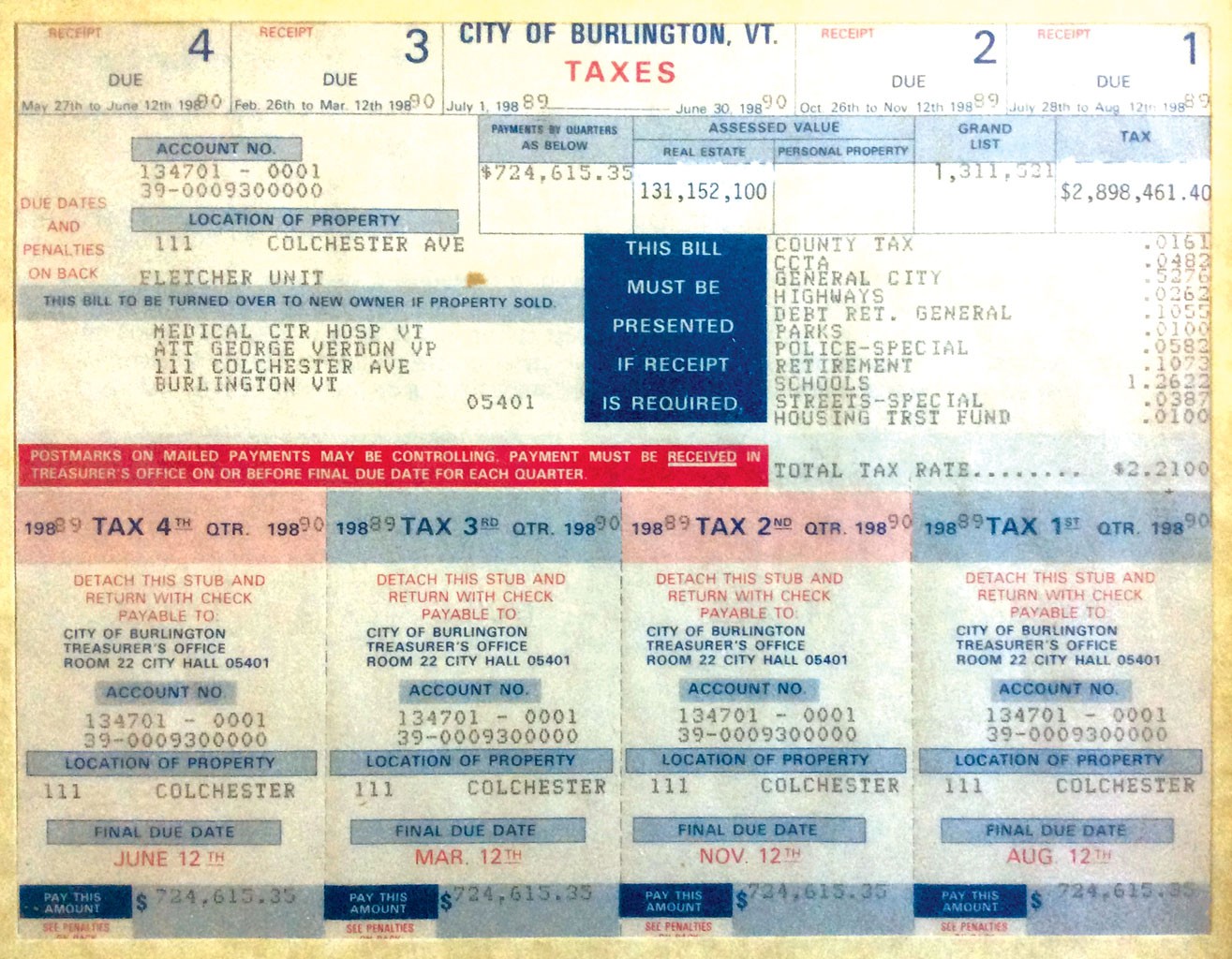

- A Burlington tax bill sent to the Medical Center Hospital of Vermont

Hospital officials claimed moral high ground in the 1987 tax fight. A July 1 hospital newsletter argued, "The effects of stripping the hospital of its tax-exempt status are far-reaching. The first to suffer would be patients. The finance office estimated the cost of the average patient stay would increase by about $300."

The hospital went to court "in a week," Knapp said, suing to stop the city from collecting the tax. The first payment of more than $724,000 was due soon.

Sanders had begun challenging the medical center soon after he became Burlington's mayor in 1981. In a September letter that year to Herluf Olsen, then the hospital president, Sanders laid out his view of the institution's role: "The essence of what we are presenting is a request for a change of spirit on the part of MCHV toward our community. We want MCHV and the physicians associated with it to begin taking a more active role in community health care by using their vast resources for the common good."

The mayor found ways to pressure the hospital. He opposed its plan to expand to 450 beds in a new building, arguing that it would raise rates for patients. The hospital scaled back the project. Sanders also testified against the hospital's budget increases in proceedings before regulators.

Jeanne Keller, hired by Sanders as health insurance administrator, recalled the first time she saw the mayor try to extract support from hospital officials. He invited the hospital's trustee chair, the medical director and the CEO to meet him at a free clinic in Burlington's Old North End. The health center needed money, and the mayor was trying to help, Keller said.

"These guys had to sit in the waiting room to talk with the mayor," Keller recalled.

In the meeting, Sanders first invited the center's staff to describe its needs. "And then Bernie did his Bernie thing to them," Keller said. He asked why the hospital couldn't supply a doctor once a week to supplement the center's staff. "I was just in awe," Keller said. "That fearlessness."

Although she doesn't remember if anything came of it, Keller said, whatever the response, "it wasn't much."

Sanders appointed a task force to seek out new sources of revenue for Burlington. When its members suggested taxing the hospital and the University of Vermont, Sanders and what was then known as the city's board of aldermen put the question to voters in March 1986. Voters said yes, but the state legislature refused to approve the city's proposed charter change.

Sanders continued to push in 1987. He tried, without success, to force the medical center to match a city grant to support the Visiting Nurse Association. He asked the Vermont attorney general if it was legal for the hospital trustees to meet behind closed doors. He set up another task force — this one to look at health care — and gave them a mission, found in written form among his papers: "It seems to be that the question that must be debated in our community is a very fundamental one and that is, 'Should the practice of medicine, and the whole health care system, be run as a corporate business generating huge profits and incomes to higher-ups in that profession, or should health care be a right to which all Americans are entitled at the lowest possible cost?'"

Ultimately, the assessor sent the hospital a tax bill, and the hospital sued. The court fast-tracked a trial, which ran several days in August 1987. The city asked the court to declare that the hospital was taxable, or that portions of it were taxable, or that a public vote was required for it to receive an exemption from property taxes.

"We took the view they didn't provide enough charitable care to qualify" for a tax exemption, Joseph McNeil, then city attorney, said in a recent interview. The hospital had provided $1.5 million in free care, but "much of what they were calling charitable care was really uncollectable debt," McNeil said. Translation: hospital bills that people couldn't pay.

Superior Court Judge John Meaker issued his decision on September 22, ruling against the city on all counts.

"For Judge Meaker, essentially, the hospital is charitable because it is a hospital," Sanders complained in statement he released at the time. "If an institution provides virtually no free care to the poor, hounds people for payment and destroys credit ratings and has executives and physicians associated with the hospital earning very large incomes — how in any common-sense understanding of the word can this institution be described as 'charitable'?"

"Taking on the establishment and fighting for social change — in this instance a fair tax policy for Burlingtonians and a hospital policy which will show compassion for the poor — is not an easy task," Sanders said in the same statement. He persuaded the aldermen to appeal the ruling to the Vermont Supreme Court. The city lost again.

Still, McNeil said, Sanders' challenge ultimately paid off. "We lost — in a legal sense — but we gained ground in the sense that the result was both [the hospital] and UVM have entered into fee-for-service agreements with the city ... It was only this action that provided the political discussion and notoriety. It was the catalyst for a better result that has lasted to the present."

By the time the city and hospital reached a 30-year agreement on payments, in 1999, Sanders was a congressman representing Vermont. Knapp recalled that the deal was negotiated while the hospital was starting its Renaissance Project — a makeover and expansion that would eventually cost more than $350 million. At the time, Knapp said, the city had "considerable leverage" because the medical center needed local permits. Later, the project took a criminal turn, and the hospital's CEO took a plea for conspiring to defraud a state regulatory agency. The institution's public image reached an all-time low.

Since its first payment of $325,000, the hospital's annual fee-for-services bill has grown to $446,000; the amount automatically increases by 2 percent each year. Elsewhere in the country, many major nonprofit institutions now contribute to city coffers in return for the municipal services they receive.

And today, the medical center provides about $9 million in charitable care, not including uncollectable debt. The quarterly board meetings have been open to the public since at least 1995, according to medical center spokesman Mike Noble. And the city's infamous tax bill is framed. Knapp found it pretty easily among his things at the office.

John Franco, who was assistant city attorney in 1987, said Sanders' campaign against the medical center sowed the seeds for his vision of universal health care. The tax battle spotlighted the shortcomings of the U.S. health care system, such as the high cost of health insurance and access to care based on what people can afford, he said. In its appeal of the tax case, the city challenged the judge's reliance on the hospital's assertion about its open-door admission policy. The city argued that it could have provided testimony from patients who were denied admission because of their inability to pay.

Neither Sanders nor his campaign or Senate staff would talk about this bit of history or comment on what it says about how he might govern now that he has set his sights on the nation's highest office.

But Terry Bouricius, a Progressive alderman in the 1980s, had plenty to say. He said the tax fight showed Sanders' values when it comes to tax burdens and income disparities. Trying to tax the hospital was a way to shift the burden of the regressive property tax from city residents. Bouricius said that fair taxation has always been a moral issue for Sanders.

Erhard Mahnke, another 1980s alderman, agreed there is a "clear thread" running from Sanders' hospital tax fight to the present: "He is not afraid to challenge the establishment, and he cares very deeply about ordinary Americans."

At 73, Sanders continues to use electoral politics — the collective will of voters and his rhetoric — to try to force large and powerful institutions to change.

"He is all about building movements," said Keller, who worked for Sanders from 1981 to 1986. Bold initiatives, such as presenting a $2.9 million tax bill to the state's largest medical center, "draw attention to the possibilities," she said. Today, as Sanders crisscrosses the country in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, Keller said, "His message to these crowds is, we have to build a movement ... a movement that will keep the pressure on, no matter who is president."

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.