- Sarah Cronin

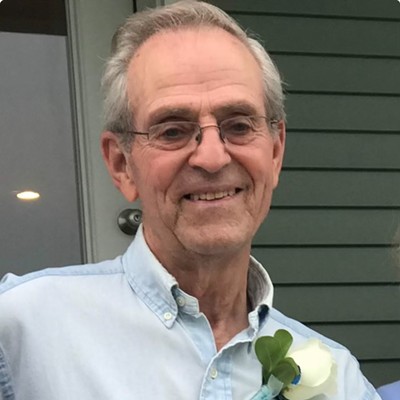

As a therapist who wants to use the psychedelic drug psilocybin in his practice, Rick Barnett of Stowe walks a fine line. He advocates for legalizing the therapeutic use of psychedelics, but he understands that some peers in the medical establishment are skeptical about drugs such as psilocybin, ketamine and MDMA.

With psychedelic therapy gaining prominence, it's becoming easier for him to walk that line. On September 21 and 22, Barnett, who has a doctorate in clinical psychology, led a national conference in Stowe on the topic for health professionals.

He is also chair of a legislative advisory group that is considering whether Vermont should allow supervised medical use of psilocybin, a hallucinogenic substance found in mushrooms that is illegal in Vermont. The group will submit its recommendations to lawmakers in November.

"It's just a matter of time," said Barnett, who cofounded the 200-member Psychedelic Society of Vermont in 2021. "People believe in science, and that's why more mainstream people are opening their eyes to the possibility that these drugs aren't just from the 1960s for people who just want to trip."

Psychedelic mushrooms, including several species of fungi that contain psilocybin, have been used for centuries in therapy and recreation. In the past few decades, they've drawn the attention of mainstream health care providers and patients seeking relief from anxiety, depression and other conditions.

Many people have recently discovered psychedelics' potential through books such as Michael Pollan's How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, a No. 1 New York Times bestseller that's now a Netflix documentary.

Psilocybin is the most popular hallucinogenic in the U.S., according to the Rand Corporation, which surveyed adults this year. About 12 percent of respondents said they'd used psilocybin at some point in their lives, according to Rand, which estimated 8 million American adults used it in 2023.

That same year, there were more than 3 million Google searches related to microdosing, or taking very small amounts of a psychedelic, according to a study by the University of California San Diego. That's a twelvefold increase from 2015, the study found.

Skeptics, including the American Psychiatric Association, say more research is needed.

"Clinical treatments should be determined by scientific evidence ... and not by ballot initiatives or popular opinion," the group maintains.

If used judiciously, psychedelics can ease anxiety and depression and help PTSD sufferers resolve long-lingering traumas, proponents say.

"People can have epiphanies, a chance to rewire," said Lauren Alderfer of Brattleboro, a longtime psychedelic therapy advocate who studied in Holland to become a certified microdosing coach. She published a book called Mindful Microdosing earlier this year. "People's sleep is better; it makes our system more harmonious in a way that [conventional] medicines don't."

Alderfer added that taking microdoses herself has helped her care for her husband, who has early-stage Alzheimer's.

"As a caregiver, I have been so much nicer and kinder and have so much more tolerance," she said. "I definitely have more ease in how I live my life now."

Barnett used psychedelics recreationally when he was younger and attributes some of his personal and professional success to the lessons he learned from those sessions. He's been an advocate ever since, testifying in the Vermont legislature and doing interviews with local media. In his practice, he offers therapy with ketamine, a "dissociative anesthetic" that's approved for treating depression and other conditions.

Though he is frustrated by the slow pace of the psychedelics conversation, he's also gratified the drugs are attracting mainstream interest.

- Courtesy

- Items claiming to be Magic Mushroom gummies at a convenience store in Essex

Many people already grow, share and sell psychedelic mushrooms in Vermont, creating an underground economy that some hope to legitimize. The use, sale and possession of psilocybin is, like cannabis, still barred under federal law. Unlike cannabis, psilocybin use is still illegal under Vermont law.

Proponents and makers of the psychedelic MDMA, also known as ecstasy, suffered a setback in August when an advisory committee within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration rejected the synthetic drug as a treatment for mental health conditions.

That blow slowed the momentum of psychedelic acceptance, Barnett said. He thinks that's why only 100 people registered to attend his conference this year, after 230 turned out for it a year ago. Ultimately, he expects MDMA to win approval from the feds. But it might take a few years.

"It's frustrating," he said.

Last year, a bill to decriminalize psychedelics had 30 sponsors in the state legislature but stalled in committee. Lawmakers opted to create the working group to look at psychedelic-assisted therapy, a seasoned concept that has spawned a few dozen programs — most in California — that certify would-be psychedelic therapists, or guides. Oregon began allowing psychedelic-assisted therapy in 2023, and Colorado will begin accepting applications for licenses at the end of this year. The University of Vermont offered a course on psychedelic therapy over the summer as part of its continuing education offerings in the counseling program.

The Vermont committee has been taking testimony from experts, including regulators and practitioners in Oregon, as it prepares recommendations for lawmakers.

Oregon's law has resulted in a haphazard system that decides which patients are eligible for psychedelic treatment. Clinics must prescreen clients. They can turn away those who are deemed ineligible because they have taken the mood-stabilizer drug lithium in the previous 30 days, have thoughts of harming themselves or others, or have active psychosis, according to Angela Albee, who manages the psilocybin program at the Oregon Health Authority. But the process is not considered a medical or clinical model, so discretion is left up to the practitioner.

Heidi Venture, who co-owns Vital Reset Oregon, a licensed psychedelic therapy service center, described a process that was highly variable.

"I have one facilitator who won't screen anybody out," she said in testimony to the Vermont working group. "I have facilitators who it's hard to get them to screen people in."

Vermont Health Commissioner Mark Levine, a member of the working group, declined to discuss psychedelic therapy with Seven Days after the group's September 1 meeting.

"We don't really have data that gives us some sense of what the program's impact has been overall," he said during the meeting, after the Oregon program was discussed. "We insist on an evaluative process to make sure this fairly novel strategy would be really well researched and understood."

The Vermont Medical Society isn't taking a position on psychedelics, said executive director Jessa Barnard, who is also in the working group. She noted in an interview that Oregon's process sounds expensive and cumbersome; the drug must be administered by a trained guide in an approved setting and must be part of a talk therapy regime.

"It's a very complicated issue," Barnard said. "Some of the states took years to parse through these issues."

- Anne Wallace Allen ©️ Seven Days

- Shayne Lynn

To Shayne Lynn, a veteran of Vermont's young cannabis industry, local policy makers are dragging their feet unnecessarily, and that's putting potential psychedelic sellers at a competitive disadvantage. Massachusetts voters will decide whether the state should legalize limited psychedelic therapy and home use via referendum on November 5, he noted, and he thinks other Northeastern states will soon follow suit. Lynn's Burlington cannabis store, Lucky You, sells a kit that helps determine the psilocybin dose in homegrown mushrooms.

"I'd like to see the state embrace it and set up a program where you'd be able to go to a licensed store and purchase a microdose or purchase mushrooms," Lynn said. "I don't think it needs to be any more complicated than that."

Lynn and Barnett have an ally of sorts in Bob Gramling, a palliative medicine physician at the University of Vermont Medical Center who has been studying psychedelic therapy for years.

"As a palliative care physician, I've been paying attention to the growing science and have an expectation that this can have a profound impact in my field and for people who are seriously ill and dying," Gramling said.

He's in the working group, too, but doesn't intend to push for any particular action.

"I come to this with humility," he said. "My agenda is to understand its strengths and weaknesses and when it can be applied, in whom, and how."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.