- Benjamin Deflorio

- Al and Debbie Wood with a photo of their daughter Naomi

On May 19, 2020, Debbie and Al Wood were sitting around a campfire in the front yard of their Barnard home, enjoying a belated Mother's Day celebration with four of their grown children, when Debbie's phone rang.

The call was from Lakeland Girls Academy, a boarding school in Florida that their 17-year-old daughter, Naomi, had been attending for three and a half months. A staff member on the other end told Debbie that Naomi had been found unresponsive in her dorm room. She was being taken by ambulance to the hospital. Debbie and Al, devout Christians, made a circle with their three sons and daughter and prayed that everything would be OK.

Forty-five minutes later, Debbie's phone rang again. The school's codirector, Dan Williams, was telling her something.

"No!" Debbie screamed. "No! No! No!"

She collapsed to her knees, then sprinted to the house and into a bathroom. The family followed her inside and gathered by the closed door. Debbie emerged, still on the phone. "I don't know what they're saying," she told the others. "They're saying that Naomi is dead."

She handed the phone to her oldest son, Nehemiah, and collapsed again, sobbing. Williams repeated what he had told Debbie: Naomi had passed away. The cause was unclear. Williams offered his condolences.

- Courtesy

- Naomi with Nehemiah

For more than a year, as the Woods mourned Naomi's death, they took solace in their belief that Lakeland Girls Academy — and its faith-based parent organization, Adult & Teen Challenge USA — had done everything they could to help Naomi in that moment. Al even thanked them publicly on the website of his maple syrup business.

But last year, the Woods' lives were upended again by another piece of news, almost as shocking as the first. A report by the Florida Department of Children and Families concluded that Naomi's death was due in part to inadequate supervision and medical neglect by Lakeland Girls Academy, which billed itself as a therapeutic boarding school for troubled teens.

Now, the Woods find themselves navigating a parental nightmare that has required them to piece together the facts of their daughter's death with only shards of information. From their sorrow has sprung indignation. They have learned about allegations of abuse and neglect at similar schools and have seen firsthand how organizations such as Teen Challenge seek to keep disputes outside of the legal system through a process known as religious arbitration. These findings have thrust the Wood family into a campaign to seek justice for their daughter in the halls of Congress and through a lawsuit in the Florida courts, with a key hearing scheduled for later this month.

On a personal level, the Woods want a public acknowledgment from Teen Challenge that the organization had culpability in their daughter's death. They also want to ensure that no other family that sends a child to a residential center has to face the anguish they have.

"There is no hiding on our part or hiding on their part," Al Wood said of a wrongful death lawsuit that the family has filed against Teen Challenge, which operates more than 200 residential centers across the country. "We're going to see this process through, to tell the story ... and to see real change happen, at least with Teen Challenge. That's our hope."

'The Frequency Was Off'

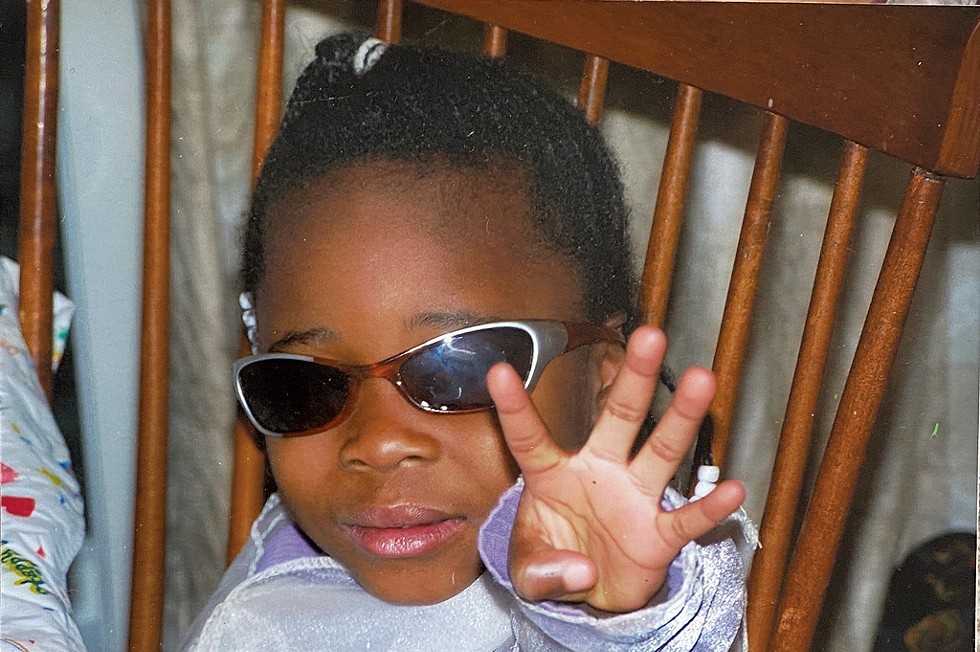

- Courtesy

- Naomi Wood as a child

The Woods live in a raised ranch on five grassy acres at the end of a gravel road in Barnard. There's an RV out front, and colorful Christmas lights adorn an attached shed, even in July. Their home is a few miles from the Barnard General Store, where, in summer, customers sit on the long wooden porch, eating ice cream cones and looking out at serene Silver Lake. Al's grandparents built the family home in the 1970s and sold it to him and Debbie for a song almost two decades ago.

The Woods are just an 18-minute drive from the tony enclave of Woodstock, where the family attends services at the First Congregational Church, a stately 19th-century building with a bell tower and Tiffany stained glass windows. Just 25 minutes away is Wood's Vermont Syrup in Randolph, where Al's family has worked the land for more than a century.

Al and Debbie met at a Christian college outside Boston and had three kids — Nehemiah, Jackson and Christian — in quick succession. They initially thought their family was complete but felt the tug of wanting to provide a home to other children who needed one. In 2005, Debbie and her sister traveled to an orphanage in Liberia, where they met and adopted 2-year-old Naomi and Zoe, just a year old. When the girls arrived in Barnard, Nehemiah, then 7, remembers his little sisters' eyes, wide and curious as they took in their new surroundings. All five kids slept on the floor together that first night. Two years later, the family rounded out its ranks when Bill, who was 9 and also of Liberian descent, joined through a domestic adoption.

In predominantly white, rural Vermont, the Wood family — with its half dozen children, three of whom were Black — were hard to miss. The kids grew up learning to swim at the lake, helping Al with the maple sugaring operation and taking summer trips to Acadia National Park in Maine.

Naomi was boisterous and giggly. Debbie remembers her and Zoe wearing tutus on their heads like veils and goofing off in the yard with their brother Christian and the family's Saint Bernard, Daisy. Naomi played soccer for a while in elementary school but preferred singing and dancing on the sidelines.

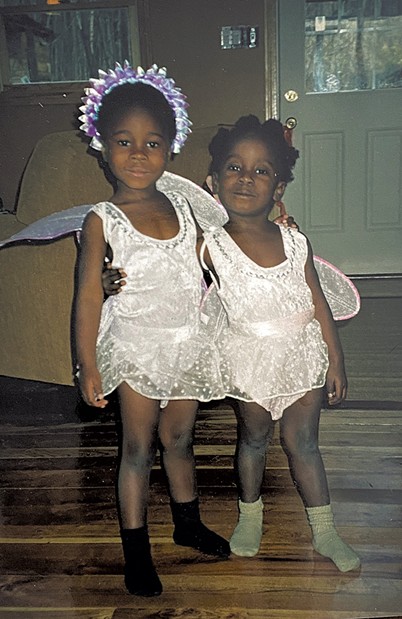

- Courtesy

- Toddlers Naomi (left) and Zoe

Naomi and Zoe, just a year younger, were close and even shared a bedroom. But as they grew older, their differences became more pronounced and their interests diverged, inserting what Zoe described as "a splinter" in their relationship.

Debbie and Naomi clashed regularly, too.

"I never quite felt like I was doing it right with her," Debbie said. "I was missing the signal. The frequency was off."

Debbie joined several adoption support groups and sought the help of the nonprofit Easterseals Vermont, which provides family coaching. Naomi spent the bulk of her middle school years at Kurn Hattin Homes for Children, a residential program in Westminster that was recently investigated by the state over allegations of abuse dating back to the 1940s. When Naomi returned to Barnard as a teenager, the atmosphere in the house grew more tense, Debbie and Al recalled.

Naomi got caught stealing a White Claw Hard Seltzer from the Barnard General Store, where she worked. She lied to her parents about having people over to the house and about having driven an old Volvo that wasn't street legal. While speeding on their gravel road one night in 2019, Naomi flipped her car into a ditch and had to be pulled out by a neighbor. That was the final straw for Debbie and Al. They believed Naomi was no longer safe at home.

Online research brought Debbie to the website of Lakeland Girls Academy. The program was run by Adult & Teen Challenge USA, an organization affiliated with the Pentecostal Assemblies of God church that, for more than 60 years, has operated drug and alcohol recovery centers for men and women, as well as schools for struggling teens. In 2006, then-president George W. Bush called it "one of the really successful programs in America."

The facility was part of a so-called "troubled teen" industry — a network of thousands of boarding schools, residential treatment facilities, wilderness programs and boot camps that serve approximately 50,000 adolescents nationally each year. There is no federal oversight of these programs, and allegations of wrongdoing are rife. Testimonials by self-described survivors posted on the website of the Unsilenced Project — a nonprofit that seeks to stop institutional child abuse — outline physical and psychological abuse, medical neglect, humiliating punishment, and religious indoctrination.

Teen Challenge has been accused of these practices in the news media — including a lengthy exposé in the New Yorker in October — and through informal, pop music-laden TikTok videos from teens who attended its programs.

For its part, Teen Challenge has been mostly tight-lipped about the accusations, but the organization issued a response to the New Yorker article last year, asserting that it could not comment on the cases mentioned in the article "due to privacy laws."

"We unashamedly affirm that we are a Christian nonprofit driven by the belief that a relationship with Jesus Christ will lead to radical life transformation," Teen Challenge said at the time. "This conviction, combined with other evidence-based support systems and structures, leads to success in the lives of those who graduate from our program."

Al learned about Teen Challenge while growing up in Randolph. In Vermont, the organization runs separate homes in Johnson for men and women with substance-use issues, as well as a facility for adults that offers meals and transitional housing in Rutland. In church, Al listened as men who said they'd been rehabilitated by the program gave testimonials. His family even housed some of them from time to time.

Over the last decade, the Vermont Attorney General's Office has received a handful of complaints about Adult & Teen Challenge Vermont's programs — ranging from questions about their efficacy to concerns that participants were flouting COVID-19 protocols. In a string of emails last year, a neighbor of one facility urged state and local officials to investigate after he found a T-shirt-and-shorts-clad adult client stranded on the side of the road on a 30-degree day.

But neither Debbie nor Al knew of the allegations of wrongdoing against the organization, some of which only came out after Naomi died. When Debbie mentioned Lakeland Girls Academy's affiliation with Teen Challenge, "it gave me a general sense of peace," Al recalled. "If she's going to go somewhere, at least I know it's safe."

Debbie traveled to Florida to visit the school and thought it would be a good fit, with staff members who seemed kind and promises of horse therapy and in-person family counseling sessions every other month. An older son was attending college in Florida, and the Woods thought they'd be able to visit both children during trips south.

Tuition at Lakeland Girls Academy was $4,300 per month. The Woods cobbled together money from church donations and Debbie's part-time job cleaning houses, and Teen Challenge offered a scholarship to cover the remainder. Debbie and Al hoped it would be the reset their family so desperately needed.

'Have You Seen the TikTok?'

- Daria Bishop

- Nehemiah Wood

Debbie accompanied Naomi to Lakeland Girls Academy on February 4, 2020, and signed a packet of paperwork prior to drop-off. One of those forms was called a Christian Conciliation and Arbitration Agreement. It stated that any dispute stemming from Naomi's stay at Lakeland would be settled by a Bible-based mediation process or, if necessary, arbitration in accordance with the rules of procedure for Christian conciliation — a legally binding, faith-based method for resolving conflicts.

"Oh, yeah, if she falls down, of course I'm not going to blame you guys," Debbie recalled thinking.

During her three and a half months at Lakeland, Naomi made use of supervised, 20-minute phone calls with her parents every other week, as school rules dictated. Her voice was mostly light and happy, Debbie said, and she seemed to like her teacher there. The COVID-19 pandemic hit hard a little over a month after Naomi enrolled, postponing the family's visit to Florida for counseling, but Al and Debbie felt confident that their daughter was in good hands.

On April 15, a staff member emailed Debbie to let her know Naomi had been suffering stomach pains and to ask whether she knew why or could suggest anything that might help. At the time, Debbie said, she didn't sense any cause for alarm, and the school never mentioned any health issues again.

Then, just over a month later, came the phone calls that Naomi had been unresponsive, then died. Later that night, the Polk County Sheriff's Office contacted the family to explain there would be an investigation. And then, after midnight, the agency that handled organ donations called. Al and Debbie were unaware that Naomi had marked on her driver's license that she wanted to be a donor. The person on the other end walked the Woods through the list of body parts they wanted to harvest: eyes, bone, skin, heart valves. The conversation was hard to bear, Al said.

The family traveled to Florida a week later to meet with Lakeland staff members and to collect Naomi's belongings.

- Courtesy

- Debbie with Naomi (center) and Zoe

In the room where Naomi lived and died, Williams, the center's codirector, gestured to a top bunk and told the Woods that it was where Naomi was found unresponsive. The family spent a few minutes taking in the space as a way of honoring it, recalled her brother Nehemiah, now 25.

The autopsy report, written by the Polk County medical examiner, came six months later. Al and Debbie were confused by one of its findings: Naomi had died of a seizure disorder.

Naomi had experienced seizure-like incidents on two occasions in 2018 — one after exposure to strobe lighting at a haunted house and another at school. But a neurologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center had determined that Naomi did not have any underlying condition, such as epilepsy, that caused seizures.

Still, Al said, he believed that the Lakeland school had done everything in its power to protect Naomi, and an investigation by the Polk County Sheriff's Office produced no criminal charges. Around that time, Al posted his message on Wood's Vermont Syrup's website explaining to customers that Naomi had unexpectedly passed away and thanking the Lakeland school for taking care of her.

In Florida, Christian-based residential care homes such as Lakeland Girls Academy are overseen by an independent authority known as the Florida Association of Christian Child Caring Agencies, rather than by the state's Department of Children and Families. But because Naomi had died in one of the facilities, DCF opened its own investigation.

Nehemiah was mid-shift at his job as a cook in New York City in July last year when he received a jarring Facebook message.

"Have you seen the TikTok that's blowing up about the DCF report about your sister?" the message asked.

Nehemiah finished his shift, his body shaking. When he arrived home, he read the full report, written by the Florida Child Protection Team's medical director, Dr. Carol Lilly.

It said Naomi had asked to see a doctor for chronic stomach pain in April, a month before her death. The center denied her request and never consulted with a physician about Naomi's medical issues. Instead, the report said, staff members gave her Pepto-Bismol. She received the over-the-counter medication approximately 20 times during her stay, according to the report. On the evening of May 18, Naomi's symptoms intensified. She vomited repeatedly throughout the night and the following day.

"Staff members made the child get up for meals and fed her soup, as that is their protocol," the report said. "They also prayed for her to get better."

- Courtesy

- Al with toddler Naomi

Only when Naomi was found unresponsive in her room at 6:15 p.m. on May 19 did anyone on staff call 911 and perform CPR. Emergency medical services transported her to Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center. She was pronounced dead at 7:16 p.m.

The report concluded that inadequate supervision and medical neglect by Lakeland Girls Academy contributed to Naomi's death.

It also contained scathing observations about the way the school operated. At the time of Naomi's death, Lakeland had no protocols for evaluating symptoms of illness or when to bring teens to the doctor or urgent care. Additionally, there was no documentation that Naomi was receiving any mental health services, the report stated. The center employed a practice it called shunning — in essence, prohibiting girls from speaking to one another — as a form of punishment. Dr. Lilly, the report's author, said that practice was likely to cause harm.

Nehemiah was struck by a seemingly small detail. The report noted that as Naomi was throwing up the night before her death, her roommates had moved her mattress from the top bunk to the floor to make her more comfortable.

But Nehemiah remembered the family's visit to Lakeland, when Williams, the center's codirector, had pointed to the top bunk, saying that was where Naomi had been found unresponsive. The discrepancy gnawed at Nehemiah: Was the school being as forthcoming about the circumstances of Naomi's death as the family had believed?

In Barnard, Debbie and Al — unaware that the DCF report even existed — started getting calls from Florida news outlets, asking for comment. The post on Al's business website praising Lakeland Girls Academy was still up. Hateful emails and phone messages started coming in.

"How could you do this?" "You sent her there to die." "You're terrible parents."

Al scrambled to take down the message.

Bound for Court

- Courtesy

- The Wood family

The Woods thought of themselves as the kind of people who put their faith in others to be honest and good, to own up when they'd done something wrong.

In that spirit, the family entered into a private mediation with Teen Challenge last fall, on the advice of their attorneys, with the hope that Teen Challenge would admit responsibility for what happened, apologize and commit to making its programs safer.

The Woods say they weren't interested in a payout in exchange for their silence. They wanted to be able to tell Naomi's story freely, not to settle quietly behind closed doors. The mediation broke down.

In January, Nehemiah obtained investigative notes from the Florida Department of Children and Families' probe that provided a clearer view into the mindset of Teen Challenge administrators.

In an interview shortly after Naomi's death, Teen Challenge's Southeast regional president and CEO, Brice Maddock, told Florida investigators that Williams and his wife, Holly, had done a "phenomenal job" as directors of Lakeland Girls Academy, and that Teen Challenge "stand[s] behind them." According to the notes, Maddock said Teen Challenge was going to "look at the situation and see what they need to do to avoid anything like this in the future" and "how to take precautions on how to protect [them]selves and more importantly protect the children."

In an interview in February 2021 that was also part of Florida DCF's file, Williams told investigators that the school had changed some of its protocols in response to Naomi's death. A newly added position of medical coordinator would now assess students' medical records and document treatment, and the school would begin checking the medical history of prospective students before admitting them, Williams said. The school would have to dismiss any student who needed mental health support, because it didn't have "the capacity or resources" to provide those services, Williams told investigators.

But in March of this year, Lakeland Girls Academy closed abruptly. A human resources director for the organization told a Florida newspaper that Teen Challenge was planning to open another school in a different part of the state, saying Lakeland hadn't been an ideal location.

Yet former students and staff told local media outlets that enrollment had dwindled since Naomi's death. Some former residents spoke out about school practices they deemed problematic: being required to remain silent around new students, having to write lines of Scripture hundreds of times when they broke a rule, not receiving the counseling services that were promised and being ignored when they complained of medical issues.

On April 27, the Woods filed a wrongful death lawsuit in civil court in Polk County against Dan and Holly Williams, Teen Challenge of Florida, and Adult & Teen Challenge USA.

"The lawsuit is really around a simple concept," Al said. "That Naomi needed medical care, and they did not provide that in a timely manner, nor did they have systems in place to guide them through that."

- Courtesy

- The Wood family in an undated family photo

The Woods are seeking damages and an acknowledgment by Teen Challenge that it was at fault.

"They're a Christian organization. We, obviously, are Christian people. So, our thinking is, if you do something wrong, you're supposed to own up to it," Al said.

But the Woods' path forward is not clear.

At the end of June, Teen Challenge filed a motion to dismiss court proceedings. The organization argued that the Woods agreed, by the paperwork they had signed before dropping off Naomi, to arbitrate any disputes through Christian conciliation, not in court. That method for resolving conflict — typically used by religious schools, churches and companies — takes federal, state and local law into account but uses the Bible as "the supreme authority governing every aspect of the conciliation process," according to guidelines published by the Institute for Christian Conciliation, a body overseeing such proceedings.

"Both Florida and federal law favor arbitration, with Florida courts holding that any doubt regarding the arbitrability of a claim should be resolved in favor of arbitration," Teen Challenge's motion asserts. It cites a 2008 Florida case in which a former employee of Teen Challenge sued the organization for failing to pay overtime wages, as well as a 2013 wrongful-death lawsuit in which a young adult who had been enrolled in a Teen Challenge substance-use program in Florida died of a drug overdose after being discharged. In both cases, Florida courts granted Teen Challenge's motions to compel religious arbitration.

But the Woods and their lawyers believe that the particulars of their situation — that Naomi died while living at Lakeland Girls Academy, as well as the state's findings that the school's medical neglect contributed to her death — make their case different.

When contacted by Seven Days, lawyers for Teen Challenge declined to comment, citing the pending litigation.

A hearing in Polk County civil court is set for September 21, when a judge will consider whether the Woods' case can move forward in court or be dismissed in favor of Christian conciliation. If the matter goes to conciliation, both parties can still be represented by lawyers, but a so-called "certified Christian conciliator" — often a practicing lawyer trained in the process — would stand in for a judge. Another key difference: Proceedings would be private, shielding Teen Challenge from additional public scrutiny.

Unlikely Activists

- Courtesy

- Jackson, Al, Debbie and Nehemiah Wood with Paris Hilton (center) in D.C.

Regardless of what unfolds on the legal front, Nehemiah is determined to shed light on Teen Challenge's practices. He's reached out to Lakeland Girls Academy staff, former students and their parents to gain insight into what happened to his sister. He also has spoken with staff members from other Teen Challenge programs, a New Jersey lawyer who has successfully sued residential programs for teens and a Michigan judge who is passionate about exposing child abuse.

- Courtesy

- Debbie and Nehemiah Wood in Washington, D.C.

"Teen Challenge for me — I grew up trusting it," Nehemiah said. But hearing others' stories has "sort of fortified my ability to be like, 'OK, mistreatment happens in these schools.'"

Just one semester short of finishing an undergraduate degree, Nehemiah, who moved to Winooski this year to be closer to family, hopes to finish college at the University of Vermont, then attend law school, with the aim of helping to reform the troubled teen industry one day. Until then, he believes that sharing his family's story is a way to advocate for policy change.

In May, two weeks after the Woods filed their lawsuit, Nehemiah traveled to Washington, D.C., with his parents and younger brother, Jackson, to lobby for proposed federal legislation known as the Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act. It would strengthen protections for young people living in congregate-care settings, such as residential treatment centers and therapeutic boarding schools. Similar legislation has failed to gain traction in Congress multiple times over the past decade.

- Courtesy

- A candlelight vigil in D.C.

The Woods met with Democratic and Republican lawmakers, spoke at a press conference, and chatted with celebrity heiress Paris Hilton, who has spoken out about abuse she experienced at a residential program in Utah. They gathered for a nighttime vigil with others whose lives had been changed by the troubled teen industry, holding candles in the dark.

During the vigil, Al recalled saying goodbye to Naomi in a McDonald's parking lot, between shifts at the sugarhouse.

"The next time I saw her, she was at a funeral home — dead," he said. "My wife was able to touch her. I could not bring myself to do that." After Naomi was cremated, "we brought her home in a backpack," Al told the group. "Change needs to happen so we can have a safer place for kids to go."

"To Naomi," attendees said in unison, raising their candles.

- Courtesy

- Debbie and Nehemiah Wood in Washington, D.C.

Zoe is still grappling with the loss of her sister. In the year following Naomi's death, she struggled to get through her days at Woodstock Union High School, spending much of her time speaking with counselors or in the nurse's office. Now a first-year student at Florida Atlantic University, Zoe said part of the reason she chose to go to college there was to feel closer to Naomi.

"I think being down here, it just means something more — to feel the energy," Zoe said. "It warms my heart."

Debbie and Al believe that Naomi is safe in the hands of God and that they will see her again. Still, that makes her death no less wrenching, even more than two years later.

Last month, the couple sat together on a couch in their compact living room, below a framed grid of images of their children when they were little. In the kitchen, a concrete island that they cast themselves was inlaid with shiny stones, fossilized rocks and six pennies — one from each of their children's birth years.

- Courtesy

- A press conference in D.C

Holding hands, the couple reminisced about their daughter and their hopes for her, now lost. Naomi loved to give hugs, but not typical ones. She'd walk up and just rest her head on your chest. She went through food phases. "Dad, I'm going to become a pescatarian," Al recalled her saying. "But I'm gonna start tomorrow, because tonight's meal looks really good."

Before leaving for Lakeland, Naomi attended an art and design program at the regional tech center. The family had talked about her going out to California after graduation to live near Debbie's sister, a photographer.

Debbie and Al have thought a lot about what they might have done differently.

"In hindsight, we never would have sent her there," Al said.

Debbie still views the time before Naomi went to Lakeland Girls Academy as a rough patch, a chapter in what should have been a longer story. If things had turned out differently, she and Naomi might have emerged on the other side stronger and more understanding of each other.

Instead, Debbie said, "we never got to see the end of this chapter."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.