- Alphaspirit | Dreamstime.com

If you're a parent with school-aged kids, chances are you've heard the term "proficiency-based learning." It's a hot topic, and for good reason: Vermont's Education Quality Standards, adopted by the State Board of Education in 2013 and implemented the following spring, call for all high schools to use proficiency-based graduation requirements by the time the current class of seniors graduates, in June.

While the rollout has gone relatively smoothly in some schools, the confusion and pushback in others have sent ripples all the way to the Statehouse. In some school districts, parents have voiced concern that new, lengthy transcripts are confusing and will hurt their children's college acceptance chances. One principal abruptly resigned amid such a controversy at his high school. Another school recalculated GPAs while students were in the midst of applying to colleges. A 2019 survey of 1,000 Vermont-National Education Association members found that more than half of them did not think they received adequate resources to make the transition to a proficiency-based learning system.

The state has now backpedaled on the deadline, and a group of legislators has moved to make the whole system optional. When the State Board met in January to hear testimony about the proficiency-based learning approach, the meeting lasted seven hours.

One Vermont private high school has capitalized on the uncertainty by marketing itself to prospective parents and students with a simple question: Tired of proficiency?

What follows is our attempt to unpack the proficiency paradigm and explain how Vermont came to adopt it. We'll show you what it looks like at Champlain Valley Union High School, which began implementing the approach more than a decade ago, years before the state required schools to do so.

What Vermont Requires

In short, a Vermont student needs to demonstrate proficiency in the seven curriculum areas the state requires — and complete any other requirements their school district sets — in order to graduate. Passing an exam is just one way for students to demonstrate proficiency. Others include creating a portfolio, performance or project.

The state leaves implementation details to local school districts and supervisory unions. Beyond requiring them to provide appropriate, personalized learning opportunities — both in and out of school — designed to ensure that all students can meet graduation requirements, state standards don't spell out what teaching or grading should look like.

Some schools have made major changes to their approach to adopt proficiency-based learning, which is also known as standards-based, competency-based and mastery-based learning. The Vermont Agency of Education offers a lengthy definition online: "Proficiency-based Learning is any system of academic instruction, assessment, and reporting that is based on learners demonstrating proficiency in knowledge, skills, and abilities they are expected to learn before progressing to the next level or challenge."

Mike McRaith, assistant director of the Vermont Principals' Association and former principal of Montpelier High School, puts it in simpler terms: "Proficiency-based learning is a well-established framework for schools to help answer two basic questions: 'What will students learn?' and 'How will we know they have learned it?'"

As the deadline to implement proficiency-based graduation requirements looms, questions remain about its future in Vermont.

Publicly, Vermont Secretary of Education Dan French has stated that the 2020 implementation deadline is not a "hard-and-fast date." Ted Fisher, director of communications and legislative affairs for the Agency of Education, clarified French's position in a February email. "Secretary French would like to see school boards and supervisory unions successfully implement strong proficiency-based systems. Doing this well takes time," he wrote. Though the Agency of Education does not plan to ask the State Board of Education to change the Education Quality Standards, Fisher continued, "districts who take more time to implement a strong system are not out of compliance."

Earlier this year, four state legislators introduced a bill, H.665, to make proficiency-based learning and proficiency-based graduation requirements voluntary. Rep. Heidi Scheuermann (R-Stowe), the lead sponsor of the bill, said she introduced it because of the confusion and challenges implementation has caused. The Agency of Education has given "very little direction" to school districts in terms of how proficiency-based learning should be implemented, she added, and the initiative could undermine Vermont's good reputation for educational quality.

Some point to Maine as a cautionary tale. In 2012, that state passed a law requiring the class of 2021 to demonstrate proficiency in eight different subject areas in order to graduate high school. The initiative was "plagued by insufficient funding and inadequate guidance from the top," according to the Hechinger Report, and the law was repealed in 2018.

In January, the Vermont State Board of Education held a marathon seven-hour meeting at Rutland High School in which educators, students and parents gave testimony about proficiency-based learning. Many speakers touted its benefits — from the clarity that specific learning targets give teachers and students to the more collaborative environment created in classrooms — and urged the state to stay the course. Others labeled it confusing and demotivating to students and lamented the lack of data on its effectiveness.

It's possible that both sides are right. In Vermont, schools are locally controlled, which means local school boards determine how to implement state education policy. Consequently, proficiency-based learning can look different from district to district. Vermont-NEA president Don Tinney emphasized this point to lawmakers last year. "Anyone would be hard-pressed to find any two school districts that have implemented this new approach in the same way," he said.

Proficiency in Action

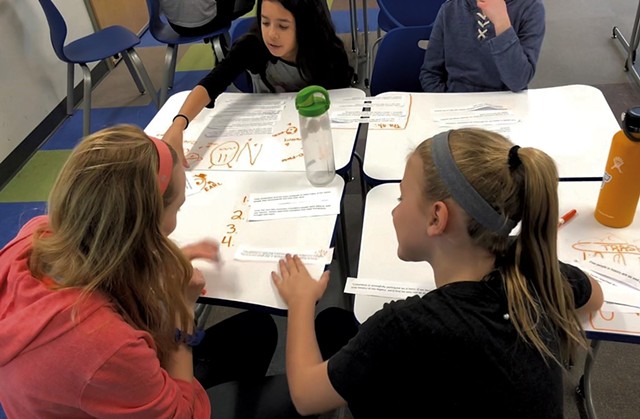

- Middle school students at Shelburne Community School work on the evidence learning target

Champlain Valley Union High School in Hinesburg began implementing proficiency-based learning before the most recent Education Quality Standards were adopted. In place for more than a decade, the system has become embedded in the way educators teach and students learn. A visit there provides a snapshot into what proficiency-based learning looks like after years of professional development, teacher collaboration and practice.

On a Monday morning in February, students in Katie Kuntz's ninth-grade humanities class are on week four of a six-week unit on world religions and religious conflicts. Prior to proficiency-based learning, students would likely have learned about the conflicts at the same pace and, at the end of the unit, taken a test to measure how well they could recall the content.

Now, the focus is on how well students can demonstrate specific skills using the course content, instead of just focusing on the content alone. Kuntz and her teaching partner, Katie Antos-Ketcham, have worked with the six other ninth-grade humanities teachers to develop a K-U-D chart for the yearlong course — specifying what they want students to know, understand and be able to do by June. Included in that chart are the topics they will study and literature they will use, as well as 12 learning targets — skills including critical thinking, making a claim and writing organization — that they want students to acquire. Each of those 12 targets has a four-point rubric, or learning scale, that explicitly states what students need to do to show proficiency. And each learning target is designed to provide evidence that students are meeting one of the school's 14 proficiency-based graduation standards.

All of CVU's learning targets are transferable, meaning they are skills that can be applied across courses and discipline areas. For example, making a claim and critical thinking are skills that students can use not just in humanities, but in science and life after high school, as well.

Kuntz and Antos-Ketcham, who have been teaching at CVU for more than 19 and 17 years, respectively, say that proficiency-based learning has changed their teaching practices for the better and made it easier to get to know their students as learners.

Kuntz says that thinking about what students should be able to know, understand and do by the end of a unit or course has given her teaching more focus and specificity. While the content she's teaching hasn't necessarily changed — students still read Homer's The Odyssey in freshman humanities, for example — she has had to be more precise about what she wants students to learn by engaging with the material.

In recent weeks, Kuntz's students have been working on the "evidence" learning target, which calls for students to use multiple relevant and specific pieces of evidence to develop a claim. Individually or in pairs, they've identified a religious conflict they want to study in more depth — from the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar to the long-running Israeli-Palestinian conflict — and begun their research. A note-taking chart provides students with a place to answer specific questions: Who are the major groups involved in the conflict? What are the reasons for the conflict? How have people tried to solve the conflict?

At the bottom of the chart, the learning scale for the evidence target states what students will have to do to achieve a 1, 2, 3 or 4, providing students with a clear pathway to achieve the learning target and giving teachers a rubric to evaluate students' work. By breaking down the curriculum into learning targets, teachers can pinpoint students' specific areas of weakness, then personalize instruction to help address individual needs.

Freshman Juliette Chant, who is studying India and Pakistan's conflict over the Kashmir region, says learning scales are helpful because they make it easy to know what she needs to do to meet or exceed each learning target.

On this recent Monday, Kuntz introduces two new learning targets related to communication — voice and physical expression — that students will need to demonstrate when they give presentations about their religious conflict in a few weeks. She shows them learning scales that state what a student must do to achieve a 1, 2, 3 or 4 in each of them.

In a Think Tank elective for 10th through 12th graders taught by Stan Williams and Emily Rinkema, students are tasked with identifying a problem or issue in the school, then designing a project to address it. This semester, students' projects range from making a mobile cart with yoga mats, adult coloring books and more items that students can use to mitigate stress, to organizing a breakfast club where students can discuss mental health issues, to creating a podcast for NPR's Student Podcast Challenge. As they work to implement their diverse projects, all students are being assessed on the same four learning targets — evaluation, synthesis, iterative process, and media production and use.

Under proficiency-based learning, assessments fall into two categories — formative and summative. Formative assessments are small, precise tasks teachers assign to help determine what instruction a student still needs to meet learning targets. These assessments also help students see their progress and don't count toward a final grade. Rather, they are designed to help students build the skills that will be more formally assessed, in the form of an essay, project, performance or exam, at the end of the unit — called a summative assessment.

In the ninth-grade humanities unit on world religion, for example, the conflict chart students have filled out will be used to assess the evidence target; a presentation on the conflict they have studied will assess the two communication targets; and a graphic organizer on the five major religions will address the critical thinking target. Scores on each of the learning targets are shown on an online portal called JumpRope, and a final grade for the course is a weighted average of a student's performance on all the learning targets for the class — with targets that have been assessed more frequently given more weight.

One point often raised by critics of proficiency-based learning is that the practice of reassessment, or allowing students to retake a summative assessment if they don't perform well, decreases students' work ethic and academic rigor. But at CVU, redos are rare. Freshman Kate Boget explained that in order to redo an assessment at CVU, students need to get a parent's signature, meet with a teacher to explain why they want to redo the assignment and, if they get approval, do the work again. She said she'd rather do well the first time than go through that process.

CVU senior and student body copresident Beckett Pintair said that while he believes proficiency-based learning still has room for improvement in terms of its implementation, he believes it has the potential to be "incredibly positive" for students. "PBL can give kids the chance to focus on the actual learning instead of what grade they will get for the class. This will change kids' mindsets and motivate kids to learn, rather than shutting them down, punishing them for what they don't know."

Set Up For Success

- Champlain Valley Union High School junior Maddie Evans with a "stress-free" cart she designed for her Think Tank elective

CVU is well equipped to implement proficiency-based learning for a number of reasons. It discovered the model years before the state mandated proficiency-based graduation requirements. Its teachers have had years of professional development on the subject. And the two educators who helped bring the model to the school — Williams and Rinkema — have written a book on the topic and now spend half of their time working as proficiency-based learning coordinators for the Champlain Valley School District, which, in addition to CVU, includes four K-8 schools in Shelburne, Williston, Hinesburg and Charlotte.

It really started out as a "grassroots initiative," CVU principal Adam Bunting said.

Twelve years ago, Williams and Rinkema were both on sabbatical from CVU when their research into differentiating courses and raising rigor for students led them to proficiency-based learning. Its method of establishing clear learning targets seemed to them to be the key to meeting the needs of all students. They brought back their findings and have spent the years since working with other educators at CVU, and now at the district's middle schools, to implement the method.

In 2019, their proficiency-based learning guide for educators, The Standards-Based Classroom: Make Learning the Goal, was published by Corwin Press.

Proficiency-based learning is more than an external mandate at CVU, Rinkema said. It has "staying power" and is part of the "long-term vision" of the district, she said.

CVU has deliberately made incremental changes. Though the methods for teaching and learning and the ways grades are calculated have changed, students' scores are converted to letter grades four times a year, and they still receive GPAs. Transcriptssent to colleges still look the same. At the state board meeting, Rinkema described this decision to hang on to what was familiar to families as "a bit of a compromise" the school made in order to have more freedom to change instructional and assessment practices. Bunting said he sees the current grading practice as a bridge to where CVU is hopefully headed — transcripts that reflect what students know and are able to do rather than just provide an aggregate grade. But, he said of the school's decision not to change the way transcripts look, "our sense was the community wasn't ready — yet."

Both Bellows Free Academy-St. Albans and U-32 are examples of schools that changed their student transcripts to reflect proficiencies and ran into trouble. In October, BFA principal Chris Mosca resigned after the school released several versions of student transcripts, some of which were cumbersome and difficult to understand. At U-32, student GPAs — which had been calculated using a proficiency-based grading scale — were recalculated in December after some larger, out-of-state universities requested a conversion chart to a traditional grading system.

For its part, the Agency of Education does not take a position on how school districts or supervisory union should structure their grading practices. Though the agency has provided school districts with resources on the topic, including a 2018 research brief on proficiency-based grading practices, "grading is a local decision," said Fisher.

A Plan for Collaboration?

When proficiency-based learning is not implemented with full fidelity or understanding, it won't work, Williams said. It's not a "program" that schools "can just plug in and have ready to go."

Implementation requires thoughtful planning and team effort, Williams and Rinkema say. Shifting to a model of teaching that challenges the way teachers have traditionally done things "is not going to go smoothly," they write in their book. "It's going to be messy and rocky and contentious and uncomfortable. You will get things wrong. You will make mistakes."

Williams stressed the importance of Vermont schools having common language around the tenets of proficiency-based learning, adding that a lack of common vocabulary makes sharing and collaborating a challenge. He also thinks the Agency of Education should act as a resource for schools that are having difficulty implementing proficiency-based learning, connecting educators struggling with specific aspects of the model with those who have had success.

"We have so much experience and so many resources to offer each other, but we don't have systems and structures in place to make this easy," Williams and Rinkema wrote in their prepared testimony for the State Board of Education meeting in January. "It's so important that we work together as a state to maintain fidelity to the simplicity of the foundational principles, while navigating the complexities of implementation."

Pat Fitzsimmons, the proficiency-based learning team leader at the Agency of Education, said the agency has provided professional learning opportunities and tools to help educators implement proficiency-based learning. And agency spokesperson Fisher said there is "a combined effort" of organizations such as the Vermont Principals' Association, the Vermont Superintendents Association and the Vermont Curriculum Leaders Association to support proficiency-based learning in the state.

CVU principal Bunting suggested the Agency of Education needs more funding to support the initiative. And, in turn, he said, the agency needs to provide more opportunities for educators around the state to collaborate to improve their practices.

As principal of a school that has worked for years to create a proficiency-based system, Bunting said that if Vermont were to abandon its move toward the model, it would send a bad message to educators, especially those who were early adopters and are making gains with students. It would also empower what Bunting calls the "really dangerous" type of thinking that all educational change is a pendulum, swinging in one direction for a few years and then back a few years later. Vermont has the opportunity to assume the "leadership mantle," when it comes to proficiency-based learning, he said. "I can't articulate strongly enough how disappointed I would be if our state backs off this."

— A.N.How We Got Here

Vermont officially adopted proficiency-based graduation requirements in late 2013. In December of that year, the State Board of Education approved new education standards that shifted the focus from input to outcomes, or, as the Agency of Education explains online, "from a focus on courses and Carnegie units (seat time) to a focus on mastery of content."

The Education Quality Standards require that the class of 2020 demonstrate proficiency in seven curriculum areas (see below) — and fufill any other requirements specified by their school district — in order to graduate.

The change stems from a state law — also adopted in 2013 — that requires schools to develop personal learning plans for students and to allow students to learn outside the classroom, including online, at a workplace, in a career or technical center, or in college. That law, Act 77, is called the "flexible pathways initiative." Students can take different paths to graduation, and yet their diplomas need to mean something, said Rebecca Holcombe, who was Vermont's secretary of education from January 2014 until April 2018. "So that's the logic of proficiency-based graduation [requirements]," Holcombe said. "If they're taking different roads, how do you know they're getting to the same place?"

Though this approach is new, the idea is rooted in educational theories the state has been discussing for years. The Agency of Education's website goes so far as to trace it to John Dewey, the academic philosopher — born in Burlington in 1859 — who believed that education should be based on the principle of learning through doing.

"Things sort of come around again and again," said Holcombe, now a Democratic candidate for governor. "I mean, nothing we're talking about now is something that people haven't tried to figure out how to tackle before."

Throughout the last two decades, the state has studied "flexible pathways" and proficiency-based graduation requirements. Laws have moved incrementally in that direction. Movement accelerated under governor Peter Shumlin, who made education reform a priority during his tenure from 2011 through 2016.

In his 2012 budget address, Shumlin said that the state's education system was too rigid to adequately serve diverse learners. "Flexibility is critical for all students," he said, calling for an expansion of school choice, allowing dual enrollment for high school juniors and seniors to take college courses for college credit and allowing students to enroll full time in college during their senior year.

The following year, Shumlin devoted his entire 2013 State of the State address to education, calling it "the state's greatest economic development tool ... If we stand by, if we fail to innovate, and if we refuse to change, we will slip behind..." he said. "The high school degree that brought success and a lifetime job in the old economy ensures a low-wage future in the tech economy." Sixty-two percent of job openings in the coming decade would require postsecondary education, Shumlin said, yet only about 45 percent of Vermont students who started ninth grade continued their education beyond high school.

Six months later, in July 2013 — in response to Shumlin's agenda and as a result of years of work by educators and policy makers — the legislature passed Act 77.

Neither the law nor state education standards specify how teaching should be carried out in schools or what report cards should look like. Local school districts make those decisions.

Krista Huling, a social studies teacher at South Burlington High School, was on the State Board of Education when the new standards were adopted. (She resigned in August to serve on Holcombe's campaign.) "I think how we got here was just, education leaders at the time really wanted more for their students," she said. With the world changing as fast as it is, teachers don't even know what kinds of jobs their students will get, so they need to prepare them to be creative thinkers, comfortable with technology, who can interact with each other, Huling said. "This idea [is] that we are trying to create a system that is more flexible for our students. So that way, they have more opportunities in the future, not less."

— M.A.L.The curriculum content state standards require:

- Literacy (including critical thinking, language, reading, speaking and listening, and writing)

- Mathematical content and practices (including numbers, operations, and the concepts of algebra and geometry by the end of grade 10)

- Scientific inquiry and content knowledge (including the concepts of life sciences, physical sciences, Earth and space sciences, and engineering design)

- Global citizenship (including the concepts of civics, economics, geography, world language, cultural studies and history)

- Physical education and health education

- Artistic expression (including visual, media and performing arts)

- Transferable skills (including communication, collaboration, creativity, innovation, inquiry, problem solving and the use of technology)

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.