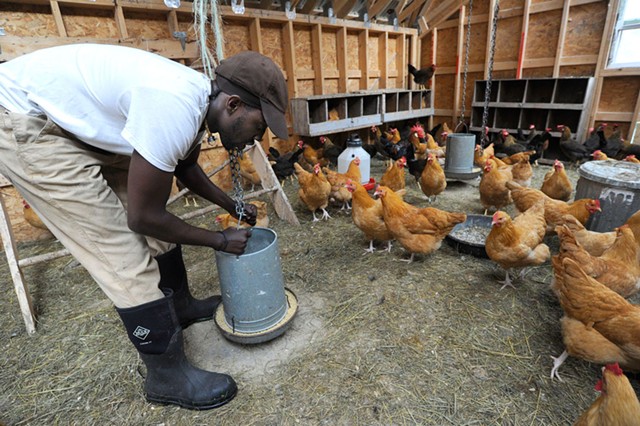

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Sterling College student Tofowa Pyle tends to chickens on the school's farm

Like most college students, Tofowa Pyle expects to pull an all-nighter or two before the end of the school year. But while students at most other colleges and universities burn the midnight oil writing term papers and cramming for exams, Pyle could be up until the wee hours tending to a pregnant sow or sick steer.

A senior at Sterling College in Craftsbury Common, Pyle will soon take over as work adviser to the crew of students that cares for the school's livestock. The sustainable-agriculture major was hired for the job in part because of his experience rearing farm animals in his native Guyana. To earn a bachelor's degree at Sterling, Pyle must hold a job on or near campus.

But tending to animals won't be his only work requirement this fall. Like all 130 students at this tiny private college in the Northeast Kingdom, Pyle is also required to work in the kitchen, clean dorms or perform other forms of menial labor that facilities staff or outside contractors would normally cover on other college campuses. Last semester, Pyle worked three mornings each week, from 6:30 to 8:30 a.m., making breakfast for fellow students and staff. He arranged his schedule so none of his classes started immediately afterward.

"Nobody complains about the work they have to do," he said. "Students here are all pretty chill."

Sterling College — whose official motto is "Working Hands. Working Minds." — is a federally recognized "work college," the only one in the Northeast and one of just seven in the United States. That means every student living on campus must hold a job, regardless of financial need. That workload is in addition to any need-based work-study assistance they might receive.

Sterling's students choose from a variety of jobs, such as tutoring schoolchildren at neighboring Craftsbury Academy, working in the college admissions office, supervising the campus' climbing wall or repairing mountain bikes. As in any workplace, competition can be fierce for the more desirable positions; those requiring higher levels of skill or responsibility also pay more.

But students' wages — every job guarantees a minimum pay of $1,650 per semester — aren't deposited into their checking accounts. They're credited toward tuition. As a result, Sterling College costs students 20 percent less than do other private New England colleges. Students' debt loads upon graduation are typically smaller, too — on average, $15,500 for a four-year degree, compared with the national average of $31,200.

In an era when so many college students struggle to make ends meet — and then spend years paying off tens of thousands of dollars in student loans — Sterling College is among a handful of colleges that have embraced a more economical model. Its policy reduces the overall cost of higher education, provides students with valuable life skills and résumé-building experiences, and levels the playing field for those of more modest backgrounds.

"Of course, it does help with the cost of education," said Sterling College president Matthew Derr of the work-college program. But he added that the program's benefits don't end with practical concerns: "It also means that students' entire college experience is colored by the opportunity to do meaningful work on campus and in the community."

The "work" in "work college" is readily apparent the moment one sets foot on Sterling's scenic, mountainous campus. Here, students are more likely to sport Carhartts and work boots than shorts and sandals, even on a humid August afternoon. On a recent visit, this reporter quickly spotted a female student toting a hard hat in one hand and a chain saw in the other. Just down the hill in the barn, a gaggle of students stood beside a draft horse and listened to a lesson on how to size a harness. In an adjacent outbuilding, a lone student raked out a chicken coop.

At Sterling, sustainability isn't just a trendy buzzword but a philosophy that is incorporated into every aspect of campus life. The college has been ranked No. 1 in the country two years in a row in the national Real Food Challenge, which means that most campus meals are produced locally, sustainably, humanely and through fair-trade practices. About one-fifth of the food served, including fruits, vegetables, meats, eggs and maple syrup, is grown or raised by students themselves.

And this fall, Sterling will cut the ribbon on 11 new solar trackers, which will enable the campus to meet nearly all of its electricity needs through renewable sources.

Sterling students tend to know what they're signing up for. As a small rural college with a heavy emphasis on environmental stewardship and outdoor recreation, the institution naturally attracts students who are accustomed to getting their hands dirty.

Emlyn Jones, a 28-year-old senior from a small farming community in northwestern Illinois, said he discovered Sterling through a Google search while he was on a six-month military deployment in Afghanistan in 2012. The GI Bill covers many of his college expenses; his campus jobs supply the rest.

Jones' campus employment has included work on a forestry crew, which focuses heavily on maple syrup production. In the fall, the crew prepares the sugarhouse, then harvests, splits and stacks firewood. When the sap starts running in the spring, Jones said, "We drill lots of little holes in trees."

Jones said he chose Sterling specifically for its work program, which offered him the opportunity to learn to run the 200-acre family farm his mother inherited six years ago.

"Coming here has really given me a good template on how to go about things," Jones explained. "I come from a farming family, but I feel like we're almost starting anew."

Other students arrive at Sterling knowing little about agriculture or the work program itself. Alice Haskins is a 21-year-old senior who will graduate in December with a double major in sustainable food systems and environmental humanities. She recalled that even her academic advisers at St. Johnsbury Academy had never heard of a work college.

"The work-college aspect of Sterling College is something I love, but it's not something I was specifically looking for," Haskins said. When she told her high school colleagues about the college, their opinions were mixed.

"Some of my friends went away to Ivy League schools and said, 'I don't want to do that. It sounds weird,'" she recalled. "But other people were really excited and thought it's a really cool model."

Sterling College was an early adopter of the work-college model, which was created by the federal government in the early 1990s. The college itself began as a boys' preparatory school in 1958. As prep schools declined in the mid-1970s, Sterling converted itself into a gap-year program offering classes in forestry management and sustainable agriculture, then into a two-year associate's degree program. In 1997, Sterling was accredited to issue four-year bachelor's degrees and became a work college. (Goddard College in Plainfield also operated as a work college from 1995 to 2002, when it discontinued its undergraduate residency program.)

Why haven't more colleges adopted the model? Robin Taffler is executive director of the Work Colleges Consortium, a Berea, Ky.-based nonprofit that represents the nation's work colleges. She explained that, while several other colleges are in the process of gaining federal recognition, it's a complex, costly and time-consuming process.

While the colleges in the consortium differ considerably in size and academic emphasis, Taffler said, they all share a long history of and commitment to hands-on, experiential learning.

"Our schools literally would not operate if our students didn't show up," she said. "They really run all essential functions at our colleges." All work colleges also share the small pie of federal funds that supports them.

Derr suggested there's something about the character of small work colleges and the students they attract that "might not work at a Big 10 university."

For instance, as students are required by law to devote a significant portion of their extracurricular hours to their jobs, they have little time for collegiate team sports. Instead, Sterling's students tend to participate in individual athletic pursuits such as Nordic skiing, rock climbing, trail running and mountain biking.

Running a work college also puts added burdens on faculty and staff, Derr acknowledged, as they serve as both educators and work supervisors who train and evaluate their "employees." Can students get fired if they don't show up or perform their work properly?

"Yeah, they can. And they do!" Derr said. But, he pointed out, that's part of the role of a college — to help students develop a sense of responsibility for their professional commitments.

"We understand the civic virtues that colleges are supposed to impart to their students," he said. "The work program is a means to achieve that."

It also imbues students with a deeper sense of responsibility toward the community at large, Derr added.

"Our students are much more respectful of the physical plant than anywhere I've ever been," the president said. "People don't necessarily come to college knowing how to use a mop. And they don't leave Sterling without knowing how."

All that manual labor doesn't just build muscles and character; it also builds résumés. According to the school's own alumni surveys, 95 percent of Sterling graduates report getting a job within one year of graduation, and 90 percent of those jobs are directly related to their majors.

What about the oft-touted "college experience"? Students insist that their work duties don't cut into their social lives but actually improve on them. Said Jones, "I personally connect with people better when we're working together."

The same seems to hold true for Sterling's staff. Executive chef Simeon Bittman, who cooks for 125 to 150 people per meal, confessed it can be challenging working with students who don't know their way around a kitchen. But it can be rewarding and fun, too, he noted.

"Working side by side with someone who has no experience is a good reminder of where we all started," Bittman said. "We all had teachers who taught us what we needed to know to keep moving forward — not just in the kitchen but anywhere in life."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.