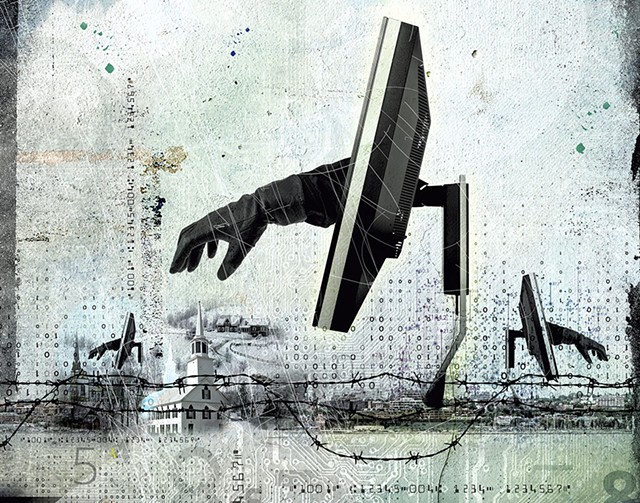

- David Junkin

Ernie Saunders was visiting Salem, Mass., in January 2018 when he learned that the software he's long supplied to nearly every Vermont town government was bewitched.

An email from a Vermont technology consultant delivered the bad news: Flaws in Saunders' accounting software had left taxpayers' bank information and municipal employees' Social Security numbers improperly exposed — and vulnerable to theft — for more than a decade.

Saunders, founder of the Vermont software company New England Municipal Resource Center, or NEMRC, agreed that the concerns were "legitimate" and later patched his product. But he didn't inform his clients about the specific vulnerabilities, which dated back to 2006. Why not? Concerns about data security, he believes, tend to be overblown. Besides, the bank routing and account numbers involved were "no more than what's on the bottom of a check."

"I went to the witch museum and realized what the whole definition of a witch hunt is," he recalled, comparing the public fixation on cybersecurity to the mass hysteria that led colonists to execute supposed witches in Salem. "And I don't put this in that category totally, but I think that it is, a little bit."

Then, last Thursday, a South Burlington-based company called simpleroute — the IT firm that first reported the bugs to Saunders — decided to disclose them itself on its website. The vulnerabilities raise questions about whether Vermont towns are equipped to safeguard sensitive data.

"I feel like people really deserve to know that this is an issue with this software," simpleroute president Brett Johnson said.

City and town officials contacted for this story were not aware of simpleroute's findings and had not seen its report. Even the Vermont League of Cities & Towns, which regularly hosts cybersecurity trainings and provides insurance coverage for members, did not know about the NEMRC vulnerabilities until contacted by a reporter last week, executive director Maura Carroll said.

While no data breaches have been reported to VCLT or the state attorney general, experts say they would be difficult or impossible for many towns to detect. What's more alarming, they say, is that until NEMRC's recent fixes, unencrypted personal data held by local governments was as little as three mouse-clicks away for anyone with access to a town's network.

"It's actually shocking to see that systems are handled this way," said Ali Hadi, an assistant professor in computer and digital forensics at Champlain College. Hadi worked in cybersecurity in Jordan before joining the college last year.

"I didn't think I would see this in the U.S., to be honest with you," he said.

NEMRC is nearly synonymous with municipal accounting in Vermont. Saunders started the company in 1986, two years after he wrote the state's first grand list program for the Town of Castleton. Since then, NEMRC has essentially cornered the software market for municipal bookkeeping, dog licensing, utility billing and more. All 255 municipalities in Vermont use at least one NEMRC module, according to Saunders, and about 190 use the payroll and tax administration software in which simpleroute found long-standing bugs.

NEMRC's software gained wide use in part because of its low cost. Saunders said one town saved more than $100,000 annually by ditching a Fortune 500 company's offerings in favor of his locally made software.

"I don't think you're going to find anyone in Vermont more concerned about the health of local government," Saunders said. "I've been able to save Vermont taxpayers a lot of money by not charging what these big companies charge."

The affordable systems run on older database software called Visual FoxPro 7, which was released in 2001. Microsoft discontinued technical support for the software years ago. Simpleroute's Johnson started looking into NEMRC once his firm picked up a couple of Vermont towns as IT clients. He said he reasoned that the advanced age of Visual FoxPro could be a sign of security problems and that it was worth investigating.

In December 2017, simpleroute programmers identified three vulnerabilities in the software.

Two of the problems potentially allowed users with access to a town's server to obtain unencrypted files containing Social Security and bank account numbers. Every time a town accountant ran a Form W-2 report for municipal employees, a second copy containing their Social Security numbers was created on the network's shared drive. While towns typically restrict access to the payroll application itself, they frequently extend shared drive access to many or all municipal employees, and sometimes to visitors and contractors, Johnson said.

Saunders had been aware of that problem, but rather than update the software, he'd made a point to remind attendees at NEMRC seminars to manually delete the file each time they ran a report.

"From a security standpoint, it's really not acceptable," Johnson said of NEMRC's previous reliance on manual deletion.

In the second case, simpleroute engineers were able to locate taxpayer bank routing and personal account numbers stored without encryption in a file that was also accessible through the shared drive. The earliest such file they located on one of their client servers was created in December 2006.

Only people with access to a town's local network — those with passwords — could have exploited these vulnerabilities. But another flaw could have enabled any third party to intercept data as towns uploaded it to an NEMRC backup system in the cloud.

"It's something that cities and towns need to take very seriously and make sure the data they're trying to protect is secure," said Jon Rajewski, director of Champlain College's Senator Leahy Center for Digital Investigation. The data contain personal information about Vermonters "that someone could use for a lot of evil," he added.

The security of all software relies, in part, on third parties who identify and report flaws. Apple, for example, credits those who report bugs in its products. A 14-year-old Arizona high schooler, Grant Thompson, discovered this month that a glitch in Apple's FaceTime app allowed users to remotely turn on people's microphones and eavesdrop on them. Apple, chagrined, publicly thanked him.

Reporting parties are expected to follow ethical rules for disclosing security holes, said Greg Schoppe, lead developer for Burlington web services company Bytes.co. They should notify the software creator first, then try to negotiate a time period for the problem to be fixed before it's publicly disclosed.

Schoppe has some experience with the process. In 2015, as a private citizen, he uncovered a security problem with an online bill-paying portal used by the Burlington Electric Department. Schoppe was able to hack his own password and deduced that the software was storing customer passwords without encrypting them.

He tried contacting the department but struggled to get the message to the right person. So he posted his findings on Reddit, and Burlington Electric addressed them. (Schoppe acknowledged that his disclosure process was not ideal.)

Johnson said he "had a hell of a time getting Ernie to talk to me" about the issues he discovered with NEMRC's software, and that Saunders seemed "skeptical" of the problems during their only phone call, in 2018. Months later, Johnson noticed that NEMRC had released software patches to clients noting "security enhancements" in the product. A patch last July fixed the two local server issues, and another in December resolved the cloud backup vulnerability, simpleroute determined.

In its report, simpleroute states that the company decided to publicize the since-fixed issues to provide towns with "critical" cybersecurity information and to spur public debate about the security of the towns' systems.

Vermont requires companies to notify the Attorney General's Office whenever they discover data breaches, but the law does not extend notification requirements to the discovery of security vulnerabilities.

The state does, however, require businesses to take reasonable steps to protect customer data. In 2016, the Attorney General's Office entered into a legal agreement with software provider Entrinsik to put vendors on notice that they can be held responsible for vulnerabilities that their software introduces to its clients.

Assistant attorney general Ryan Kriger said the agency's consumer protection division is aware of the security problems identified in NEMRC software, but he would not say whether it's investigating them.

Carroll, of the Vermont League of Cities and Towns, declined to comment on NEMRC but said her organization hasn't received complaints from members about the newly disclosed software vulnerabilities.

Winooski City Manager Jessie Baker, whose municipality uses NEMRC for processing property tax payments, was not aware of the vulnerabilities when contacted Monday. Simpleroute's findings also came as a surprise to Tom Leitz, director of administration for the City of Saint Albans, which uses NEMRC for all of its business functions. After Seven Days provided Leitz a copy of the report, Leitz said his office would "need a little time to digest it with our consultant team and to assess if we have been breached."

It's unlikely, though, that they'll ever know for sure. Leitz noted that the city doesn't have the ability to discover or track potential breaches.

Experts say such limitations aren't unusual. Municipal governments, like small businesses, often lack the resources or expertise to monitor the security of their data systems. But they say it's important.

Simpleroute is one of a growing number of IT consultants that offer security audits to help protect sensitive data, though its current footprint in the municipal sector is small. That's not for lack of trying. Small-town administrators with modest budgets often have a hard time justifying the thousands of dollars it costs for the services, Johnson said.

He acknowledged that his company stood to gain new clientele if publicity surrounding its disclosure about NEMRC's software persuaded towns to purchase data security services or switch consultants.

Champlain College's Senator Leahy Center for Digital Investigation is hoping to remove financial barriers to data security by building an open-source monitoring system that could give nonprofit organizations "amazing security visibility into their networks," Rajewski said. The center's faculty and student employees are working with two local nonprofits, he said.

Saunders said he's been emphasizing general security practices with his clients since being alerted to the NEMRC bugs.

"A lot of the bigger issues lie with our clients themselves," he said. "I'm not trying to criticize our clients, but I'll go into some of our client offices, and the clerk will have the password taped to the computer.

"In Vermont we used to leave our doors unlocked at night. Now we can't anymore," he continued.

Despite his witch-hunt comparisons, Saunders said the flaws were still a wake-up call for his company and that simpleroute didn't overstate them in its report. "I would say that simpleroute did a good job exposing these to us, and we did a good job improving the software," he said.

The experience also convinced Saunders to start recommending that his hundreds of municipal clients hire consultants to provide security services for their networks.

His preferred partner? A simpleroute competitor, Williston-based DominionTech Computer Services.

"I wanted to rely on a company that understands our software," he said.

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.