- Matthew Thorsen

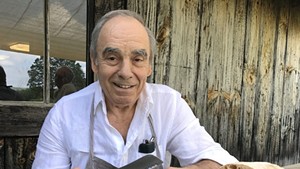

- Gérard Rubaud

In the past week, during his 12- to 14-hour days of making bread, Gérard Rubaud has noticed himself bending forward. It’s not much of a surprise that his body isn’t doing exactly what he’d like. In 2004, the 70-year-old Westford baker suffered a stroke that left him clinging to life for two weeks, then wheelchair bound.

Out of the wheelchair now, Rubaud still has a near-total lack of sensation on his right side. In recent days, he discovered he couldn’t independently grab the overhead lamp that he shines into the oven to watch his bread’s progress. “I had to take a hook to bring the lamp down, so I get really pissed,” he says with a scowl.

Yet he continues to press on. Gourmets will recognize Rubaud as the baker of Gérard’s Bread, which flies out of stores as soon as it’s delivered. Almost eight years after his stroke, Rubaud is back to producing 600 to 700 loaves over five days each week, with workdays that start at 9 p.m. and end the next afternoon. He gets help about half the time from apprentices, Rubaud says, but they don’t put in his long hours.

To keep up this punishing schedule — and satisfy his customers — Rubaud relies on another assistant: Uwe Mester, a certified practitioner of the Feldenkrais Method. Two years ago, Rubaud replaced his traditional physical therapy sessions with monthly at-home Feldenkrais lessons. A French native, Rubaud learned about the method in Europe. There, it’s better known and even covered by health insurance in many countries, says Mester, who immigrated to Vermont from Germany with his American wife in 2008.

Israeli physicist and engineer Moshe Feldenkrais invented the method, which uses physics and biomechanics to help connect the different components of a body’s movement: from the brain to the whole skeleton, then to the muscles, then back to the brain. Mester received instruction from Chava Shelhav, Feldenkrais’ former assistant.

Feldenkrais is considered an educational approach, not a medical one. “I don’t heal people,” says Mester. “What I do is to help people to understand how they are moving and alternatives to the way they move. That can really help them to overcome limitations in their movements.”

But there’s more to it, says Mester, struggling to explain the method without a hands-on demonstration. “It’s very based on experience. It’s like if you want to describe how something tastes and the person you’re talking to has only been to fast-food chains — they’ve never been to a very good restaurant — and you say, ‘Let’s try this food, and it’s very different from a hamburger,’” he says.

On a recent Friday, no burgers are on the menu when Mester arrives in the outer reaches of Westford for a session with Rubaud — pain levain, made from a mix of wheat, rye and spelt and leavened by wild yeast, is.

The baker complains that in the six hours he devotes to shaping loaves each workday, he notices the forward lean developing. “I practice the mistake, and I’m good at the mistake after a while. You polish your mistake,” he says.

To prevent the lean from crystallizing into a diamond, Rubaud says, he’s been stopping every 25 minutes to walk around, look up and try to straighten his upper body. “That’s pretty much because I’m convinced if I don’t do it, I’m limiting myself a great deal, and I’ll be shot,” he says. His inability to grasp the lamp hints at future trouble.

In the rustic, wood-paneled room that doubles as Rubaud’s bedroom, Mester starts his patient on a simple exercise he can do on his own later. He asks Rubaud to slowly and fluidly raise the toes of his left foot. The baker repeats the motion several times to ingrain it in his nervous system.

This is the basis of Feldenkrais. As neuroscientist Karl Pribram has said, “Feldenkrais is not just pushing muscles around, but changing things in the brain itself.” The method’s gentle movements build and rebuild the neuromuscular patterns that help a body cooperate with itself like a well-oiled machine.

It’s also about flexibility for both practitioner and patient. When Mester asks Rubaud to try lifting the toes on his right side, he balks. “Forget it,” he says. “The only way I can lift the front of the foot is if I’m seated. If I’m seated, I can lift a little bit.”

Mester allows Rubaud to sit down on the padded folding table that he brings to appointments. (He teaches four weekly group classes at Evolution Yoga in Burlington and Ten Stones Circle in Charlotte.)

Even sitting down, the baker isn’t able to do the movement on his own. So Mester moves the toes for him. The neural pathways are created whether or not the body itself is moving, he explains. And whether or not it’s conscious: Rubaud admits that he often falls asleep during their sessions.

He almost drifts off after Mester has him lie on his back and begins manipulating his arm, isolating each movement from back to shoulder. Every joint is carefully articulated, like those of a cartoon dancing skeleton. The result is a hyperawareness that not only relaxes those muscles and joints, says Mester, but often relieves pain.

The motion can even bring back feeling where there was none. After his very first session with Mester, Rubaud said he could feel his foot for the first time in six years. Now, with regular sessions, he says his awareness “flickers on and off like a light.”

Early on in his recovery, Rubaud, once a skier on the French national team, had hoped to hit the slopes again. More recently, he’s become less ambitious. “I am realistic now. I want to be able to work as long I can. I don’t want to be in a wheelchair anymore. I’ve had enough of this,” he says.

Rubaud says he’s not ready to stop baking, “because it’s a good pastime.” After a baking career that began at age 13, and 15 years in the loaf business, the beloved bread maker still considers his work a hobby. But it’s a hobby that’s helped him recover.

“To have a passion which gives you exercise at the same time, it helps,” Rubaud says. “You have the delivery person or employees who need the work and need the money. It’s a little bit of pressure to [keep the business going]. We’re all lazy by nature. It’s better to be forced.”

Mester goes on to perform the same shoulder movements on Rubaud’s right side. There, his body yields to Mester’s manipulations as if he were asleep, though Rubaud is actually recounting the story of an avalanche he survived in Val d’Isère, France, in 1966. When he was discovered, he says, his lower body had turned blue. “If I can get out of an avalanche, I can get out of this,” he says. “At least I was not dead. If I’m not dead, I’m alive, and if I’m alive, I can go back.”

Now, at 70, Rubaud has finally learned to slow down. He says that baking bread with more sense of purpose — like the deliberate motions Mester is now making with his legs — has yielded better loaves than ever. “[Slowing down] brings attention to what you’re doing,” he explains. “It’s like making one great bread instead of three mediocre. It’s better to choose your battle and be good at it.”

“He’s out for quality, not quantity,” Mester agrees. “It’s the same thing with Feldenkrais; we’re looking for quality of movement, not quantity.”

When Mester is done moving Rubaud’s legs, he helps him slowly rise to a seated position. The difference is dramatic. Rubaud says he’s still dizzy from sitting up, but the bent figure that lay down less than an hour before has been replaced by a modestly slouched one. Mester moves his student’s foot. “I sense very well,” says Rubaud. “Everything. It feels like the sandpaper between the vertebrae is gone.”

Then he lifts his right foot himself — a small but meaningful movement. “I can see the chain of command lifting through the foot,” Rubaud says, as his knee and hip move slightly, too.

It’s one of his two days off, but Rubaud wants to return to his oven — this time not to bake. It’s time to face his opponent, the oven lamp.

With the help of ski poles and the moral support of his bilingual black labs, Max and Jojo, the baker haltingly ventures down the hill to the bake shop. It’s a bread lover’s paradise, decorated with murals of wheat and dusted in a fine layer of flour, just like Rubaud’s crusty sourdough. The custom-made oven door depicts historical bakers at work. Above it looms the metal handle that will bring down the lamp.

Rubaud reaches for it. Now visibly straightened, he has the necessary extension, but can’t seem to locate the lamp. Then Mester makes the suggestion that makes all the difference. “Look up,” he instructs.

Brain damage sometimes prevents people from remembering the most basic things. Looking right at the lamp’s handle, Rubaud grabs it and raises it back in place. He pulls it down and back several times to ingrain the motion. The baker has won this round.

Despite this victory, Mester confides frankly that Rubaud isn’t on the road to a miracle cure. “Some of it will last, and some of it will be forgotten again.” he says. “For me, this first time is a critical one.”

For his part, Rubaud is excited by each small triumph. “I know I’m capable, because I believe the system is not broken,” he says. “The hope is critical to believe there are still major things I can work for. You know you’re not at a dead end.”

Far from it. He, and his dough, are on the rise.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.